Advertisement

‘Make Way For Ducklings’ Creator Robert McCloskey Showcased In MFA Exhibit

Robert McCloskey landed in Boston during the Great Depression, having won a scholarship in 1932 to study at Vesper George School of Art.

The Ohio native had aspirations to make it big as a fine artist. He assisted Francis Scott Bradford in painting murals of the Massachusetts State House, the Charles River, Louisburg Square and other Boston scenes at the Lever Brothers Building (now part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) in Cambridge. He drew syndicated cartoons. He painted watercolors in Provincetown.

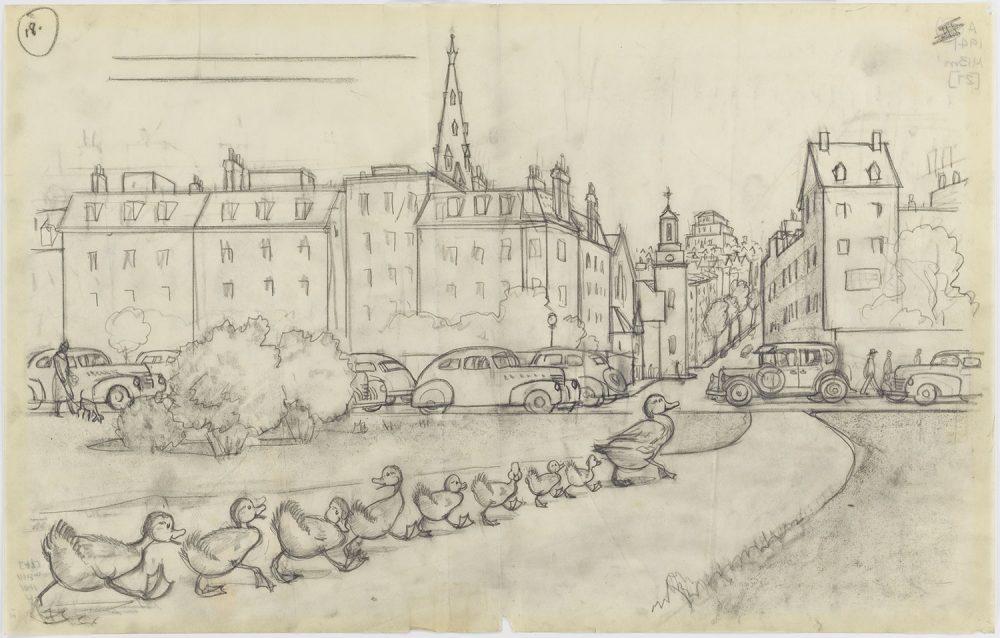

And on his way to art classes on St. Botolph Street, McCloskey (1914 - 2003) sometimes passed through the Public Garden and fed the ducks. It was those ducks who would inspire McCloskey’s most famous artwork, his now classic 1941 picture book “Make Way for Ducklings.”

The tome turned 75 this year, and is the centerpiece of the exhibition “Make Way for Ducklings: The Art of Robert McCloskey” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts through June 18, 2017, which showcases drawings and paintings spanning McCloskey’s entire career.

“It was a story that was just in his memory bank,” says H. Nichols B. “Nick” Clark, who organized the exhibition. (Clark was the founding director of The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, where the show debuted last summer. He retired from that museum in 2015.)

"I had first noticed the ducks when walking through the Boston Public Garden every morning on my way to art school," McCloskey once told The New York Times. "When I returned to Boston four years later, I noticed the traffic problem of the ducks and heard a few stories about them. The book just sort of developed from there."

'Go Home And Write About What You Know'

After studying art in Boston and at New York’s National Academy of Design, McCloskey struggled to sell his watercolors. Looking for work, he approached May Massee, the children’s book editor at Viking Press, and the aunt of a high school friend.

"She looked at the examples of 'great art' that I had brought along (there were woodcuts, fraught with black drama)," he later told The New York Times. "I don't remember just the words she used to tell me to get wise to myself and to shelve the dragons, Pegasus and limpid pool business."

The gist of it, McCloskey’s daughter Jane McCloskey wrote in her 2011 book “Robert McCloskey: A Private Life in Words and Pictures,” was, “Lighten up. And go home and write about what you know.”

So he returned to Hamilton, Ohio, where he grew up, then came back to New York and drew. In 1939, he showed what he’d come up with to Massee and she arranged for them to be published as “Lentil” (1940), the first children’s book he authored and illustrated.

