Advertisement

Q&A: Trillion-Dollar Maryland Wisdom On Setting Hospital Prices

Bob Murray estimates that if the American health system had been run the way he has helped run Maryland’s over the last 25 years, the country could have saved close to two trillion dollars.

Did that get your attention? Now to get a bit more provincial: As Massachusetts heads into its next phase of health reform, there’s growing talk that price caps or other government restrictions on the ever-rising costs of health care are needed — at least temporarily.

What would that mean? Nobody knows at this point, but this seems like a good time to ask about a unique model for using state regulation to hold down health costs: Maryland. Its independent Health Services Cost Review Commission has been setting price levels for its hospitals since 1971. The Baltimore Sun's Jay Hancock wrote here on Sunday: "If the nation is ever to get insane health care costs under control, the methods used are likely to be tougher, stronger versions of what's going on in Maryland."

At the moment, Bob Murray is the ultimate short-timer. Friday is his last day, after more than 18 years as executive director of the commission, which sets all hospital prices, including Medicare and Medicaid, for both inpatient and outpatient services in Maryland. So before he leaves, we asked him to share his hard-won wisdom, particularly any that might be relevant to Massachusetts.

Q: First, Bob, in a total nutshell, how does it work in Maryland?

Quite simply, the Commission has the legal authority to set hospital payment levels for inpatient and outpatient services for all payers. Of course the system is much more nuanced than that but in a nutshell we are the only state (owing to the existence of a federal waiver) to do this for both commercial insurers and public programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Because we have this price setting authority, we can control both the growth in hospital prices and structure payment to induce hospitals to both control costs and help meet other policy goals.

Q: So over the years, how well has that worked?

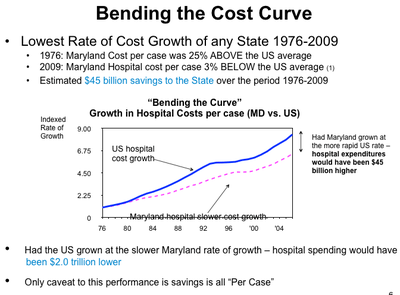

If you take a look at that chart (below) it shows we have the absolute lowest rate of growth of hospital cost per case of any state. And that if we had grown at the U.S. level there would have been $45 billion more in hospital expenditures. If the U.S. had grown at our level during this period, it could have saved nearly $2 trillion.

Q: So, loads of money has been saved but how have the hospitals reacted to this? Haven’t they protested non-stop?

Generally, as in any sort of major sports events, when you have a set of rules and a referee out in the field, people conform to the rules. It’s human behavior; particularly when you have broad regulatory authority to enforce the rules. It’s also our experience that at the end of the day most people are happy that there is a coherent structure in place and a set of rules they can operate within. But again, we are the referees. We aren’t out there doing the punt, pass and kicking – meaning we are careful not to micro-manage the hospitals.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]Most people believed the market was going to take care of cost containment. Clearly, it didn’t succeed.[/module]

The other important dynamic here is we don’t set these rules in a vacuum. The commission provides a forum for a cooperative rule-making process with input from the major stakeholders. We get together and negotiate things out with hospitals and payers. This is also all done in a public setting which adds to the overall transparency. And it makes the whole process more acceptable because people’s voices are being heard.

Q: So if it’s so great, why is nobody else doing it?

A variety of reasons. There were some unique things in Maryland that got it off the ground in a positive way. Maryland tends to opt more for a regulatory approach, given that it has traditionally been more of a Democratic state. By contrast the U.S. has been schizophrenic about regulatory vs. market solutions to cost containment. Back in the ‘90s the US made an overt decision to move toward market-based solutions given the dominance of managed care. Most people believed the market was going to take care of cost containment. Clearly, it didn’t succeed.

Prior to this, there were a few states (New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Washington State) that tried rate setting. I think their lack of success had to do primarily with the regulatory approach they adopted. These states didn’t build the political coalition necessary to make rate-setting a success but they did build all the excruciating rate-setting details into their statute and regulation. Both dynamics cut down on the flexibility of their systems. By contrast the Maryland legislature gave the Commission the considerable flexibility to evolve and modify our system over time.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]

Certainly that takes a big leap of faith by a state legislature. But we’re about to leap into oblivion with regard to health care costs, so maybe it’s time to take that leap of faith.

