Advertisement

Studies: It May Be Better For Kids Who Are Overweight Not To Know It

According to the scale, the 18-year-old girl is severely obese. But she doesn't think so.

"I know I'm big, but I'm not obese," she says. "I don't take up three seats. My weight is high, but no higher than lots of people's. It's no problem."

If you're her doctor or school nurse or parent, what do you do? Do you bombard her with Body Mass Index charts and warnings of the health risks she faces? Knowledge is power, right? Certainly, that's the principle behind the "BMI report cards" — colloquially known as "fat letters" — that schools send home in some states.

But research just presented at ObesityWeek, a major conference on obesity, suggests that it may not be wise to persuade that young woman that she has a problem.

One study found that overweight teens who "misperceive" their weight as normal end up gaining less weight over the next decade or so than teens who are overweight and know it. Another study found that those "misperceivers" blind to their extra pounds were also less likely to become depressed in later years.

The findings are at odds with the basic assumption behind BMI report cards, that it is helpful to inform kids and their families of their weight status, says researcher Kendrin Sonneville, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health who is also affiliated with Harvard and the Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children's Hospital.

"I think we can say the jury is still out," she says. "Weight misperception is not something we should assume is harmful, and in the spirit of doing no harm, I think we need to proceed with caution on any type of programming that involves correcting weight misperception."

The study she led, which followed more than 2700 young people beginning in high school, found that after about a decade, the overweight teens who had perceived their weight accurately gained more than one BMI unit — very roughly about 10 pounds — more than those overweight teens who had falsely believed their weight to be normal.

Why might this be? That's one of the next avenues of research that need to be explored, but clinical psychologist Idia Thurston, an assistant professor at the University of Memphis, says the key could be the emotional baggage that comes with being told you're overweight or obese.

More accurate weight perception may translate into more feelings of stigma and lower satisfaction with your own body, she says, "and that could affect your ability to cope — hence, depressive symptoms or hence, engaging in harmful eating behaviors."

"So when we think about weight report cards and telling kids, 'This is what your weight status is,' you really need to think about how that information is being disseminated, and what kinds of protections are put into place, rather than just sending report cards home to kids and not knowing how kids will act on that information."

Dr. Thurston's study, also presented at ObesityWeek, found that overweight high-school-aged boys who accurately perceived their own weight as high were significantly more likely to develop depressive symptoms over the next decade or so. (The findings in girls were not statistically significant.) Once again, a false sense of being a normal weight appeared to be protective for overweight young people.

The idea of having schools screen kids for obesity began in 2003 in Arkansas during then-Gov. Mike Huckabee's anti-obesity efforts, Dr. Sonneville says, and spread around the country without ever having a solid research base on what its effects might actually be.

About one-fourth of states track schoolchildren's height and weight, and last year U.S. News reported that nine sent weight "report cards" home, including Massachusetts. But last October, facing pushback from nurses, parents and others, the state's Public Health Council voted to stop sending the letters home, though the schools still gather the information. U.S. News reported that decision under the headline "Massachusetts Schools To Stop Sending 'Fat Letters:'"

The council voted 10-1 to stop automatically sending the letters home, after parents expressed concern that the letters could promote bullying and perpetuate self-esteem issues.

Lynn Grefe, president and CEO of the National Eating Disorders Association, says sending BMI report cards home with students can make children more self conscious and potentially push them towards developing an eating disorder.

"It doesn't necessarily lead them to healthier behaviors, but rather among some, it leads to unhealthy behaviors - laxative abuse, purging, excessive over-exercising, dieting - all things that are risky in developing eating disorders," Grefe told U.S. News. "If we would all focus on the word 'health,' rather than weight and size, we would see better outcomes."

Past research had found that kids whose weight was normal but who misperceived themselves as overweight were at heightened risk for eating disorders.

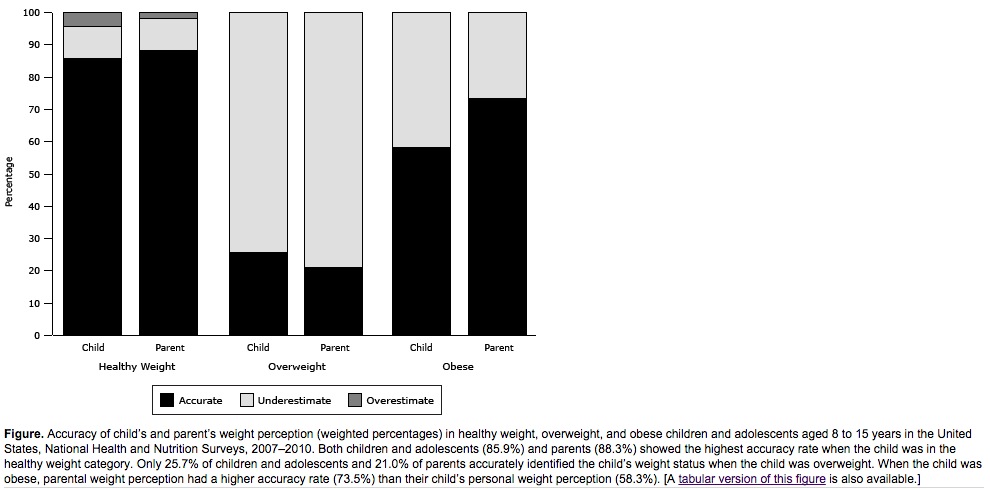

Now, the work by Sonneville and Thurston opens up a new avenue of research, on kids who "under-perceive" rather than "over-perceive" their weight. They are surprisingly common: a CDC report this summer found that about three-quarters of overweight American kids think their weight is normal. (The two middle bars in the chart below show that both children and parents tend to under-perceive the weight of overweight kids.)

It was frequent encounters with patients like the 18-year-old woman described above, in the PREP weight management program at Boston Children's Hospital, that made Sonneville, Thurston, and Dr. Tracy Richmond, the senior author on both studies, want to examine the premise that it is necessarily bad for a young person to underestimate their own weight.

“There’s a clinical assumption that someone has to really hate their body to make healthy changes,” Dr. Sonneville said. “I always wondered how self-hatred or anything so negative could be motivating.”

The next step in the research, she says, should be to look at schools where BMI report cards are sent out and schools where they are not, to compare effects on weight, mood and other measures over time.

Dr. Thurston says more research is also needed to see whether self-image — what's called "body satisfaction" — is the key to the negative effects of correcting weight perception.

And already, Dr. Thurston says, the findings suggest that kids and their parents should not get those BMI "report cards" without more help on what to do about them.

"That touches on tricky issues of bringing exercise back to schools, and bringing healthy diets back to schools, and who bears the costs of those things?" she says. "But we can't just disseminate information without thinking about how to help families cope with it. Because when we do, we're creating this uncomfortable situation which could actually be harmful."

Readers, agree? Disagree? Thoughts?