Advertisement

'Under A Dismal Boston Skyline,' These People Are Making Great Art

What’s it like to be an artist in Boston?

Well, first you get ignored by the big museums who are only interested in showing you if you live in New York. You find your work is too weird, too different, to appeal to conservative art buyers looking for that elusive Picasso or Monet. The old warehouse where you used to rent studio space gets turned into luxury condos.

And if you think these are only the problems of today’s artist, think again. It’s been this way for decades.

Yet, somehow, artistic experimentation flourishes in Boston.

Now an exhibit at Boston University’s Stone Gallery, “Under a Dismal Boston Skyline” examines the art coming out of Boston, tracing a loose lineage of artists working in the city from the late 1970s and 1980s, all the way up through the present day. Collectively dubbed “the Boston School,” (not to be confused with the Boston School of painting of the early decades of the 20th century), the artists, most of whom were students or graduates of The School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, worked from the margins of the art world, as it seems that Boston artists often do. They were social outsiders, often with ties to gay and transgender culture, shooting selfies and moody photos of their friends and acquaintances, creating videos and putting on performances for themselves and their community. They were rebels who reveled in the dangerous excitement of punk culture and the underground, not interested in belonging to The Copley Society but still nurturing dreams of becoming famous. (And many of them did.)

At the center of this group was Mark Morrisroe, (whose photograph “Under a Dismal Boston Skyline” became the title of the show), Nan Goldin and David Armstrong, each included in this show. Many of these artists, including, Morrisroe himself, would later move on to New York, but all got their beginnings in politically-progressive but culturally-conservative Boston, which provided just the right amount of “tame” for their wildness.

“These artists were working very much outside of any mainstream cultural institutions and any formal community of artists,” says Lynne Cooney, artistic director at the Boston University Art Galleries who curated the exhibit along with Evan Smith, media coordinator for BU’s School of Visual Arts, and Leah Triplett Harrington, an arts writer and independent curator. “They were part of a marginalized culture, not just artistically but also just in terms of punk rock for example or the nightlife scene. They were all kind of interconnected in that way.”

The show features 24 artists of whom Goldin, Morrisroe and Armstrong may be the best known. Goldin, who currently lives between New York and London, is known for her candid portraits of drag queens and transgender friends shot with almost a voyeuristic immediacy.

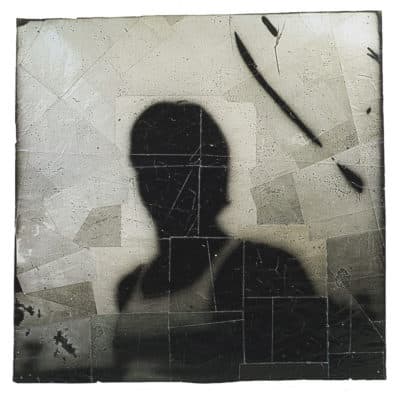

Morrisroe, who died in 1989 at age 30 from complications of AIDS, also became known for intimate portraits of friends, often shot with a Polaroid camera. His gritty aesthetic highlighted the materiality of the photo itself since he had no problem writing in the margins of his photographs or otherwise manipulating a photograph’s surface. There had been nothing precious about Morrisroe’s life — he was raised by an alcoholic mother, never knew his father and hired himself out as a teenage prostitute to fund his films — and there was consequently nothing precious about his photographs.

