Advertisement

How Your Kidneys Could Signal Trouble Ahead For Your Brain

The last time Dr. Julie Lin went for her annual check-up, she asked for tests of her kidney function that her primary care doctor would not otherwise have ordered.

It was not just that Dr. Lin is a Brigham and Women's Hospital nephrologist — a kidney specialist — and often sees patients who, by the time their disease has been detected and they have been referred to her, are verging on total kidney failure.

It was that she had found in her own research — which is just out in a leading nephrology journal — that tests of your kidney function can apparently yield surprisingly telltale insights into the health of your brain, and possibly other organs as well.

The research looked at more than 1700 women over age 70 in the long-running Nurses' Health Study, following them for up to six years. It found that in women whose urine tests indicated the very beginnings of kidney dysfunction, their cognitive abilities — higher-order brain functions like memory and verbal fluency — declined two to seven times faster than normal.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]

More than half a million Americans are in 'end-stage' kidney disease, and among them, 88,000 die each year.

[/module]

The cognitive experts working on the study were "really struck by how strong an association there was, how much faster a decline this very small amount of protein in the urine is signaling," Dr. Lin said.

The study mainly raises the possibility of an easy, non-invasive urine screening test that could provide a useful window into brain health. But it also has potential implications for a medical-emotional conundrum: Over 20 million Americans are afflicted by chronic kidney disease; more than half a million are in its ominous "end stage," and among them, 88,000 die each year. So why, oh why, don't you care more about your kidneys?

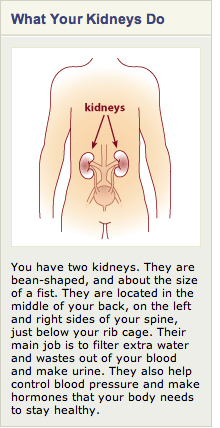

But first, a word of explanation. How might it work that our kidneys — whose main tasks include filtering our blood and regulating our fluid volumes — are apparently so good at raising red flags for an organ with completely different functions a couple of feet away?

The leading hypothesis, Dr. Lin says, is that our kidneys are exceptionally "vascular" — full of small blood vessels — and vascular disease in the brain is believed to be a major cause of cognitive decline. So a signal of vascular trouble from the kidneys could naturally speak volumes about the early signs of disease in the blood vessels nourishing the brain.

There's another possible element, she said: Inflammation. Albuminuria — the presence of a key protein called albumin in the urine, which was the marker measured in Dr. Lin's study — has been linked with inflammation, including vascular inflammation.

Dr. Daniel Weiner, a Tufts nephrologist and assistant professor of medicine, concurs that the study suggests that "albuminuria, at least in very, very small amounts, is probably a marker of small-blood-vessel damage throughout the body."

"The nice thing about albuminuria is that it’s very easy to measure," he said. And previous studies have demonstrated its significance at higher levels, linking it with increased rates of death and heart attacks.

It remains to be seen, Dr. Weiner said, whether the study by Dr. Lin's team should translate into broader screening for albuminuria and more intensive treatment for patients who have very low levels of it.

A major federal study now getting under way called SPRINT could yield some answers in several years, he said, at least about whether patients with very low levels of albuminuria should be treated more intensively for high blood pressure. For now, it is too early for the new cognitive-decline findings to translate into any action by patients or doctors, he said.

But might it, perhaps — and I'm stretching here, I admit — have some effect on the indifference or incomprehension that kidney disease seems to engender in some patients and in the general public? If we know the illness affects not just our obscure kidneys but our brains, where we live?

I've never heard of any other disease that prompts such a chorus from doctors of, "I tell my patients they have it but they just don't care!"

'Kidney disease, yada yada yada yada.'

Even the venerable Jane Brody of The New York Times wrote about the kidney disease communication problem:

A patient with early-stage kidney disease provided a recent wake-up call for Dr. Joseph Vassalotti, a leading kidney specialist. After explaining the diagnosis in great detail, the doctor asked his patient to repeat what he had heard in his own words.

With a rather bored look on his face, the man said, “Kidney disease, yada yada yada yada.”

I asked Karen Ryals, executive director of the American Association of Kidney Patients, whether the crux of the problem is that kidney disease tends to have no symptoms until it is very far along.

More broadly, she said, "People just don't realize how important their kidneys are." And because kidney disease tends to be caused by other illnesses — high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity — those other diseases tend to get much more attention. "Oftentimes people will die of those diseases, and the kidney is really more secondary," she said.

Research also shows that primary care doctors sometimes don't recognize kidney disease early enough; and they report trouble communicating the problem to their patients, she said.

"But let’s temper that with reality," she continued. "And the reality is that oftentimes I talk to internists and primary care doctors who say, 'We did say something to the patient, but they chose not to get tested, or take the time off work, or they didn’t have an insurance program. There are a lot of things in the world today, particularly in the working poor population, that prevent them from getting medical care."

"The other things that can happen, too — we know from patients we support — is that truly, it's a communication issue. So many patients tell us, 'I didn't really understand what my doctor told me, but I didn't want to ask questions. I was afraid. Who am I to question him or her?' And there are so many people who are functionally illiterate — reading at the fourth or sixth grade level — so I think it's a conglomeration of a lot of things. It's not that people don't care — it's that they just don't get it."

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'It's not that people don't care — it's that they just don't get it.'[/module]

Some people are young and feel invincible, she said. Others simply don't know what to do. "There's just a million different reasons why people don't follow up. Some people stick their heads in the sand. We've had people call here and ask, 'Should I just drink more water?' Or they'll talk to family members for advice."

The association tries to educate people and help them become their own health care advocates, she said. "We all know about blood pressure, why can't we know about GFR [a measure of kidney function] and your protein level in your urine? Especially if you have high blood pressure or diabetes, you darned well better."

Other kidney-disease basics that we had all "darned well better" know:

Who's at higher risk: According to the National Kidney Foundation, risk factors for chronic kidney disease include:

•diabetes

•high blood pressure

•heart or blood vessel problems

•a family history of chronic kidney disease

•older age (65 and older).

CKD is also more common in African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian or Pacific Islanders and American Indians.

What to do: The federal National Kidney Disease Education Program has easy-to-read pages here about testing, keeping your kidneys healthy, talking to your doctor and talking to your family. In brief: Controlling diabetes, high blood pressure and other factors in kidney disease can go far. Jane Brody includes a to-do list at the bottom of her Times story here.

The numbers: The federal statistics, including the price-tag: $39 billion a year in public and private payments. 88,000 deaths a year in end-stage patients.

This program aired on January 20, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.