Advertisement

Downward-Facing Docs: Med Students Study Yoga To Help Patients, Selves

Ben Tannenbaum, a wiry first-year medical student, is under pressure.

His typical day involves about five hours of lectures and test prep — physiology, genetics and histology on a recent weekday; a mad dash off to a clinic to practice as a doctor learning physical exams and basic medical history-taking; and then, after getting home around 8:30 pm, a few more hours of work reviewing the day's material before it all starts again the next morning.

"And that isn't including elective courses, student organizations, research, volunteer work, or extracurricular activities that almost everyone is trying to find time for as well," says Tannenbaum, a-24-year-old student at Boston University School of Medicine.

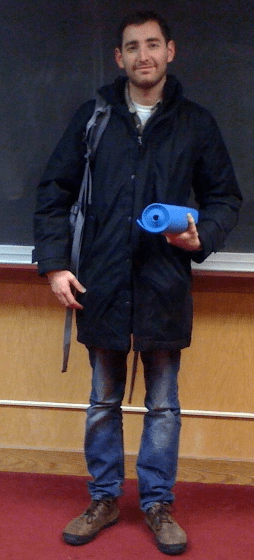

But on Tuesday night, the perpetual motion of Tannenbaum's life stopped. He entered a packed classroom, rolled out his blue yoga mat and plopped down on the floor. Alongside 25 other barefoot medical students, Tannenbaum listened to a half-hour talk on "the relaxation response" and how the technique — a simple type of meditation that reduces the activity of the autonomic nervous system — can alleviate stress-related maladies, from migraines to depression.

Then everyone took a deep breath and stretched into downward-facing dog. The yoga part of the medical school's weekly yoga course had begun.

As everyone knows, medical students are a singularly stressed-out lot. "More than 20 percent end up with depression, more than half suffer from burnout, and in any given year, as many as 11 percent contemplate suicide," Dr. Pauline Chen writes in a New York Times report on the "toxic" nature of the medical education process.

So it makes sense to offer these overwhelmed kids de-stressors like yoga and meditation. But here, at the BU medical school's first-ever yoga elective the aim is even broader: The faculty and instructors who launched the class hope these future doctors will be able to exploit their knowledge of yoga and its research-based benefits to someday help patients and to feel as comfortable prescribing yoga as they do Prozac.

"I'm leaning toward primary care," said Tannenbaum, the med student, speaking after class. "And it's so important to acknowledge that there are many paths to health and wellness. It's one thing to sort of know about yoga and other alternatives to pills and medications, but with the lecture component here, to really understand how it works and be able to talk about it with patients, I think that will be be very helpful."

So in these weekly, hour-and-forty-five minute classes, lead instructor Heather Mason — who designed the course — and members of the BU faculty introduce students to the research behind various elements of yoga.

The focus is mainly neuroscience, but there's also psychology, mind-body medicine, anatomy, and beyond. The class syllabus includes clinical studies on how the nervous system benefits through an elongated exhale, the mechanics of neuroplasticity, increasing heart-rate variability and alleviating lower back pain through postures.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]At Harvard Medical School in 1988, a yoga class that included lectures on neuroscience would have been "untenable, a total nonstarter."[/module]

"The unique thing about this class is that the students are getting this extra neuroscience component, so it's more than just experiential," says Dr. Rob Saper, the Director of Integrative Medicine at BU School of Medicine, who envisioned the course with Mason after the two met at a yoga research conference in India last year. Saper adds: "In 1988 At Harvard Medical School [where he was a student] a yoga class that included lectures on neuroscience would have been untenable, a total nonstarter."

In fact, Saper, as a burnt-out medical student, took a year off to study at Kripalu, the yoga retreat in western, Mass. which, he says, inspired him to "try to change medical education and medical care in a way that's more wholistic" and to make self-care a priority. "To the degree a medical student or health care professional can promote their own wellness — whether it's yoga, running, whatever — that person will be better able to provide outstanding health care and avoid burnout, which has been shown to negatively impact medical care."

It's worth noting that under the fluorescent lights here at the BU yoga class there are no fashionable Lululemon outfits nor orders to "push to your edge" with complex, increasingly controversial, poses.

Indeed, in Tuesday's class Mason, complained that she had no blocks to use for props; when there was a shortage of mats, some students were clearly unsettled by the prospect of practicing on the maroon-colored carpet badly in need of a shampoo.

"Who is familiar with the relaxation response?" asked Mason, who is also finishing up a master's degree in neuroscience, at the start of her lecture. One young woman raises her hand. The others shook their heads. "Well, if you want to use this in your clinical practice, you can teach someone in an hour and it can have a huge impact," Mason said.

Student wellness and self-care programs aren't new. Increasingly, they're sprouting up at medical schools across the country, says Dr. Benjamin Kligler, Vice Chair and Research Director of Beth Israel Medical Center's Department of Integrative Medicine in New York. But the shift has truly started to take hold in recent years: Kligler cites the rapid growth of the Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine (he chairs the group) which started with eight medical school in the late 1990s and now has over 50.

"Many of these schools incorporate into their curriculum an experiential approach, in which students actually participate in some type of "alternative" therapy — yoga, meditation, acupuncture for example — and then also learn about the evidence for and against effectiveness for these therapies as well as the clinical situations in which they tend to be used," Kligler says. But naysayers remain. "There are still conservative pockets out there," Kligler says. "People who feel there isn't enough evidence yet for us to incorporate some of these alternative practices into the medical school curriculum. But one counter argument is, if patients are doing it, it's something doctors should know about."

Indeed, with an estimated 20 million Americans doing yoga, it makes sense for doctors to at least have some understanding of what all the buzz is about.

Dr. Chris Streeter, an Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology at BU School of Medicine practices yoga and conducts research on its effects. She recently gave a Power Point presentation to the BU yoga students on how yoga impacts levels of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), a key neurotransmitter in the brain.

Streeter's latest research, published in The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine in 2010, and done in collaboration with doctors at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. compared two groups of exercisers: people doing yoga and people walking. The bottom line findings: After 12-weeks, the folks in the yoga group showed greater improvements in their mood and anxiety levels compared to the walkers, and there was a positive correlation between increased GABA levels, measured through brain imaging, and improved mood.

At the end of Tuesday's class — a series of sun salutations, warriors and pigeons — Mason turned out all the lights and led students through a short meditation. She had them relax various body parts and then repeat a simple, calming word with each inhale and exhale for about 10 minutes.

As Carolyn Smith-Lin, another first year medical student, packed up to leave, she explained the main reason she started attending the class: "It's good for my own mental health." But now, she says: "I can see how it could be part of an evidence-based practice." She's even started prescribing it, albeit informally: "I'm encouraging my mother to do yoga or tai chi," she says, "for the health benefits."

This program aired on February 10, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.