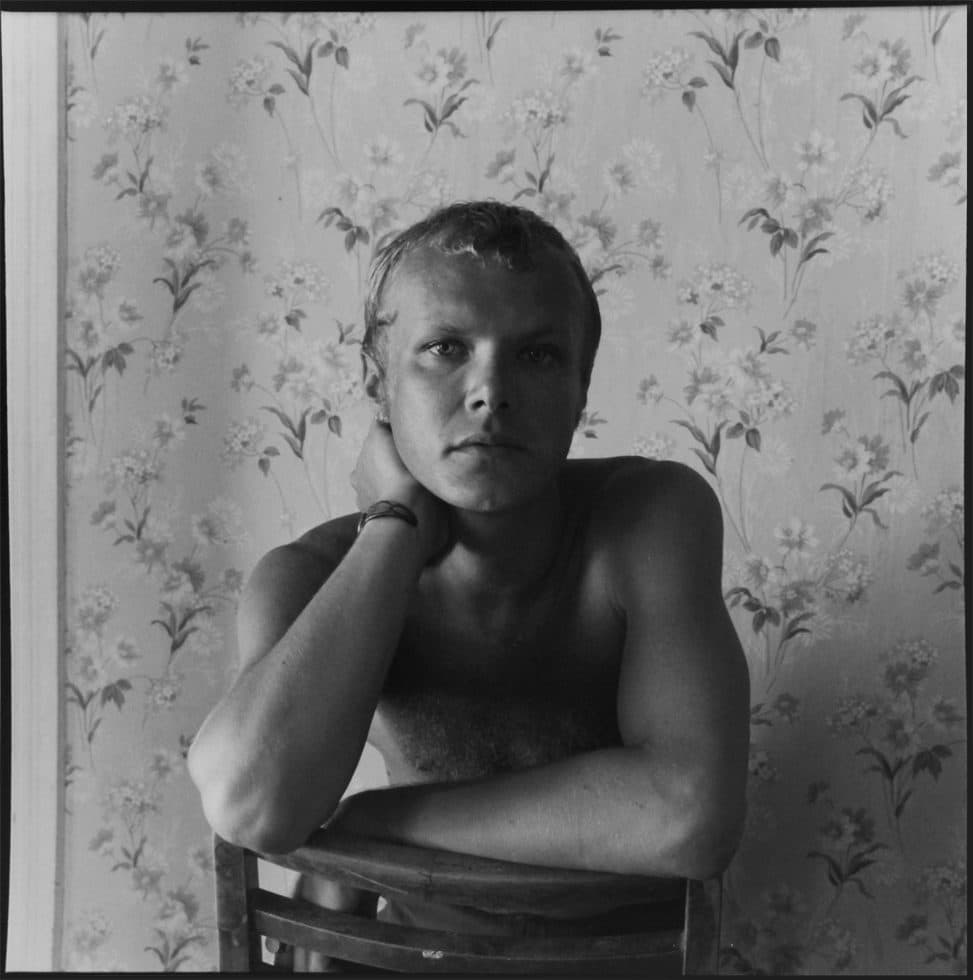

David Armstrong, who died in 2014 at the age of 60, became famous for his black-and-white close ups of good-looking young men, some of whom had been his lovers. His photographs chronicled the world of gay men, drug addicts, cross-dressers, artists and fashion models in portraits that were so emotionally raw they left the viewer a little ashamed for looking. After his years in Boston, Armstrong moved to New York where he became sought out by fashion designers looking to get their collections photographed in the same elegantly forthright style of his artistic work.

It’s tempting to compare these artists to an earlier photographer, Diane Arbus, who also documented marginalized “misfits” beginning in the 1950s and '60s, but Harrington says that may be the wrong comparison.

"The Boston School is much more interested in exploiting photographic techniques for performative ends," she says. "I see the rise (and ubiquity) of television as a progenitor much more than the work of photographers like Arbus. Much of the Boston School's work is more sensual, material and concerned with not only images but using images to self-fashion persona and community."

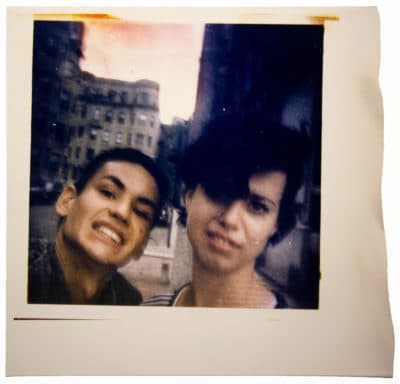

Included in the show is Morrisroe’s grainy color Polaroid of himself with artist Gail Thacker, another member of the Boston School known for similar Polaroid photography. The photo, taken in 1978 and manipulated again in 1986, is entitled “Blow Both of Us, Gail Thacker and Me, Summer” and was taken in what looks like the Fenway neighborhood. The color is a little off. The cropping is uneven. In one version of the photo, Morrisroe has scribbled in the margins. It was made using Morrisroe’s signature photographic technique of sandwiching two negatives together.

“Boston School artists of the late 1970s and 1980s benefited from access to emerging film and photography equipment through the Polaroid Foundation, MIT Film/Video Section or the Boston Film/Video Foundation,” says Harrington. “They were experimenting with this medium at a time of intense contradictions in Boston.”

These include, she says, the seediness of the Combat Zone (today’s Downtown Crossing and Chinatown area) which was giving way to increased development, a gay prostitution scandal involving Congressman Barney Frank, a thriving underground music scene and a looming AIDS crisis.

“That image encapsulates the exhibition,” says Cooney, referring to Morrisroe’s photo. “It’s kind of a little gritty. It's blurry. It's of he and a very close intimate friend.”

Boston, as always, is part of the story, as it was in countless other photos taken among this group, in nightclubs and bars, on street corners or even just at home in bed.

The in-your-face freshness of Morrisroe’s photograph stands apart from the kind of work David Armstrong did. One of Armstrong's photographs in the show is of a handsome, tanned man, shirtless, leaning on the back of a chair.

