Advertisement

At Urbano, An Artist Reflects On Displacement And Work

What happens when you’re forced to move from one town to another, one region to another, one country to another?

Among the very first problems is work. You need a job. And if, for some reason, you can’t find work, especially the work that you’ve always done and loved, you may find that you’ve lost more than a job — you’ve lost an identity.

“Work is an action that helps us to elaborate our identities,” says artist Constanza Aguirre. “For me, when people are displaced, they lose everything and their identity. What identifies humans if it's not your trade, your work, your labor?”

The idea of displacement, dehumanization and the possibility of reclaiming one’s humanity through labor is the theme of “Wandering in the Land of Oblivion,” now on view at Urbano, a community art space and gallery located in the Jamaica Plain Brewery Complex near Egleston Square. (Aguirre is currently an artist-in-residence and conducts a workshop with local teens at Urbano.)

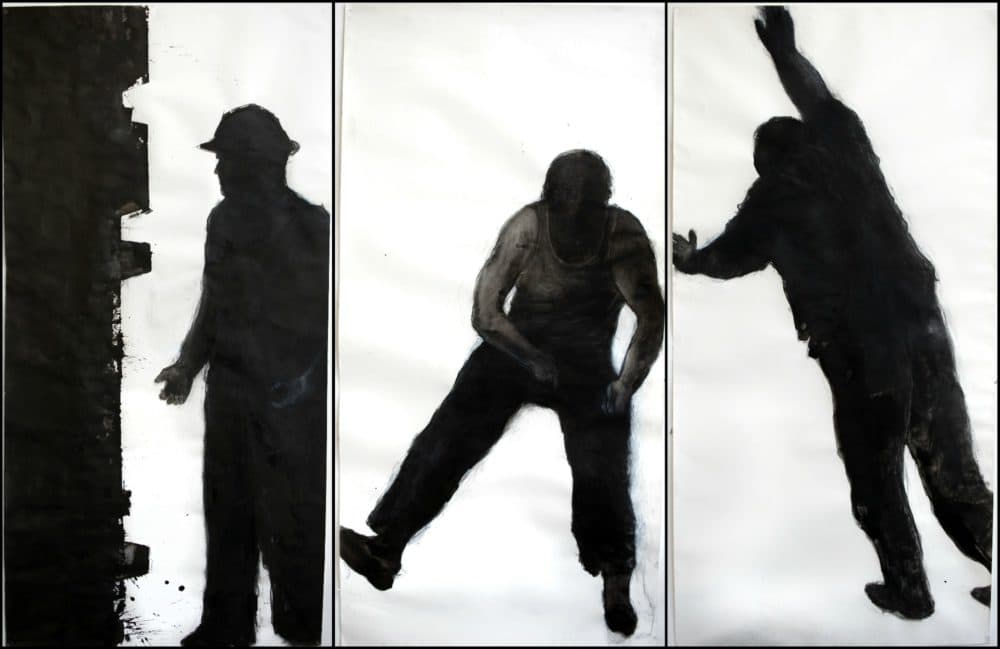

The exhibit of 15 large-scale black-and-white works on paper takes on themes that Aguirre, a Colombian-born School of the Museum of Fine Arts grad now based in Paris, has wrestled with for years. After witnessing the mass displacement of her fellow Colombians due to civil war, she began work on a trilogy of drawings and paintings examining the human condition, especially in relationship to displacement and violence. Past work in the series explored ideas revolving around the anonymous and “disappeared” in Colombia’s conflict as well as the mass movement of people due to unrest. These works, rendered in ink, charcoal and pastels, are a continuation of the trilogy but with a difference. There is hope here, the possibility of emancipation and reclamation of identity through the countless activities of work. These are our small acts of creation. And so, Aguirre has created stark drawings that feel monumental and powerful, while at the same time, poignant. We see the farm worker, the glass blower, the butcher, the sales vendor — all individuals who exert a certain amount of control in their daily lives through their industry, and who therefore also enjoy a measure of liberty. The drawings, though figurative, are loose and rough enough to have the feel of abstract expressionism.

“I am figurative, but I have a very strong part of me that is very abstract, very gestural,” Aguirre says. Intentional or not, her free drawings pick up on the “choreography of gestures” of the trades she depicts.

“What interests me in these paintings is more the gesture, the movement, than trying to describe the figure as a figure with a face,” she says. “The only thing that perhaps is more realistic is their hands.”

It was during numerous trips across Colombia that Aguirre says she had time to contemplate the consequences of mass displacement on Colombians moving from rural areas to large cities like Bogotá during the five decades in which the government and various guerrilla factions and crime syndicates violently wrestled for control. (In 2015, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported that 5,840,590 people were registered as being internally displaced in Colombia. In 2016, a peace agreement between the government and Colombia’s largest armed group promised a more peaceful future.)

“When I was traveling the country, I saw all these people that immigrate to the big cities,” says Aguirre. “In Bogotá, there are 1,500 people that each day came to the city to live because of displacement.”

She began to consider the long-term effect of displacement on the human psyche.

“For me, territory is a cultural place that is created by people with their work, with their history,” she says. “When they lose their territory, they lose everything. We lost our stories, our memories, family, everything. We lost even our condition as human beings, in a way. For me, work was the [re]construction of the territory. It was the most important thing to bring into this series because for me work is a gesture that [allows] me to be a human being.”

Urbano founder Stella Aguirre McGregor says Aguirre’s work fit neatly into this year’s larger theme at Urbano of “Resilience and Sustainability.” It is part of Urbano’s mission to regularly invite practicing professional artists to work with youth. Earlier this year, Urbano hosted artists David Buckley Borden and Nora Valdez who each led projects addressing resilience and sustainability with local teens. Although Aguirre happens to be McGregor’s sister, that’s not why she asked Aguirre to take time off from her role as artistic director at the International Lab for Popular Housing in Saint-Denis, France, to work with Boston teens. Rather, she says the work that Aguirre had been doing around displacement spoke profoundly to the possibility of resilience, even in the face of violence, dispossession, loss.

“I had seen her work a year or so ago when I went to visit her in Paris,” says McGregor. “I have a lot of respect for the mentoring Constanza has done with young people, so I thought it would be appropriate if she could work with youth elsewhere.”

And so, Aguirre has become the current artist-in-residence, conducting her own month-long workshop with teens from local public high schools, many of whom are from immigrant families. Since mid-October, Aguirre’s students have been creating work on the theme of labor, using the same limited palette that Aguirre uses but in other mediums. They are drawing, doing photography, collage, sculpture and even music composition. Their work will also be on display at Urbano at workshop’s end on Nov. 15.

Interestingly, Aguirre and McGregor have found that many of the American-born children of immigrants participating in the workshop have developed a negative attitude to work. They’ve noticed that immigrants have often been handed the toughest jobs with the lowest pay in the worst conditions. Work, for them, feels like exploitation more than a means to self-actualization.

“They don't look at work as a positive thing,” says Aguirre. “They are talking about the struggle between classes and the way they are already set by their condition, their condition of race, economic status, class.”

It has turned out, however, that in working with Aguirre, the students are coming around to another point of view. Maybe work can mean individuality, liberty, freedom, if they can find a way of working on their own terms.

“They’ve started to open a little bit and they’ve started to think they can work in a different way,” says Aguirre.

“Wandering in the Land of Oblivion” is on view at Urbano from Nov. 9 through Jan. 11, 2019. The gallery is located at 29 Germania St., Jamaica Plain. Gallery hours are 1-6 p.m., Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, and by appointment. To make an appointment, email info@urbanoproject.org or call (617) 983-1007.