It's the story of a boy by the name of Lentil learning to play the harmonica and a town crank who refuses to be impressed by “the town’s most important citizen,” the richest man around, who built the town library and war memorial too. “He ain’t a mile better’n you or me and he needs takin’ down a peg or two,” the crank proclaims. The whole populace gathers at the train station when the plutocrat pays a visit back home. The crank tries to spoil the welcome by disrupting the brass band, but the boy saves the day by tooting his harmonica.

Security Of Family

McCloskey’s next solo project, ''Make Way for Ducklings,” won him his first Caldecott Medal, the most prestigious prize for American picture books for children.

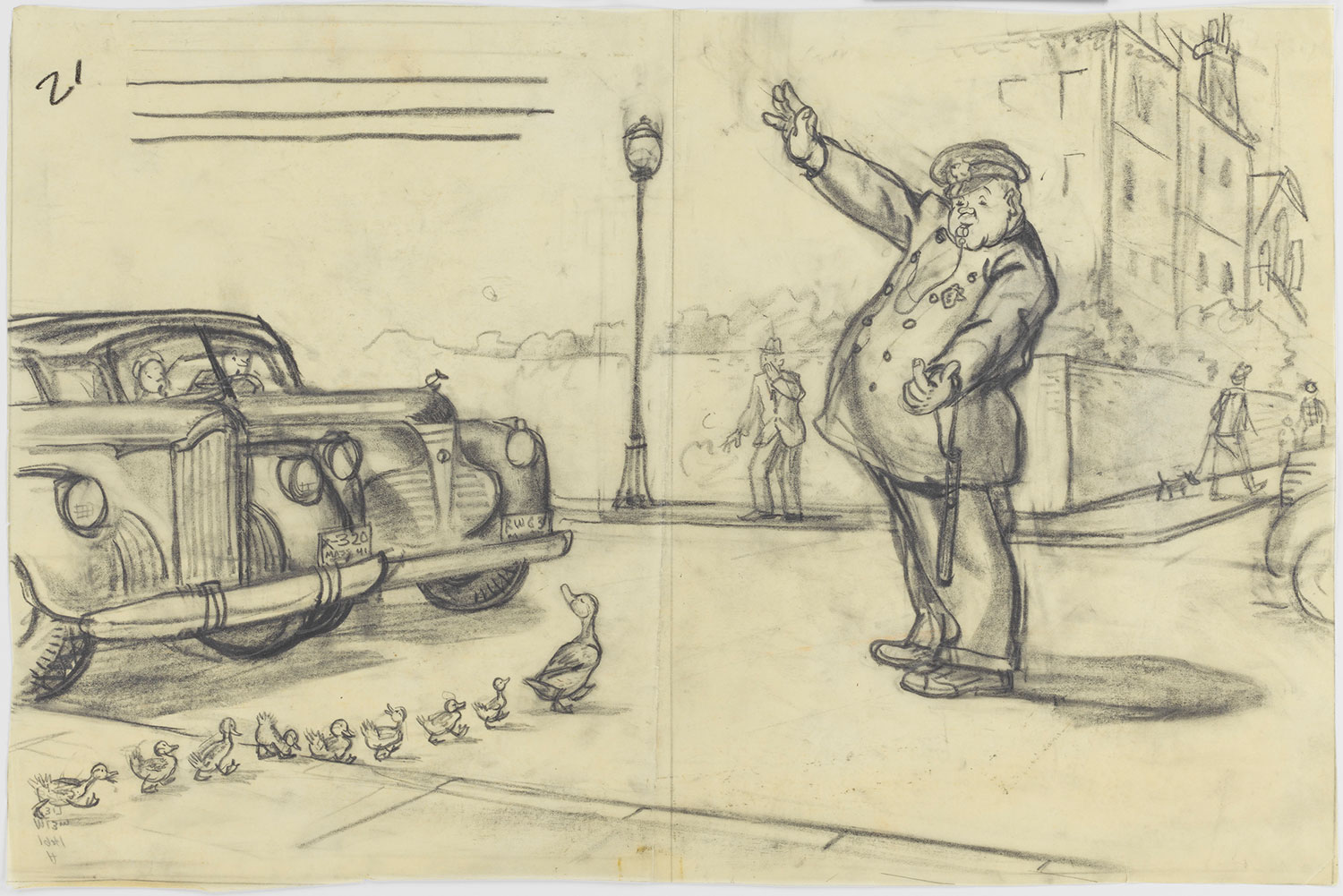

In the book, two mallards look for a place to nest and raise their babies. They pick a Charles River island, but Mr. Mallard goes off wandering, leaving the Mrs. Mallard to raise their eight ducklings (Jack, Kack, Lack, Mack, Nack, Ouack, Pack and Quack) on her own until they rendezvous at the Boston Public Garden. Getting there proves troublesome — their route crisscrossed by roads abuzz with speeding cars. Luckily, Michael the police officer and his comrades provide assistance. The ducks make a new home on an island in the park’s lagoon, where Mr. Mallard meets them.

