Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

‘I Miss The Heck Out Of Him': A Year In, COVID-19 Has Killed More Than 200 Vermonters

Resume

It’s been almost exactly one year since Vermont’s first COVID-19 fatality. The virus has killed more than 200 Vermonters so far. The death toll in the state is small compared to most others, but the loss of each person ripples out through their family, friends and community.

To better understand the Vermonters who died, VPR reached out to the families of many of the fallen. Here are some of their stories.

Around 5 a.m. on March 19, 2020 Holly Barrett-Willard called the nursing home where her great-aunt, Betty LaBombard, lived. The 95-year old was struggling to breathe.

“She was on oxygen, but they didn't think she'd make it through the day,” Barrett-Willard told VPR in March 2020.

Barrett-Willard rushed over to Burlington Health and Rehab. “I sat with her and held her hand, I put lotion on her arms and washed her face, combed her hair,” she said.

LaBombard lived in Burlington her whole life. She spent decades as a waitress at Woolworths. She taught catechism. At 11 a.m. on that March day, she died due to COVID-19 — the first pandemic fatality recorded in Vermont.

Just three hours later, there was another one: 93-year old Robert Kirkbride. He lived in Ludlow and served in both World War II and the Korean War.

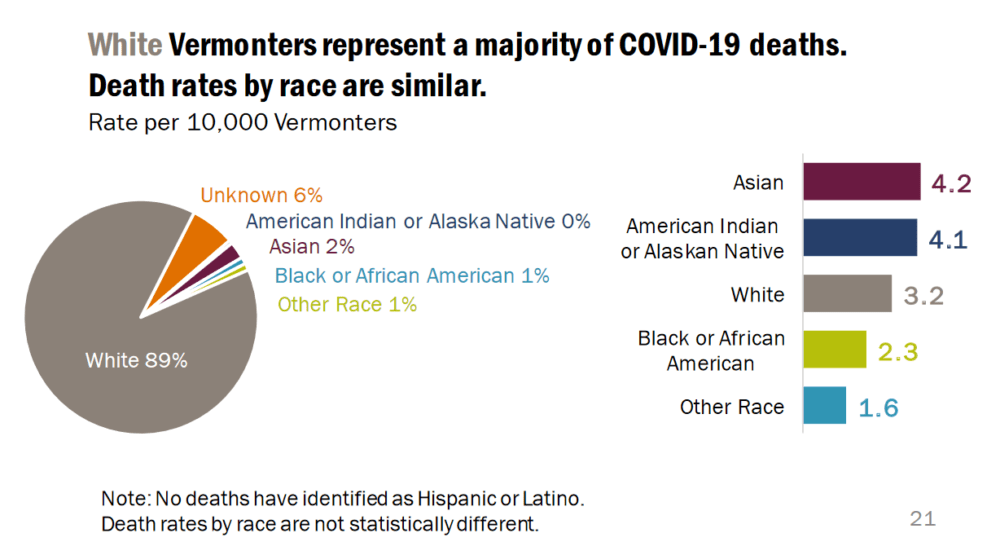

The pandemic has killed 214 people in Vermont in the past year. Almost 90% of those who died were above the age of 70; 52% lived in long-term care facilities; 70% didn’t have college degrees.

But those numbers don’t tell you that Burlington’s Leona Gutwin taught herself to paint flowers. The statistics can’t capture how much St. Albans’ David Reissig loved University of Vermont basketball. The data doesn’t say how many voicemails, like this one, Essex Junction’s Marilyn Hesford left her son:

“Hi Jack, it’s me, I found my glasses,” Marilyn says. She pauses, and then, in a conspiratorial whisper, reveals the hiding place: “They were in my pocketbook. Just thought I’d let you know. Love ya. Bye-bye.”

Nationally, the coronavirus has killed more than half a million people. Vermont has had the fewest fatalities of any state and its death rate has been one of the lowest in the country.

But the pandemic has still left thousands of Vermonters in mourning.

Naomi McCullough moved her family to Burlington on a whim in 1968 after seeing a picture of Lake Champlain in a magazine. The single mother of four was a nurse and spent her career working at psychiatric hospitals and nursing homes.

Her daughter Tommie Murray sometimes forgets she can’t call her mom anymore.

“I would call her just to figure out how to cook something, or if I was ticked off at somebody, or I got a new job or I bought something,” she said.

McCullough caught COVID-19 during an outbreak at Birchwood Terrace, a nursing home in Burlington. She died on April 11 at the age of 89. Birchwood was the site of one of Vermont’s first major coronavirus outbreaks.

It was also one of the deadliest — 20 residents died at the facility in Burlington's New North End.

The pandemic killed 56 people in March and April. But for the next six months, Vermont only reported five coronavirus fatalities.

“When we got that far into it, we had like this big sigh of relief that, ‘OK, she's made it this far,’ ” Erika Smith said. Her mom, Deborah Conrad, was living at Berlin Health and Rehab. Like many Vermonters with family in nursing homes, Smith hadn’t seen her mom for months.

“And then we got the call that she was COVID positive,” Smith said.

In November, the virus surged and people started to die again. COVID-19 killed 104 Vermonters in the final two months of 2020, just as the federal regulators approved vaccines. Many deaths occurred at long-term care facilities that were first in line for the shots.

Smith’s mom didn’t appear to have symptoms, but her health quickly deteriorated. Smith said it took a couple of staffers at the nursing home to help her mom remain upright.

“She couldn't sit up, she couldn't hold her head up, she couldn't communicate,” she said.

The day after Christmas, Smith and her brother stood in a snowbank outside their mother’s window.

“We could hear her gasping and we hoped that she could hear our voices,” she said.

Conrad died that evening. She was 70.

The isolation of the pandemic has compounded the loss felt by families. People were unable to hug or hold a loved one for a final time. Funerals were delayed, canceled or held virtually.

Bob Burdo, a life-long Burlingtonian, spent nearly 25 years as a custodian in the city’s school district. He was a devoted fan of the New York Yankees and loved to have his family over for cookouts.

His daughter Dawn Burdo has felt lost since her dad died.

“My hope is someday I'm going to wake up and know exactly what to do about that,” she said. “But right now, I have no clue.”

Janice Dunster has also struggled to adjust after losing her husband Melvin.

They met when they were teenagers. Melvin lived in Waterbury and would drive down about 10 miles to visit her in Moretown.

“After he came there that one time, he kept coming a while and then we decided, let's get married, Dunster said.

Melvin and Janice were supposed to celebrate their 68th wedding anniversary in August. But in July they both caught COVID-19 and were hospitalized. She recovered. Melvin died on July 28. He was 87.

“It’s horrible to know that you haven't got somebody that you've had so many years,” she said. “We had a long life together, but … I miss the heck out of him, really do.”

Melvin’s ashes sit in a container on the mantle in their living room. In that box is another compartment. Janice says when she dies, one day long after the pandemic has receded, that’s where she’ll end up — next to him.

This story is a production of New England News Collaborative. It was originally published by Vermont Public Radio on March 15, 2021. VPR Digital producer Abagael Giles produced the infographics for this story.

This segment aired on March 16, 2021.