Advertisement

Treat Hep C In Prisons? Could Cost $76B, But Break Epidemic

By Richard Knox

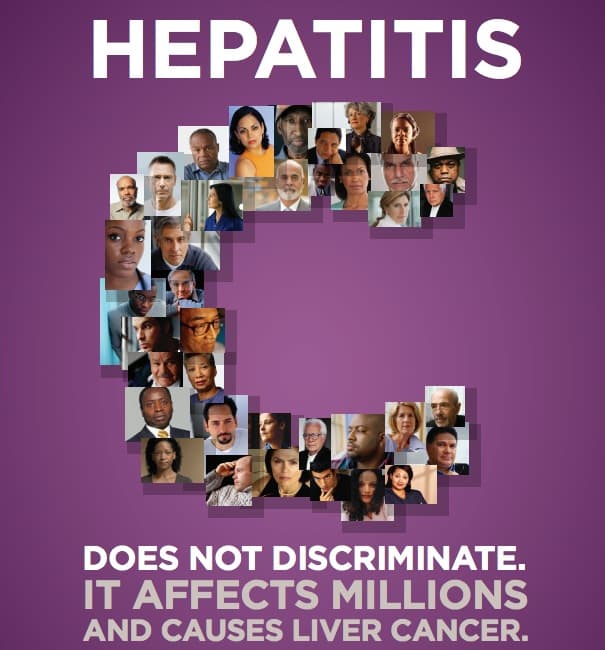

The hepatitis-C epidemic – five times bigger than the HIV epidemic – is finally getting the attention it needs, thanks to the sudden availability of costly new treatments that can cure almost everyone with this potentially deadly liver infection.

But there’s one big piece of the problem that almost no one talks about: the concentration of hep-C infections in the nation’s prisons and jails.

One out of six inmates has hepatitis-C, compared to something like one in 100 in the general population. Since the U.S. incarceration rate has soared in recent years, that means around 400,000 out of the 2.3 million American inmates are infected.

The reason is that most (but by no means all) hep-C infections result from contaminated needles and street drug use.

The hep-C epidemic is a catastrophic cost burden for the nation’s federal, state and local prisons. But it also represents a precious opportunity to get a jump on ending this insidious epidemic — the leading cause of liver failure, liver transplantation and liver cancer. So, who should pay, and how much?

First, the economic downside.

If all 17 percent of infected inmates were to get treatment – which could clear the nasty virus in almost all of them – it would cost at least $33 billion for the medication alone, according to the authors of an analysis in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine.

But that’s not the whole story. A lot more people cycle through US correctional facilities and jails every year; that number is something like 10 million. If only half of those got the new virus-clearing medications, the analysis says, it would cost about $76 billion.

What do those big numbers mean?

Well, total spending for medical care in 44 state prison systems was less than $10 billion. And that’s getting to be a strain on state budgets.

Dr. Scott Allen of the University of California Riverside, an author of the new analysis, points out that correctional facilities provide inmate care on a pay-as-you-go basis.

“Most prisons and jails are self-insured – they simply pay the medical bills,” Allen tells CommonHealth. “There’s no third-party insurance or spreading of the risks. So the economics get daunting.”

Now, not all hep-C infected inmates urgently need treatment, which costs $84,000 to $100,000 for the drugs alone. Some are in the early stages of infection, which can take decades to cause enough liver damage to put people at risk of liver failure or liver cancer.

But currently, no one knows what proportion of infected inmates need treatment. “There’s a brief window where these antiviral treatments are helpful,” Allen says. “But there comes a stage when it probably doesn’t help much at all. The earlier the stage (at treatment) the better the response.”

It’s not clear how federal and state correctional facilities will avoid paying for hep-C treatment for a substantial and growing proportion of inmates.

That’s because U.S. Supreme Court rulings have made it very clear that inmates are constitutionally entitled to receive the “community standard of care.”

“That’s not Cadillac care,” says Allen, who used to be the chief medical officer of Rhode Island’s prison system. “It’s what you’d expect to get minimally from a community health center if you were on Medicaid. But if you have a serious medical problem and there’s an effective or potentially life-saving treatment, the courts are going to expect adequate care” for prison inmates.

And if prisons don’t start providing the costly new treatments, Allen predicts that inmates will start to sue for access to it. “I predict they will prevail if the only argument against it is that [treatment] is too expensive,” he says.

Alarming as this situation is to correctional officials and government budgeters, it has a brighter side. The concentration of hep-C infections in prisons provides an important public health opportunity. Curing these infections would prevent infected people from spreading the disease to others.

“There’s a tsunami of death and disease that’s already starting to crash down on us, and will continue to in the decades ahead,” says Dr. Josiah Rich of Brown University, a coauthor of the new analysis. “But now that treatment can dramatically reduce transmission of this virus, we’re getting closer and closer to ending this epidemic. We argue that we should use the correctional system to do that.”

But how will that be possible, given the staggering cost, pinched correctional-system budgets, and a political calculus that doesn’t exactly favor allocating billions more on inmate health care?

“We’re not going to get a lot of traction on ‘let’s spend more tax dollars on the care of prisoners,’” Rich admits. “But I hope we can move the conversation beyond that to a public health perspective.”

Rich, Allen and coauthor Dr. Brie Williams of the University of California San Francisco argue that only the federal government can make the difference, along the lines of the 14-year-old Ryan White Care Act, which has allocated billions of dollars for HIV treatment.

Allen says only the federal government has the clout to negotiate lower prices for hep-C drugs for correctional facilities and other government programs. The model is so-called preferential pricing of HIV and hep-C drugs for developing nations.

“I would urge the drug companies to recognize some sense of corporate citizenship here and negotiate a lower price with government payers,” Allen says. “But we can’t be naïve about it. We live in a free-market system.”

Readers: Would you want your tax dollars to help fight the Hep-C epidemic among prisoners?