Advertisement

'Invisible Nation': A Look Into America's — And Boston's — Homeless Families

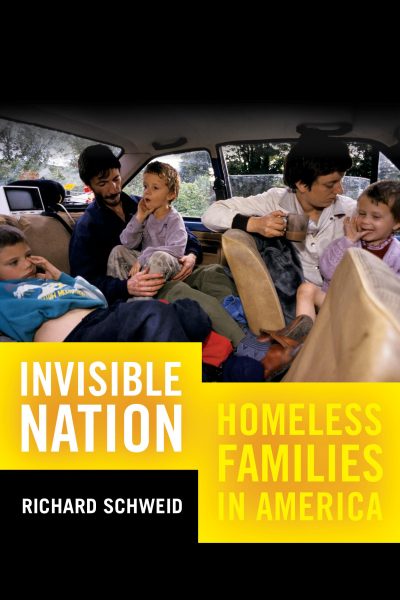

Unlike homeless individuals, whom you may pass on a city sidewalk, homeless families exist mostly unseen. They might temporarily stay with relatives, in an available shelter, a cheap motel or their car. This hidden-in-plain-sight aspect compelled Richard Schweid, a documentary reporter and the author of nine previous nonfiction books, to embark on a years’ long, multi-city study of homeless families. The result is “Invisible Nation: Homeless Families in America.”

To underscore how widespread this life-shattering situation has become, Schweid provides a sobering statistic: “In 1980 families with children made up only 1 percent of the nation’s homeless; by 2014 that number was 37 percent of the total.”

Since the turn of this century, causes of the dramatic rise in homeless families are numerous: low-wage jobs with no benefits, high rents, crushing medical bills, domestic violence and harsh changes in rental and eviction laws. To all this, add the long, bruising impact of the Great Recession.

Beginning in 2003 and continuing past the Recession, Schweid lived for a few months at a time in Nashville (his hometown), Boston, Fairfax (Virginia), Portland (Oregon), and Trenton (New Jersey), interviewing homeless families and agencies that serve them. The U.S. does not have a nationwide policy for the homeless; each state creates its own agencies and solutions. Schweid’s travels convinced him that the “luck of the 2.5 million children estimated to be homeless at some time each year in the United States will depend in part on the state in which they find themselves.”

For example, since 1983 Massachusetts has been one of only two states (besides New York) that has a right-to-shelter law for families with children. If a family at risk of homelessness meets certain eligibility requirements, they are immediately placed in a shelter or motel.

But shelters and motels are at best short-term solutions. A motel is a uniquely unhealthy environment for families. There are no safe areas for children to play, no laundry facilities or grocery stores nearby, and the room’s only cooking appliance is a microwave. Schweid details the different homeless strategies put forth by former Massachusetts Govs. Romney and Patrick, one replacing the motel program with a shelter-to-housing voucher program, and the other with HomeBASE, a rental subsidy program. In recent years, Massachusetts, like other states, has had to tighten eligibility requirements as budgets have shrunk, so more homeless families nationwide have been left out of the system.

Schweid creates some vivid portraits of day-to-day struggles, but too often he overwhelms the narrative with waves of statistics. The sheer volume of data included on housing, jobs, shelters, agencies and families — at times without a cohesive storytelling arc — dilutes the power some of these statistics might have. Using a wide lens on this considerable topic is admirable, but tightening the view, with a more targeted set of data, may have made some of the accounts of agencies and policies more memorable.

Schweid’s writing is most resonant when he describes the toxic effects of chronic homelessness on young children. It’s difficult to collect meaningful data on a population that frequently moves, but what is collected exposes appalling conditions. Homeless children have the same ills as those of impoverished children who are housed, but magnified. They have more chronic ills like asthma, ear infections, malnutrition, stammering, eczema. With few places to crawl and explore as babies, or to play as kids, or few chances to get truly settled in at school, they often have delayed development and behavioral problems. With extreme volatility in their daily lives, they are more frequently the witnesses to, or victims of, violence or sexual abuse.

The question is, and has always been, who among the poor deserves our help and how much of it should we provide?

Richard Schweid

Amid these devastating scenarios, Schweid also highlights many individual acts of compassion, like the Nashville elementary school teacher who keeps a classroom cupboard stocked with new clothes in different sizes for students whose families are recently evicted and have watched their belongings hauled away.

To show how we got here, Schweid offers an illuminating history of U.S. policies on the poor, from 17th century New England. For this, he poses a query that is at the heart of “Invisible Nation” — “The question is, and has always been, who among the poor deserves our help and how much of it should we provide?”

In Colonial America, there were citizens viewed as hard workers who’d fallen on tough times, and there were the “idle poor” (a term President Reagan would rename as “welfare queen”). But for the most part, poverty was seen as “an economic problem with an economic solution.” To help their own families, impoverished children were temporarily sent out to other families to work in exchange for housing.

As towns became more populated, officials began to gather “all the desperately poor together in one place,” in the almshouse (aka the workhouse or poorhouse). Boston’s first almshouse opened in 1662, and many more would be built across Massachusetts into the 1800s. Criminals, families and the mentally ill were all housed under one roof.

An almshouse essentially made the poor invisible to the rest of the town, and thereby altered the way other citizens viewed poverty: it was caused, not by tough circumstances, but by a failure of character. This tension between a no-fault and idle-poor view would weave its way throughout our history, as with President Johnson’s 1960s War on Poverty with assistance agencies like Head Start and Job Corps, and President Clinton’s 1990s welfare reform titled Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

Ultimately, Schweid makes a forceful case for solely economic solutions for homeless families: moving them into affordable rental housing and letting everything else flow from that (including, critically, a chance at steady employment). This approach may also benefit the local community, which may save money in the form of less crime and fewer strains on schools and emergency services.

You close the book wondering where those millions of homeless children will sleep tonight.