[/module]

In Maryland, our statute included only the economic principles and policy goals. It also gave us a great deal of political, legal and budgetary independence. This flexibility and independence laid the groundwork, and then the Maryland legislature said to the Commission “The rest is up to you - design the system to achieve our goals.” Since that time we have used this latitude and political insulation to craft rate methods that reward hospitals for behavior that helps us attain our policy goals of cost containment, expanded access, payment equity, financial stability and better quality.

Q: So doesn’t that mean, though, that so much depends on the political specifics of a state? And if a state has a more problematic political environment than Maryland’s it might not work?

I don’t know. I think it can work if a state or the federal government creates an independent enough structure and walls it off budgetarily, politically and legally to let the commission operate in the public interest. Certainly that takes a big leap of faith by a state legislature. But we’re about to leap into oblivion with regard to health care costs, so maybe it’s time to take that leap of faith.

Q: Do you see other states at this juncture heading more in Maryland’s direction, ready to take that leap of faith?

Certainly the Accountable Care Act had a provision in there that almost was encouraging states to look at all-payer regulatory approaches. Vermont has passed legislation to do what they call a single-payer system but that in reality has many elements similar to our system. I think it’s going to be more of the same states that tried it to begin with, those in the northeast and northwest: Washington State, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts.

Q: So basically it’s just that the health care cost crisis is getting so bad that people are becoming more willing to reconsider regulation?

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]The imbalance in many markets has grown to absurd levels.[/module]

Yes, and I think it’s because the market-based solutions haven’t worked largely because of what economists call “market failure.” Most recently, the principal threat is the lack of purchasing power by payers — but more importantly, by the people they represent: businesses, labor, families, taxpayers, individuals. The imbalance in many markets has grown to absurd levels.

Q: Are you familiar with the Massachusetts market at all? Are there any specifics of it that would lead you to expect one direction or another here?

I’m not familiar with all the dynamics of the Massachusetts market but I know that the Boston area is highly concentrated with Partners HealthCare and with the academic centers. I’ve seen some data that showed the Boston market as being quite high. There are other examples of that too — San Francisco, areas of Florida, Pittsburgh. There are some very dominant health systems out there. And basically the dynamic in these and many other markets is that providers have such market leverage, they can negotiate higher payment levels from private insurers. And if insurers don’t come to the table, these system sit back and capture a large portion of an insurer’s patients out of network through their emergency rooms, where the insurer is forced to pay even higher prices. It is becoming a completely dysfunctional situation, not to mention unaffordable.

Q: So what I wonder is, how in the world could we ever get from that to a system in which providers like Partners are told by the state how much they can charge?

Well, back in 1974, the disparities were not as dramatic as they are now, but that’s basically the heavy lifting the commission had to do. We had to collect a lot of data, and analyze the data to be able to say what’s reasonable and what’s not reasonable and then start to set some limits. Certainly it wasn’t an easy thing to do, but it can be done.

And now the alternative is far more draconian, which is we’re going to have massive disruption, in terms of payment cuts and payment disparities. Medicare payments are going south and that’s probably true of Medicaid as well, and the private sector payments are going north, and those growing disparities will cause access difficulties. People increasingly won’t want to accept Medicaid and maybe Medicare. And in the meantime providers are pricing the private sector out of the market. So I think the alternative is far worse, given the large disparities and the massive payment cuts that will have to occur.

Q: I’d imagine the Maryland equivalent of Partners — or rather, of the Harvard Medical School-affiliated hospitals here — is Johns Hopkins, a giant in health prestige and today once again rated tops in the nation. How did you deal with them? Did they not complain that for them to accomplish their important missions, including teaching, they needed to be paid a whole lot?

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]As hokey as it sounds we try to do what’s in the best interest of the public.[/module]

I think the quid pro quo for establishing reasonable cost limits is to support laudable missions of hospitals, and those are expanding access to the uninsured, financing care for the uninsured and also supporting their teaching and research missions, and otherwise providing a stable financial environment, which our system does. Accordingly, the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins strongly support the rate system.

Q: They don’t say they’ve been hurt by it?

