Advertisement

To Detect Threats And Prevent Suicides, Schools Pay Company To Scan Social Media Posts

ResumeWalk through the front door at Shawsheen Valley Technical High School in Billerica and the first thing you notice is security.

"Everyone who visits the building, when they come into this secure foyer, has to scan a driver's license or another state-issued ID," explains Superintendent Tim Broadrick. "It does kind of a high-level national background check."

The "LobbyGuard" scanner is the size of a computer tablet. It scans a driver's license, takes a picture of the school visitor and if all is OK with the person's background check, almost instantly clears the person to enter the school.

An employee behind a window then pushes a button and unlocks the door to the school hallway.

An 'Alarm System' Through Social Media

Amid nationwide concern about school shootings, there's talk at Shawsheen Tech of covering the wall of glass in the lobby with a special film to make it harder for a bullet to pierce.

There's also a police officer — known as a school resource officer — stationed at the school. He has an office in the lobby.

And the school has adopted another security measure to try to protect students from attacks — one you can't see. It's a computer program designed to detect threats against the school in social media posts. And it runs 24/7.

"It's receiving and filtering and then gives us alerts when certain kinds of public communication are detected," Broadrick explains.

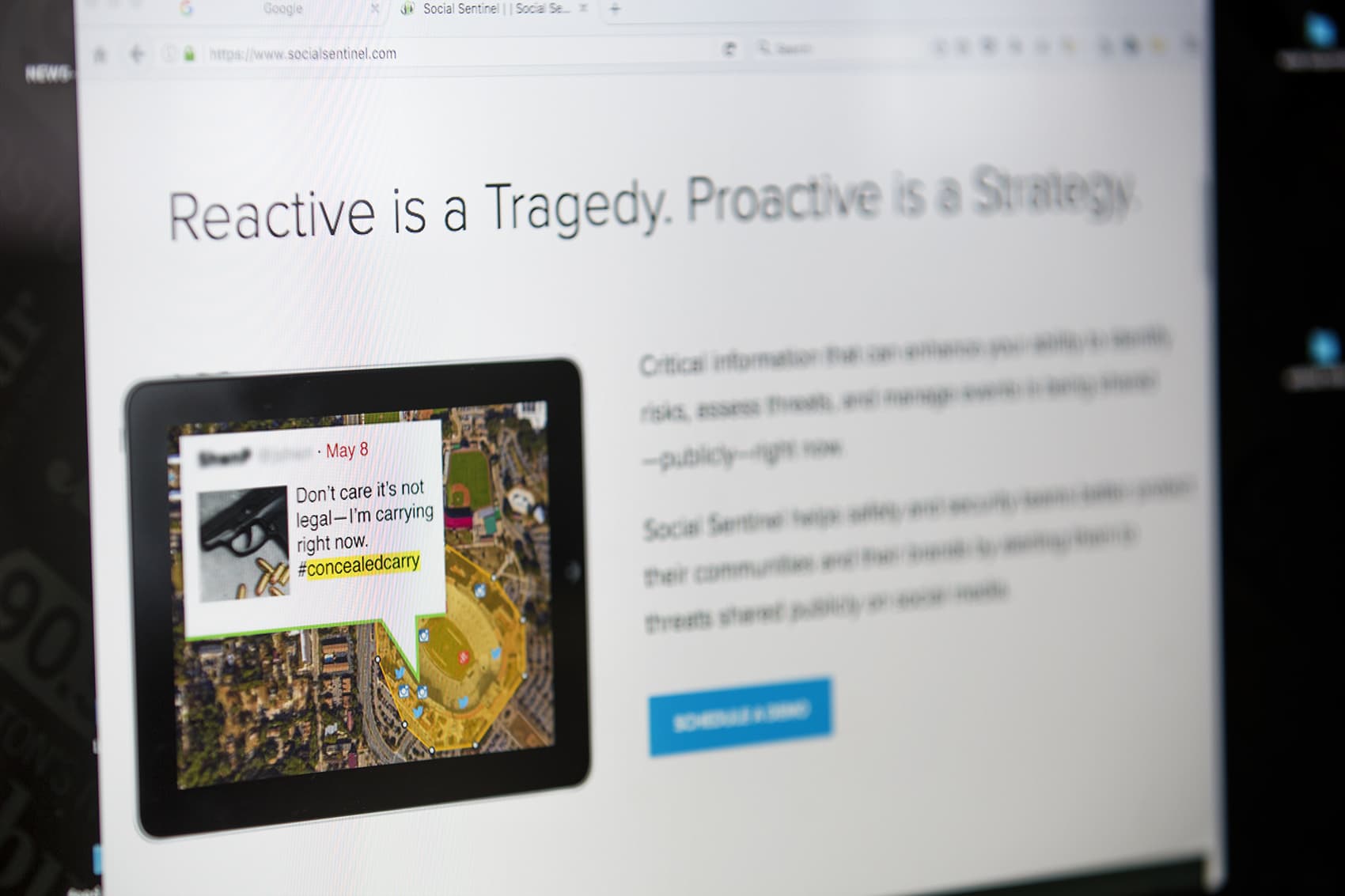

Shawsheen Tech buys the social media scanning service from a Vermont-based company called Social Sentinel. It's one of many technology firms doing some form of social media scanning or monitoring. Social Sentinel claims it's the only one with expertise in protecting schools.

Shawsheen Tech has about 1,300 students. It pays Social Sentinel approximately $10,000 per year, according to Broadrick.

Gary Margolis, Social Sentinel's founder and CEO, describes the service as a "home alarm system ... for social media."

"We are not a surveillance tool; we are not a monitoring tool; we're not an investigative tool," he adds.

Margolis says the software scans about a billion posts every day, from a dozen social media platforms including Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. It's looking for so-called "language of harm" associated with the schools paying for the software.

Social Sentinel worked with experts in linguistics, mental health and public safety to build a "library" of more than 450,000 words and phrases that set off its algorithm's alarm bells, according to Margolis, who is a former Burlington, Vermont police officer and University of Vermont police chief.

