Advertisement

60 Years Of The Modern N.H. Primary

Resume

Over 600 reporters were in the press room for last Saturday night's Republican primary debate. That's an avalanche compared how many came here when the modern New Hampshire primary started in 1952.

It's preposterous, of course, to think that New Hampshire, the first in the nation, is actually representative of the nation. It's as preposterous as thinking that made-in-New Hampshire-Moxie is the national soda. And it's not even what it used to be, either. But if you don't look too closely at the thing, it's still a great show.

"Everyone is in there pitching in an endeavor to gauge the mood of the American people," said one journalist from an old newsreel.

Invented in 1913, the primary had little bearing on the nation until it went to direct voting in 1952 when this newsreel set the mold of the thing:

The citizens of the Granite State are not easily won.

In fact, they set a pattern by rejecting the sitting President Harry Truman in favor of Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver, who wore a coonskin cap while riding a snowmobile. In reaction, Truman decided not to seek reelection.

"What we start here in New Hampshire today I believe must succeed next summer and next November," said John F. Kennedy in file audio of him speaking in New Hampshire.

John Kennedy may have been the first, but he wasn't the last to suggest New Hampshire was the birthplace for Saviors.

The first campaign to call itself a crusade began here in 1968.

"We raise the issue of the war," said Sen. Gene McCarthy of Vietnam. The anti-war poet declared, "there comes a time when an honorable man simply has to raise the flag."

And New Hampshire saluted.

"Dover: McCarthy, 47, Johnson, 44. McCarthy, 205, Johnson, 197," said the news reporter, reading the results as the votes rolled in.

President Johnson won New Hampshire, but in another phenomenon that became a tradition here, in winning he became the loser because he failed to meet the expectations of a big victory. Johnson's initial response was right on target.

"You know, the New Hampshire primaries are unique in politics: they are the only races where anyone can run and everybody can win," he said.

But soon enough, Johnson announced he wouldn't seek reelection, and the New Hampshire primary was legend.

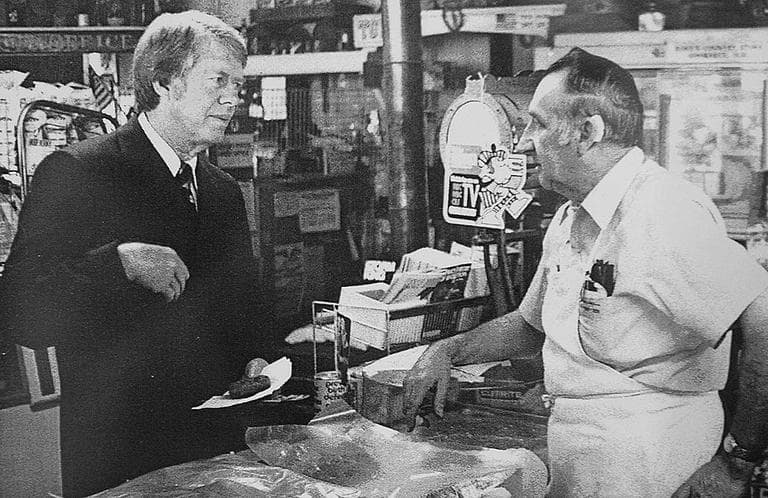

Eight years later, that legend grew with the victory of a largely unknown governor of Georgia. Former Boston Globe reporter Curtis Wilkie witnessed the rise of Jimmy Carter.

"I covered this guy that kind of came out of obscurity and really got his start in New Hampshire in '76," Wilkie said.

"Stayed at people's houses as I recall," I said to Wilkie.

"Oh yeah, and he carried his own bag," he replied.

But in the New Hampshire primaries of yore, there were no more than three networks, no cable, maybe 50 political reporters, and only a handful of primaries across the country.

"There were only two or three of us covering Carter. You got to ride around with Carter in the car, not on the press bus. He didn't have a press bus," Wilkie said.

By the '80s it was getting complicated, more theatrical, more media-driven, as witnessed Ronald Reagan demonstrating how tough he would be with the Soviets while engaged in an argument about who would participate in a candidate's forum.

"Would the sound man turn Mr. Reagan's microphone off."

"I am paying for this microphone, Mr. Green," Reagan said."

By the 1990s, the New Hampshire primary had become a media circus. It even had its Elvis, aka Bill Clinton. And the issue, new to New Hampshire, of what one Clinton staffer called "bimbo eruptions."

"Who is Jennifer Flowers? You know her? How do you know her? How would you describe your relationship?" a "60 Minutes" reporter asked Clinton during an interview.

Sex-capades, "60 Minutes," and the screaming hounds of the press were at the candidate's heels, and so too another challenge:

I did not dodge the draft. I did not do anything wrong.

To this high drama, Clinton made an impromptu impassioned speech a few days before the primary, asking New Hampshire for a second chance.

"And he said, 'If you do I'll be with you 'til the last dog dies,'" Wilkie said.

Clinton came in second and sounding like he won.

"New Hampshire tonight has made Bill Clinton the comeback kid," Clinton said to applause.

Equally exciting was the second ring of that circus in 1992, involving Pat Buchanan, who took on the first President Bush.

No candidate ever seemed to enjoy himself more than the locked and loaded verbal tommy gun taking on the Republican establishment.

"They hear the shouts of peasants from over the hill. You watch the establishment, all of the knights and barons will be riding into the castle pulling up the drawbridge in a minute. Because they're coming, all the peasants are coming with pitchforks after them," Buchanan said to a laughing audience.

Bush may have won more votes but in the style of Johnson, he was the loser for not winning bigger. In 1996, Buchanan came back to urge voters to mount up and ride to the sound of the guns. This time he won the primary and lost the nomination. New Hampshire was losing its reputation of picking the ultimate winners.

By 2008 the candidates came with their own music, pitching to myths of New Hampshire. And to keep the franchise first in the nation, New Hampshire had moved the primary from the frost heaves of late winter almost to Christmas, but with less of the retailing that had made it uniquely New Hampshire.

"When they asked, 'How you gonna do it, you're down in the polls, you don't have the money,' I answered, 'I'm going to New Hampshire and I'm going to tell people the truth."

John McCain and Hillary Clinton even packaged the myth to make New Hampshire the New York, New York of races. If you can make it here, you can make it anywhere.

"I want especially to thank New Hampshire. Over the last week I listened to you and in the process I found my own voice," Clinton said to cheers.

Which brings us to back to what still makes the show interesting, as when the frontrunner falls: take Barack Obama in 2008.

"Yes we can to justice and equality," Obama said to a crowd cheering, "Yes we can, Yes we can."

For all of its distance from the pure, picture book primary of old, New Hampshire still relishes its ability to say "No, you can't."