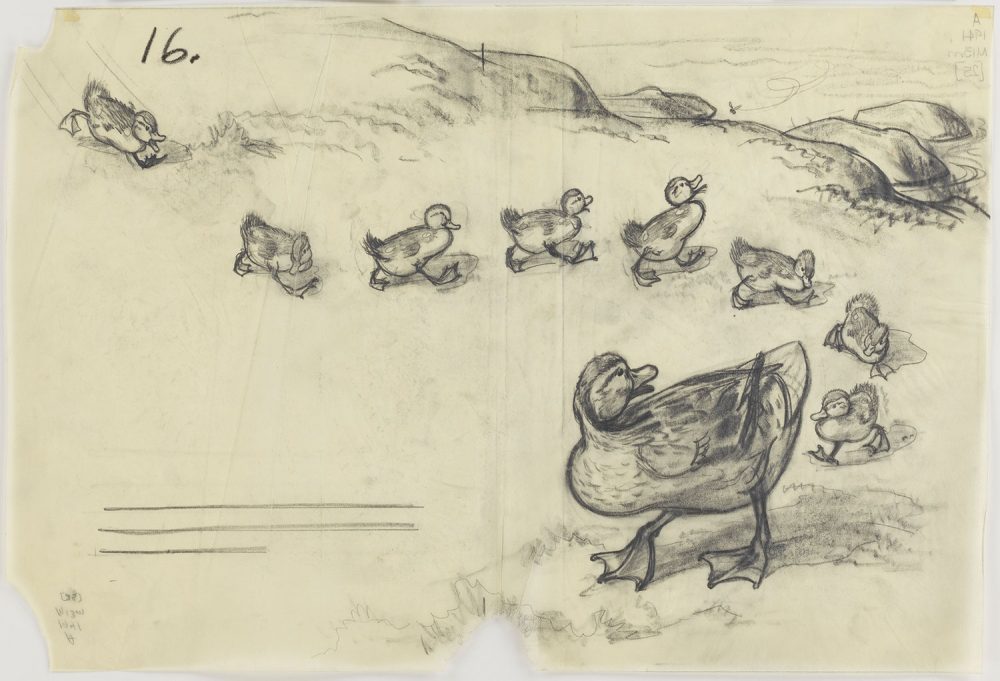

In person, McCloskey's drawings are remarkable for their virtuosity. “His skill as an artist does shine in ‘Make Way for Ducklings’ in particular. He had a very accurate eye for detail, a skilled draftsman, but he was also able to show the world from different vantage points,” says Meghan Melvin, a design curator at the Museum of Fine Arts. “You are sort of seeing it from the duck’s vantage point. I think that’s what’s distinctive about McCloskey’s work — his ability to show the world either from children’s point of view or, in this case, a duck. I think he had a deep, rich imagination.”

Dedicated to realistic accuracy, McCloskey drew stuffed mallards at the natural history museum. Then he filled the apartment he shared with loudly quacking live ducks.

“I’d moved from Boston to a studio apartment in New York City, and though I returned to Boston to make sketches, it was cold weather and rainy and very unpleasant and I soon realized I couldn’t study ducks there,” McCloskey recalled to Leonard Marcus (as recorded in his 1991 book “Show Me a Story”). “Then an anthropologist mentioned that I could buy live ducks at a certain Greenwich Village market. So I did, brought them home, and kept them in the tub.”

“He said, ‘I spent a lot of time running after them with Kleenex tissues,’ ” Clark says. “As the story goes, if they got them a little bit of wine that calmed them down.”

"Whether it’s World War II or the Cold War, Bob provided books that had this sense of reassurance to them. Everything always works out for the best in the end."

H. Nichols Clark

“What really comes through in his books is this really remarkable value system that he had,” Clark adds. “It’s right out of an Andy Hardy movie. It’s right out of that period. He’s sort of the picture book equivalent of Norman Rockwell.”

It set the style for all his picture books to come. They are reassuring tales of parents and children and helpful authority figures in an amber-hued mid-20th century, small town, white America.

“It never occurred to me that it would be taken as exemplary of family life,” McCloskey told Marcus. "But there must be some reassurance in a story about a father mallard making a promise to return and then keeping that promise.”