"We went back, for example, and looked at the language that school shooters, as one example, have used in the past in various manifestos — what's been published or that they've shared on social media," Margolis explains. "And we went to understand similarities and patterns. And we can teach computers, to an extent, how to identify some of that nuance."

But not all of it, he acknowledges. So there are "false positives," or false alarms, with the software — alerts for posts that don't contain a threat.

Scanning For Threats Of Suicide

The software isn't meant to only pick up on threats of violence. It's also looking for social media posts from students indicating they might hurt — or even kill — themselves.

Broadrick, the school system's superintendent, says Social Sentinel's services proved their worth early on because of that.

"One of the alerts that they sent us indicated that one of our students' mental health condition was deteriorating, maybe to the point that that student's life could have been in danger," Broadrick recalls.

The program had picked up on key words the student used on social media and alerted the school. School counselors found out the student had an imminent suicide plan. They got the teenager help.

The town of Arlington had a similar experience using Social Sentinel. Arlington Police Chief Fred Ryan says the program alerted police to a student whose social media post indicated suicidal thoughts, and they were able to intervene.

"It's about being proactive rather than reacting to terrible events," Ryan says of using the social media scanning technology.

'Aware Without Compromising People's Expectation Of Privacy'

Ryan says the department gets anywhere from two to about 10 alerts per day. A few members of the department receive them -- either by email or text — and one detective is in charge of going through them to look for threats. On most days, the alerts are benign.

Arlington police use Social Sentinel to be alerted to threats only against Arlington schools and students. Social Sentinel once sold its services directly to police; now it only sells to school districts, colleges and event arenas.

Ryan shows us an alert email he received on the day we're meeting with him. It links to a Twitter post from an Arlington resident. The post contains the term 'gun violence.'

"This person is obviously advocating for anti-gun policy. So right there, it's not a credible threat," Ryan says. "We move on."

Chief Ryan says looking at the alerts that don't indicate a problem isn't a waste of his time or his officers', and he isn't bothered by looking at people's social media posts, because they're posts that are set to public. Social Sentinel doesn't scan the private ones.