“The David Armstrong photograph is a much more staid and composed image,” says Smith. “It is his portrait of a friend in Provincetown and it's a very elegant kind of portrait of queer intimacy. Those are two poles of the exhibition in a way. There's a kind of brashness to a lot of the work, but there's also a deep quiet poetry to it as well. Those are two things that were happening concurrently, two threads that weave throughout a lot of the other work.”

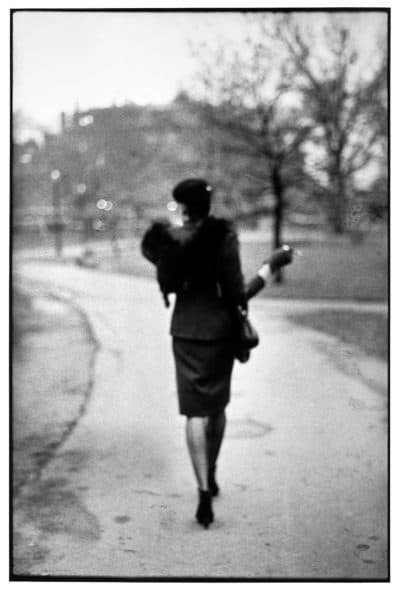

Meanwhile, Nan Goldin was shooting moody portraits of the people she liked to hang out with, often drag queens. In the show, her photograph “Ivy in the Garden” has a film noir quality that hints there is a lot more to come, and that a lot has already passed.

“She was just constantly photographing,” says Cooney. “There is that kind of casualness to some of the work that speaks even further to that intimacy, being with someone and knowing someone so well that you could just snap their picture at any time.”

Of course, artists like Goldin are now middle-aged and have become well-known for their work over the years, but “Under a Dismal Boston Skyline” doesn’t stop there. Since the 1980s, there have been plenty of artists working under the radar of the major institutions, following their own inspiration, doing their own thing despite high costs.

Two of the more recent Museum School grads in the show are Cobi Moules, a transgender artist who graduated with an MFA in 2010 and who now works in New York, and Creighton Baxter, a 2013 grad of the Museum School who now lives in Los Angeles.

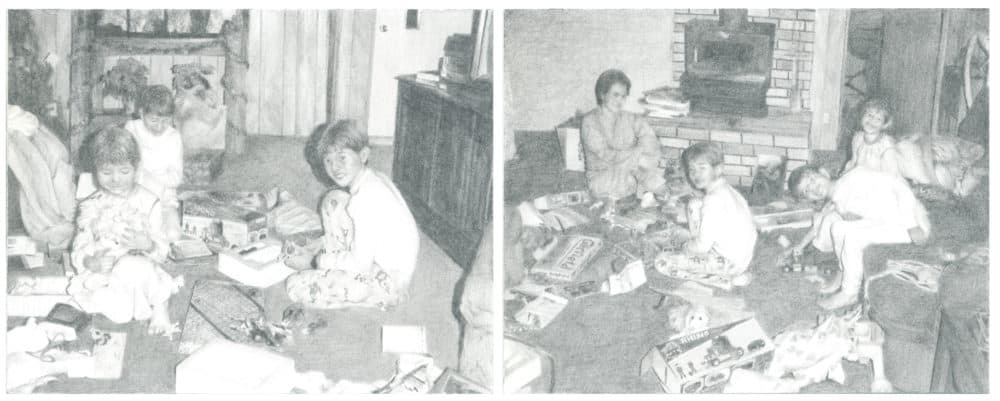

Moules’ work very much fits into the Boston school oeuvre — he does intimate drawings that are often self-portraits. This show features a drawing from his “Childhood” series — a 2011 drawing with a nostalgic snapshot quality that shows him unwrapping presents on Christmas morning with his family but with a male identity rather than female.

Creighton Baxter’s work is a drawing of herself that is part of her “Tidal” and “Until Niagara Falls” series. She says that the series of drawings, text and actions are about "trauma, sexualized violence and transmisogyny."

“I think the fact that Boston doesn't offer much of a fertile underground has encouraged this group of artists to create their lives and work on their own terms,” says Harrington. “Boston is a city of major institutions (in technology, medicine, academia, and culture), and those institutions sometimes cast too wide a shadow on the city's artists. The artists in 'Under a Dismal Boston Skyline' are not only working outside this shadow, they are creating their own pliable identities and communities in spite of these institutions. If you want to make work that pushes the boundaries in Boston, you have to make your own rules to do it.”

"Under a Dismal Boston Skyline" runs from Sept. 14 to Oct. 28 at BU's Stone Gallery. The opening reception is on Thursday, Sept. 13 from 6-8 p.m.