Advertisement

This 'Romeo' Educates Men About Domestic Violence

For Antonio Arrendel, educating men about domestic violence is “a lifestyle.” He says that like his artist friends, “I do what I do whether or not I get paid.” As it happens, that was exactly the attitude needed to participate in a new documentary film about his life and work as a “batterer intervention specialist.”

Arrendel is the subject of Boston filmmaker Lorna Lowe’s much-anticipated second feature-length documentary, "Romeo," premiering on Thursday at 6 p.m. as part of the Roxbury International Film Festival. The festival, which takes place June 17-28 at the Museum of Fine Arts, was created to showcase films by and about people of color.

Here's the trailer:

Lowe served up a searing self-portrait of adulthood as an adopted child in her first documentary, “Shelter,” in 2002. It garnered awards, critical praise, and paved the way for her to start a second film with funding from Women in Film & Video New England, LEF Foundation, Color of Film Collaborative (the overseeing body of the Roxbury International Film Festival) and a residency at WGBH.

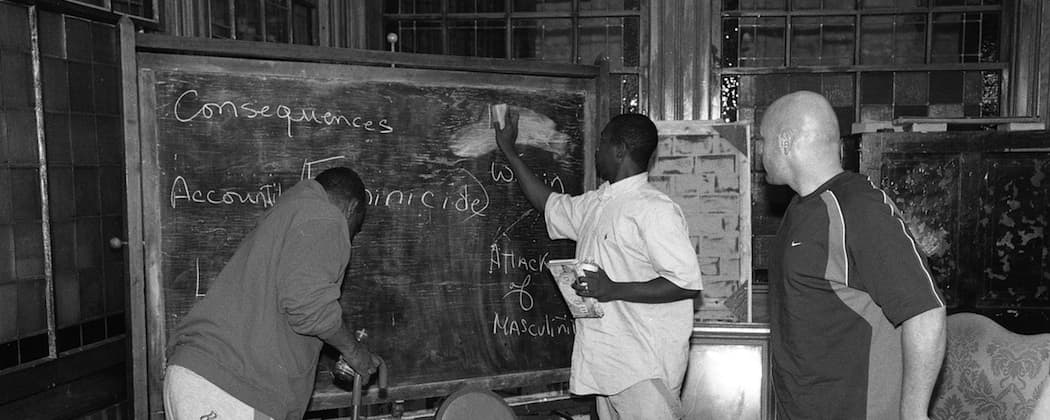

Lowe’s support also came from the fact that she’d zeroed in on an under-reported topic: the men behind men’s violence against women. For more than a year she observed “rehabilitation” groups for men led by Common Purpose, a Boston-based nonprofit—one of the first in the nation to educate men about their role in the cycle of interpersonal heterosexual violence. Antonio Arrendel was one of the facilitators.

“We immediately clicked,” says Lowe about her collaboration with Arrendel. Though she started with the plan to investigate the topic at large, over more than 10 years and “I can’t even tell you how many [story] iterations,” the film evolved to be a character portrait of Arrendel, an articulate and gregarious man who transformed himself from “Tony,” who dealt drugs and owned guns, to “Antonio,” husband, father of four and community leader.

“Romeo” is, at times, poetic (the opening montage of Arrendel riding his bike from Cambridge to Boston is a love letter to 1960s European cinema), raw (male perpetrators talk openly about mistreating their female partners) and wise (a tough kitchen-table conversation between Arrendel and his wife is a generous example of a non-violent quarrel). It is also sometimes puzzling as the storyline favors subtlety over explication.

So “Romeo” is not a film about statistics or policies. More compellingly, through Arrendel, it names the social constructs that allow men’s abuse of women to persist. When one man in Arrendel’s group (about five participants agreed to filming) says his girlfriend is the one who got him there, Arrrendel interrupts. “Who got you here?”

“Vanessa,” says the participant.

“You mean she dropped you off?” Arrendel jokes but his point is undeniable.

Whether he’s interacting with men court-ordered to complete Common Purpose’s 40-week program or speaking to the camera in the one interview that runs throughout the film, Arrendel sums up what he sees in language that is clear, fresh and memorable. When Arrendel’s wife throws a mango at him then says it was a “reflex,” he reminds her, “We talk about violence being a choice.”

Lowe says that as years went by it was challenging to field well-meaning questions about her film’s status. And the age of Kickstarter, when a filmmaker is supposed to build an audience alongside (if not before) building a film, only magnifies the scrutiny. Not only did Lowe have to deal with formats from six different cameras including standard definition, she says that mid-production she realized, “I can’t use another person’s hands and brain [to edit the film] because something gets lost.” Learning to edit, she says, “was so freeing.”

A few years in, she also made the decision to include Arrendel and his family in the filming process. “[Antonio] would call me and say, ‘Guess what happened last night?’ ” She gave him a camera to capture those moments and he did so, prolifically. It took time to sift through the footage. She found tapes full of revealing, confessional scenes.

At first she thought, “I don’t know who this is.” She’d been crafting a hero’s story around a man who was more complex than she realized. Then it dawned on her: “He has given me the tools to make a much more powerful film.”

According to Roxbury International Film Festival director Lisa Simmons, other films playing with local ties include: "Circus Without Borders" on June 18 at 8:30 p.m.; "An Unexpected History: Hennessy and African Americans" on June 19 at 6 p.m; Shorts Program 1: Youth, Identity, and Consequences (which includes short films by Roxbury’s Madison Park High School students and "Evolution of a Bully") on June 20 at 11 a.m; and "Black Lives Matter and Passage at St. Augustine" (screening together) on June 25 at 8:30 p.m.

Erin Trahan is a regular contributor to the ARTery. She also edits The Independent and just finished her sixth Frommer’s Easy Guide to Montreal and Quebec City.