"We feel strongly that this service enables us to be aware without compromising people's expectation of privacy, civil rights and sort of government lurking around social media accounts. That's not what we do," Ryan says. He adds that Arlington's Human Rights Commission endorsed the use of Social Sentinel.

Concerns Surveillance Violates Civil Liberties

But the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts has concerns about the program's use.

"This is an expansion of the schools' ability to police what students are doing inside of school or on campus to their outside-of-school conduct," says Kade Crockford, who directs the Technology for Liberty Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts.

Crockford says though this kind of technology may not violate people's constitutional rights, it does raise concerns about civil liberties: The program casts a wide net and the public doesn't know what words and phrases it's searching for among the half-million or so search terms.

For example, a student might post something about smoking pot on the weekend. If the post contains one of Social Sentinel's hot-button words — even if there's no threat of violence or suicidal behavior — school officials will receive an alert.

"In many cases across the country, schools have been using social media surveillance tools in ways that have harmed, specifically, students of color. So we certainly have concerns about technologies like this being used to expand what we call the school-to-prison pipeline," Crockford says.

"In many cases across the country, schools have been using social media surveillance tools in ways that have harmed, specifically, students of color."

Kade Crockford, with the ACLU

Crockford's concerns are reminiscent of a controversy in Boston two years ago. It came to light that a Boston police intelligence unit had been monitoring social media accounts of Bostonians.

In a 2017 report, the ACLU said it found the city's officers were using an outside company — not Social Sentinel — to seek out posts that contained terms including 'protest,' 'Black Lives Matter' or 'Muslim Lives Matter' — and that the practice did not prevent any serious crime. Crockford calls it "digital racial profiling."

The Boston Police Department disputed that claim. They said the technology helped them monitor how people in Boston were reacting to police shootings and other events involving race around the country so they could detect whether demonstrations might spring up here. They said they did not use the technology to target individuals for surveillance.

Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox says social media scanning brings up another set of problems for law enforcement and school administrators.

Fox makes the case that it's extremely difficult to predict who will carry out a crime like a mass shooting at a school, because those are still very rare events. He says many thousands of people on social media are fascinated with guns, violent video games and dark song lyrics — but would never turn violent.

"Trying to identify — out of the 55 million school children — the small handful who are really dangerous is not easy," Fox says. "The more and more we try to find people and lower that threshold of what is it that's going to trigger an investigation, we're going to identify lots of people who aren't dangerous, for whom it's — they want to be a big shot, but they're not going to take a shot. And what's going to happen to them? That suspicion itself could turn their lives in the wrong direction."

"Trying to identify -- out of the 55 million school children -- the small handful who are really dangerous is not easy."

Northeastern criminologist James Alan Fox

Fox says social media scanning might be useful to prevent suicide. Suicide is common, and he says the clues people give on social media can be overt.

One college that's recently grappled with higher-than-average rates of student suicide is MIT. The school confirms its police and emergency management personnel have been using Social Sentinel since 2015.

Students we spoke with weren't aware of its use on campus. MIT junior Milka Piszczek says as long as students' social media posts are already public, it might be helpful for authorities to check them out — especially if a student is suicidal and crying out for help.

"You're kind of yelling into this void, but the void is literally full of hundreds of thousands of posts," Piszczek says. "It's possible that no one who cares will see it, even though there are people who care. So if there is a technology that can help pick out those posts that might need that extra attention from a person, it's a pretty good solution."

MIT freshman Jonathan Tagoe says he's concerned about racial bias in any social media scanning or monitoring. But he thinks MIT can use the technology wisely.

"I think it could be helpful," Tagoe says. "It's just, like, not letting it become too intrusive. Also, just making sure that you're not targeting people who aren't meaning any harm."

Social Sentinel officials said its library of words and phrases that trigger alerts is proprietary information and cannot be shared with media.

The company can't yet demonstrate, with data, how effective its software is at identifying threats. But Margolis says he hears from clients all the time that the technology has helped keep someone from hurting themselves or someone else.

This segment aired on March 22, 2018.