A: We do meet with the academic centers frequently and they often say they are disadvantaged for this reason and that reason. So we do make ourselves accessible to try to cut through it all. Where they have legitimate arguments we look to support them, yes.

But as I said it is a quid pro quo they accept - of setting limits on cost growth but at the same time gaining support for traditional missions that are in the public interest as well. And that’s really our mission: as hokey as it sounds we try to do what’s in the best interest of the public.

Q: So do you have any advice for Massachusetts?

You’ll have to collect data to be able to make those determinations of what’s justified and what’s not. It’s not just cost data but quality data because that’s an important part of this evaluation: the value of the dollar expended. Things need to be transparent and you need these data to measure performance in a fair way. So I think that would be the first step.

But then ultimately there will have to be limits. I wouldn’t advocate a very complex and structured system like we have here, that has become highly technical and detailed. It has to be a gradual process, guided by an independent agency, toward rationalizing or restricting the level of pricing — because prices are too high in the private sector — and reconfiguring the structure of pricing. By structure, I mean moving the system away from a fee-for-service — the more you do the more you get — type of payment, to what people talk about as global payment or bundled payment, which Maryland is also currently having a lot of success with.

Q: So now that you’re leaving, what can you say publicly that you could not have said before? I imagine that your 18 years have been packed with just incredible conflicts that eternally needed ironing out?

Yes, absolutely. I’m just going to repeat myself: We take some satisfaction I guess in playing the role of referee that can step in, that doesn’t have a political interest or doesn’t represent a special interest; to try to sort things out and figure out what’s in the best interest of the public. And we do that at various levels: incredibly detailed issues, middle-level issues and very macro policy issues. Everyone has a self-interest and that’s what makes this country great and the marketplace great. But you want to have some type of mechanism that makes this all work toward some common goals and steer those forces in that direction so that at the end of the day the public is better off.

That’s been our general philosophy that we’ve applied, and we’re small enough to be able to do that, and exercise judgment, and then try to be as fair as we possibly can.

Government has a role to try to create standards and uniformity and act as a referee. That’s one of my main messages. And particularly, now, to act as this countervailing force to market power.

Right now, in any given region, hospitals can act as natural monopolies, as “price setters.” That’s an anti-competitive dynamic. People say, ‘Oh, we’ll let the market work.’ Well, it doesn’t work. Let’s be practical about this. Given this dynamic there is a role for government, to push back, to be that countervailing force for the time being. But at the same time structure the system to be flexible enough to allow competition to work when it produces more effective results. We can’t think that government is always successful. There’s regulatory failure, too. Government moves slowly, sometimes, and is rigid. We’ve got to build a system that’s flexible and operates at that macro level and embodies the best of both approaches.

And I’d also emphasize the political independence: Try to wall off this entity as much as you possibly can. They can’t be in their own little world, they have to evolve with changes in the market and be able to respond to inquiries, but to insulate them from political pressure is very important. And then that idea of a forum for discussion and cooperative rule-making is very important. So people feel they have their voices heard.

Q: In Massachusetts, there’s a great deal of fear that health care reform, in its coming phase, could somehow hurt the industry that at this point accounts for 1 in every 7 jobs statewide. And certainly, when people talk about increasing regulation of health care, those fears get fanned. How would you respond?

A; I default to that draconian alternative. Economists say that for every job we add in the health care industry, we give up 1.3 jobs in the rest of the economy, because health care costs go up and erode real wages, and people drop employees. So it’s not a growth strategy. We have to be mindful of that.

Plus, there is substantial evidence from Maryland and MedPAC — they are the independent commission that advises Congress on Medicare payment policy — that there are some 700-800 hospitals nationally that face very strong pressure from private payers, meaning the private payers are dominant, and then they get fixed payments from Medicare, and those hospitals have the lowest actual costs in the nation. So there’s evidence to show that we can all do a better job.

Hospitals in the highly concentrated markets that can shift their costs or prices don’t manage their costs well. It’s just human behavior. And we don’t seem to be getting better value for this higher cost either.

So my conclusion is: We have to do it differently: A) our current course is not sustainable and B) it’s demonstrably achievable that hospitals, when given the right set of incentives, can manage their costs more effectively. The stakes are pretty big here, financially and in terms of public welfare. And there is no palatable alternative.

Readers, thoughts???

This program aired on July 20, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.