“It’s about the security of a family,” Clark says. “Whether it’s World War II or the Cold War, Bob provided books that had this sense of reassurance to them. Everything always works out for the best in the end.”

Maine Inspirations

McCloskey had never visited Maine before he summered with his wife Margaret “Peggy” Durand, a librarian whom he married in 1940, and her parents in Hancock in 1946. But it is with Maine that he would become most identified.

That summer inspired the couple to buy an island home at Penobscot Bay, near Little Deer Isle. With their daughters Sal, born in 1945, and Jane, born in 1948, they would spent five months of each summer there, then around October would head to Massee’s home at Croton Falls, New York, for the winters.

In between a stint in the military in World War II (mainly at Fort McClellan, Alabama) and illustrating books by other authors (Anne Malcolmson’s 1941 book “Yankee Doodle’s Cousins”; Claire Huchet Bishop’s 1942 book “The Man Who Lost His Head”; his mother-in-law Ruth Sawyer’s 1953 book “Journey Cake Ho!” for which he would win a Caldecott Honor, a runner up to the top prize), he worked on his Mark Twain-esque, Ohio-inspired “Homer Price” tall tales, which were published in 1943.

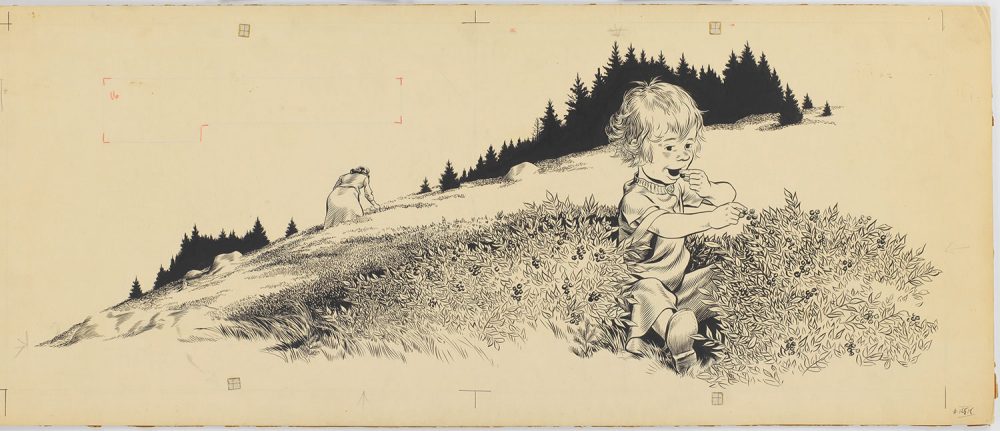

McCloskey’s young family would inspire his next picture books. “Blueberries for Sal,” his Caldecott Honor-winning book of 1948, is about his wife and daughter and a bear and her cub gathering blueberries on the same mountain — and the comedy that ensues when the young ones mistakenly end up following behind the wrong mothers.

"He had the ability to look at his surroundings and find episodes that he could mine."

H. Nichols Clark

“One day I had taken my wife and daughter and had taken along my sketchbook and was just lazing there, almost dozing away in the sun when I heard this kuplink, kuplank, kuplunk of the berries striking the bottom of Sal’s pail. I guess that was what set the whole thing off,” McCloskey told Marcus. “The bears were imagined, though meeting up with bears in Maine while blueberring used to be a pretty common occurrence.”

“He had the ability to look at his surroundings and find episodes that he could mine,” Clark says.

That said, though “Blueberries for Sal” is set in and inspired by Maine, McCloskey sketched blueberry bushes at the New York Botanical Garden and drew the bears based on critters he saw at New York’s Central Park Zoo.

McCloskey’s Caldecott Honor-winning 1952 book “One Morning in Maine” was inspired by clamming with his daughters. It’s a tale about a lazy morning with the girls on their Maine island, wiggling a loose tooth, digging clams, then taking the boat into town to get groceries and have the outboard motor repaired.

His 1957 book “Time of Wonder” is a reverie about nature as his daughters play on the shore and waters around their island. People get ready for winter. Then a hurricane blows in. The storm was inspired by Hurricane Edna of 1954 — when, his daughter Jane McCloskey recalled, he pressed towels against the bottom of their home’s French doors to keep the wind out, when waves crashed to within 15 feet of their door, when a tree fell upon their roof. The book would win him a rare second Caldecott Medal.

“A lot of the life you see in these stories was his life,” Melvin says. “His life on an island in Maine is documented quite closely. I wonder if the authenticity and the sincerity resonates.”