Advertisement

Celebrating The Paper Clip: MIT Pays Homage To Humble Heroes Of Design

This story is about some of the objects we use every day. Not the "rock star," high-tech devices — like smartphones or laptops — but the more low-key tools that hold our papers together, keep our pants on, or help us open our bottles of wine.

These underdogs of design are being celebrated in a new exhibition at the MIT Museum called "Hidden Heroes: The Genius of Everyday Things."

The lowly hammer could’ve been included in this exhibition, but instead the installation team was putting it to good use the day I visited the MIT Museum. They were assembling 36 large, diorama-style boxes to display 36 classic objects.

MIT curator Gary Van Zante sees the exhibition as a much-deserved tribute to our most humble tools.

"One way to look at it is as a history of invention," he explained. "These are practical problem solving ideas that have come about over the centuries. It’s things we overlook every day, like the paper clip."

Van Zante calls the paper clip a "minimalist masterpiece" and an example of "design with a small 'D.' " Very different than so many of the modern things we use and wear these days.

"We like to know the designer, we even wear designer’s names, but these are, in our mind, mostly anonymous objects," Van Zante said. "For most people they’re not going to know the name of the inventor of the paper clip, so it’s a different angle on design."

Samuel B. Fay won the first U.S. patent for a bent wire paper clip in 1867, but other inventors dreamed up similar ideas in Britain and Germany. The Norwegian paper clip, patented by Johan Valler in 1899 and 1901, gained mythical status because of the role it played in World War II.

"Norwegians wore a paper clip as a coded symbol of resistance to the occupying Nazis," Van Zante told me. "So we go from a simple tool to a symbol of nationalism."

And that’s just one of the stories behind this collection of objects and their makers.

The Rev. Samuel Henshall, of Oxford, patented the first direct pull corkscrew in 1795. Today, 50,000 types are on the market.

There’s also the canning jar, Post-its, pacifiers, bubble wrap, coffee filters and the tea bag. Van Zante says each and every item meets a few critical criteria.

"Longevity, cheapness, durability, sustainability, the perfect balance of form and function. They stay with us because they do their job," the architecture and design curator said. "They serve their practical purpose."

Documentary footage is projected inside some of the dioramas, showing how these objects are made. In one, a woman describes how dry condoms are stripped from glass holders to be washed in the factory. There are also posters from a successful British ad campaign devised to prevent the spread of AIDS. Cucumbers, carrots and a few other veggies fill the stretchy contraceptives.

Do you know who’s credited with inventing the first rubber condom? It was Charles Goodyear, the first rubber manufacturer, who patented the first rubber condom in 1844.

"Many of these are actually much older than we think," Van Sante said while considering the condom's origin. "Yet they are as useful today as they ever were."

For instance: the tin can. Napolean inspired the metallic vessel's birth by asking his troops to come up with a smarter, air-tight food container for their perishable goods.

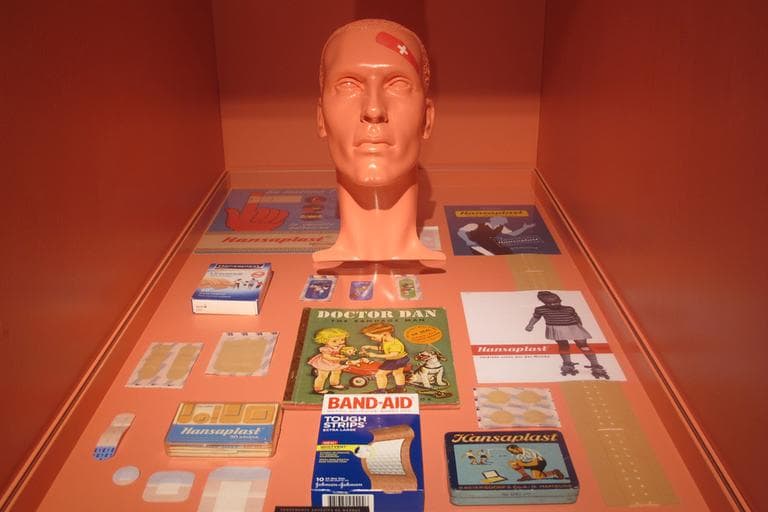

Then there’s the adhesive bandage, born in 1920. As the story goes, a cotton buyer named Earle Dickson who was working for Johnson & Johnson in New Jersey became incredibly frustrated by his wife's clumsiness — and constant bloodletting — in their kitchen.

"So he prefabricated a roll of gauze bandages for her, wrapped with adhesive," Van Zante said. The idea obviously worked. "And he brought the idea eventually to his employers, Johnson & Johnson, and they created the object that we know as the Band-Aid."

But it took awhile to get there, according to Van Zante. "It didn’t take off at first. They had to take it to the Boy Scouts of America as a publicity stunt to actually create a market for it."

Today, pretty much every American home has box of adhesive bandages, and billions of Band-Aid brand bandages have rolled off the assembly line since 1920.

The German Vitra Design Museum developed the traveling exhibition, at the MITMuseum through August. Olaf Kruger was on-site at the MIT gallery, and said he's installed the show in the Netherlands, Switzerland and England.

"In the end everybody loves it because it’s so colorful," he said during a short break from his work. "And there are so many things that everybody knows from his everyday life."

Van Zante hopes people will like it here, too. But he also mused about the past, saying some of these unassuming objects were likely the super stars of their day.

"In the 16th century, the first graphite holders — the precursors of the modern pencil — certainly were probably not thought to be very humble at the time, and probably would be a technological breakthrough very much like the cellphone would be today," he said.

Van Zante also wonders which of today's humble objects would get the love they deserve if MIT hosted an exhibition like this in 50 years.

This program aired on May 2, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.