Advertisement

Birth Control Pioneer Says Fight Had Personal Cost

Taunts of "baby killer" and "butcher" still echo in Bill Baird's ears, nearly five decades after he began fighting for birth control and abortion rights.

Now 79, the Massachusetts man says a Georgetown University law student's recent verbal bashing on a national radio show is evidence that rights he equates with liberty and equality are in jeopardy.

"There will always be those who will try to deny us our freedoms," Baird wrote in a letter to student Sandra Fluke, who testified to Congress about birth control. "As you have seen, it takes eternal vigilance to fight against those forces."

Baird's own fight started grabbing headlines around April 1967, when vice squad cops arrested him for showing contraceptive devices to 2,500 students at Boston University.

He left the lecture that day in handcuffs, an arrest he spoke about last week as he marked the 45th anniversary of the event.

Baird told about a dozen Democrats inside a stately home across the Charles River how Boston police helped advance his plan that day.

How his arrest for giving spermicidal foam to an unmarried 19-year-old coed set up a constitutional challenge that propelled his case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which resulted in the court's decision that gave unmarried people the same rights to birth control as married people.

But he also described how that ruling, and others since, came at a personal price.

Decades of activism for birth control and abortion rights cost him a marriage, and the trust of most of his children, Baird said. It also left him with barely enough income to get by.

The lecturer who once netted $3,000 a speech said he poured the money into court cases, and running clinics that gave abortions to poor women.

Baird said he dodged bullets. Survived a firebombing at one of his suburban New York abortion clinics. Endured death threats along the way.

"My mail runs a hundred to one: people praying for my death," he said.

Baird told the audience he believes opposing political and religious forces are threatening the causes of privacy and freedom he's championed.

In 1979, his name was on a different Supreme Court decision that gave minors the right to abortions without parental consent.

But as a recent cancer survivor, Baird said he also thinks about his mortality. He said he fears that when he's gone, his life's work will be forgotten.

"I say tonight, `Will you help me?' `Will you write a letter?' `Will you get me a speaking engagement?"'

---

Baird says some people also have called him the devil because of his pro-abortion work.

His crusade started in 1963, when a woman who tried to give herself an abortion with a coat hanger died in his arms in a New York City hospital. He was clinical director for a contraception company at the time.

Baird says he opened the country's first abortion counseling center a year later. The facility on Long Island, N.Y., referred women to physicians who would perform then-illegal abortions. In decades that followed, Baird operated two clinics on Long Island and another in Boston where women could go for legal abortions.

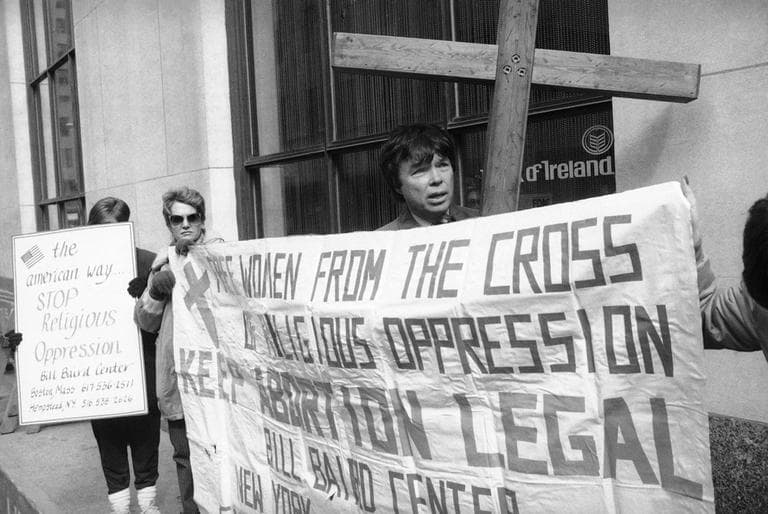

He often pitted himself against Catholic Church leaders who preached an anti-abortion message.

In 1979, he sued to try to stop a public church service by Pope John Paul II in Boston. In 1985, a Catholic bishop led 3,000 people in a protest at one of Baird's New York clinics.

Baird also claims some feminists and pro-abortion rights forces have tried to discredit him or downplay his contributions.

"There were very few men who came out and championed the women's movement," Joyce Berkman, a history professor at University of Massachusetts Amherst, said last week. "And to have him champion their sexuality was suspicious."

In 2008, some of Berkman's students put on an original theater production based on Baird's activism.

"Bill is a real crusader and you need those people," Berkman said. "No movement succeeds unless you have a militant group within it."

Baird totes around a portfolio of old press clippings, meant to convince listeners that the things he talks about really happened. He talks frequently of his arrests in five states. He also likes to display a copy of a pamphlet he says shows that unlike him, Planned Parenthood opposed abortion in the early 1960s.

But both supporters and opponents say Baird already has a place in history.

The Rev. Frank Pavone, the Catholic priest who heads the anti-abortion organization Priests for Life, said he respects Baird as a "warrior."

Pavone said the two became friends after years of meeting at Right to Life conventions, where Baird pickets each year. In the past, the two men released a joint statement asking their supporters to avoid inflaming the other side with rhetoric.

"Many people who come to know him well draw strength from his fighting spirit," Pavone said. "... If you can break the law peacefully to advance a cause, both he and I believe in that."

Officials from Planned Parenthood Federation of America in New York declined an interview about Baird last week, but said in a statement that his 1972 Supreme Court win was "a cultural landmark that has impacted generations of Americans."

Massachusetts lawyer Thomas Eisenstadt called Baird a "trailblazer." He is the man whose name is on the other side of the 1972 decision, Eisenstadt vs. Baird, that gave unmarried people the right to birth control.

Then sheriff of Suffolk County, Eisenstadt was Baird's jailer when the activist spent 36 days in Boston's old Charles Street Jail after the conviction that followed his Boston University arrest.

"That was preposterous, those old, arcane laws," Eisenstadt said of the case. "I think it's made a tremendous impact on society."

The former sheriff also said Baird had a knack for attracting publicity.

"As he was leaving the jail he said: 'Stick with me sheriff. You'll get a lot of TV coverage.'"

---

A couple of hours before his Cambridge lecture last week, Baird went back to the old Charles Street Jail.

Squalid conditions led a judge to order the facility to close in 1973. It reopened as a luxury hotel in 2007.

Baird said his memories of rats and lice, of a blood-stained mattress, of screams echoing among the granite cells, still unnerve him.

While at the hotel, Baird studied an exhibit with his photo that describes him as one of the old jail's notable prisoners. Then he posed for photos by the bars of an old cell, when a stranger who walked by tried to joke with him.

Before Baird quipped he'd actually once been an inmate.

"Wow," the man said then, "There's a prisoner here."

Later, Baird's words left an impression with the clot of Democrats who listened to him speak for more than an hour.

"He's so right ... We forget history and what people like Mr. Baird have accomplished," Cambridge resident John Roughan said.

But Baird is determined to make sure people remember, so what he fought for isn't lost.

"I have no money. I have no political power," Baird told his audience. "But I will never surrender. I will never give up. I believe that women and women alone must be free to make these choices."

There were no handcuffs this time when his lecture ended.

This program aired on April 9, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.