Advertisement

As health care breaks down in Massachusetts, patients die waiting for care

Resume

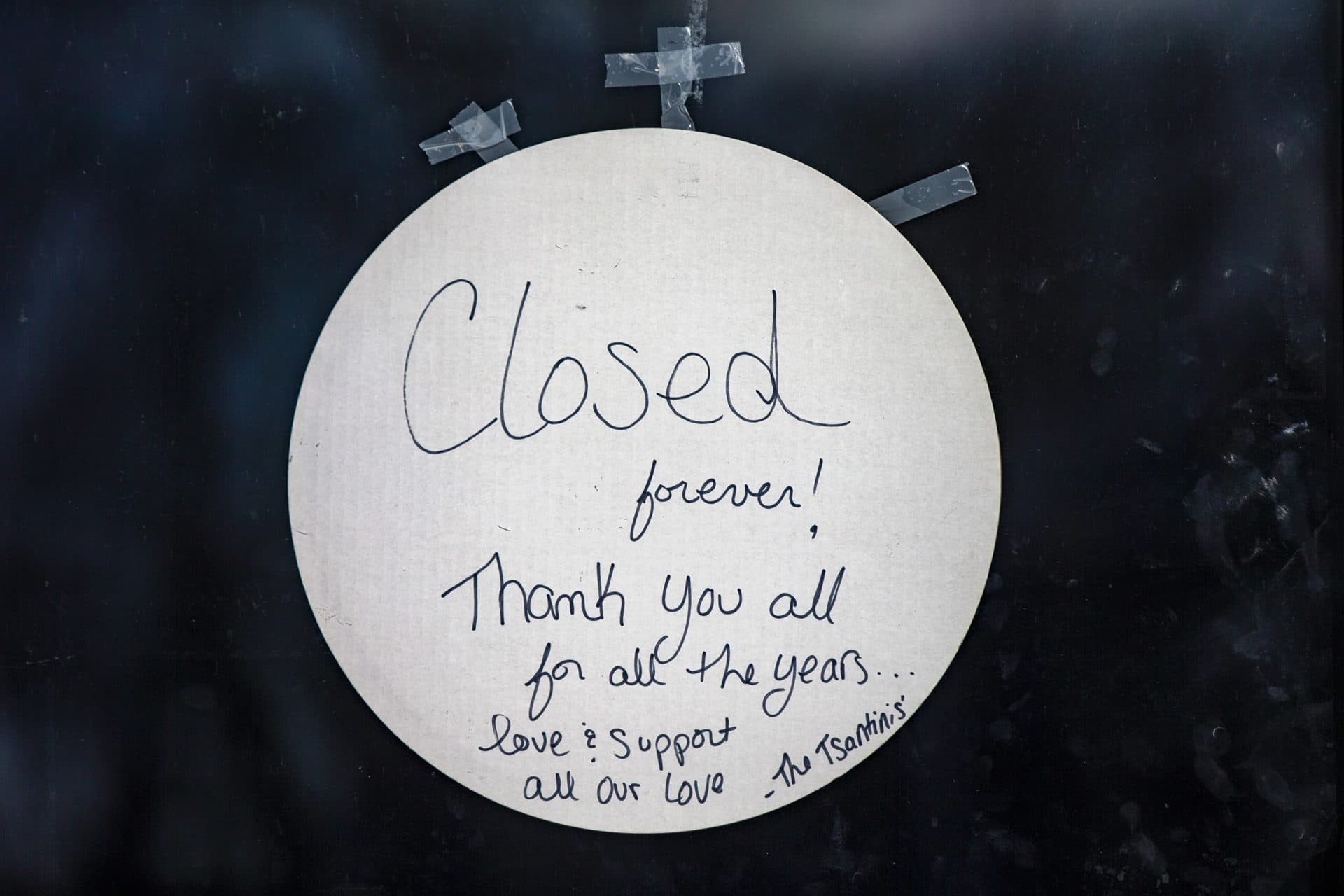

Fans of Athens Pizza in Brimfield learned the restaurant’s beloved owner was sick via Facebook.

“The pizza will be closed for the rest of the week,” reads the post from Nov. 30, 2021. “Unfortunately we have been exposed to Covid.”

Get well wishes poured in, but Athens Pizza will not reopen. Tony Tsantinis, 68, died at Harrington Hospital on Dec. 10.

His daughter, Rona Tsantinis-Roy is haunted by many moments from her father’s brief battle with COVID. Here’s one. As a doctor delivered the news that Tsantinis was dead, he “literally looked me in the eyes and said this didn’t have to happen,” Tsantinis-Roy recounted.

She understood that to mean that her father might have survived if he’d been transferred to a larger hospital. Typically, that’s what happens when a patient who arrives at a community hospital needs more specialized care. But with hospitals full — or close to it — across Massachusetts, transfers are harder and harder to arrange. And some patients are dying while they wait.

For Tsantinis, the hospital made two transfer attempts. As Tsantinis-Roy tells it, the first was on day four in the hospital as her father grew worse and needed intensive care. The ICU at Harrington was full, so doctors and nurses searched for an available bed at another facility. Tsantinis-Roy says they called 17 hospitals but couldn’t find an ICU that would take her dad.

Within a few days, Tsantinis-Roy learned that a bed had opened in Harrington’s ICU, and her father had been moved. But then his kidneys started to fail, and Harrington wasn’t able to provide dialysis. Hospitals say nurses who specialize in dialysis are in particularly short supply right now.

Harrington, in south central Massachusetts, again tried to transfer Tsantinis, but it was too late. A few hours before Tsantinis died, his daughter heard that Hartford Hospital would put him on its waiting list. But by then, Tsantinis was too unstable to make the journey.

"Everybody wants to believe that the system is holding up just fine, but it isn’t. It’s breaking down. And when it breaks down, patients are harmed."

Dr. Eric Dickson, CEO and president of UMass Memorial Health

Harrington Hospital says it won’t discuss the details of Tsantinis’s case. The hospital is part of UMass Memorial Health, which also declined to answer specific questions about Tsantinis. But the network’s president and CEO, Dr. Eric Dickson, says there are problems at every level of care patients need right now.

“Everybody wants to believe that the system is holding up just fine, but it isn’t,” Dickson says. “It’s breaking down. And when it breaks down, patients are harmed.”

The Baker administration responded to a request for an interview with an email containing bullet points about activating members of the National Guard to help staff health care facilities and helping to organize daily, regional calls with hospitals. The calls are supposed to promote collaboration between hospitals, balance the patient load and flag urgent cases. Tony Tsantinis’s death suggests this system is not enough.

Some hospital staff say it’s time to impose crisis standards of care, a set of guidelines that help determine who receives care when the medical system is so overwhelmed by a crisis, doctors and nurses can’t care for everyone. These standards were drafted by hospital leaders and patient advocates early in the pandemic. If access to ICU beds or dialysis is limited, for example, these guidelines would help hospitals determine who gets that care based on who is most likely to survive.

There are some concerns about using the guidelines now. Despite revisions, they may still give white patients with no medical or physical challenges easier access to limited medical resources. And they were drafted when the focus was on too few ICU beds and ventilators. Now, there are many more shortages throughout hospitals, including staff.

“It’s not as simple as not enough ventilators or ICU beds; it’s now a much more complicated environment compared to two years ago,” says Dr. Michael Wagner, the chief physician executive at Wellforce, who co-chaired the state’s Crisis Standards of Care Advisory Committee.

Wagner says the guidelines may need to be amended to address this surge. Even if they are, Dickson says asking hospitals to start using the crisis standards right now would impose undue stress on exhausted staff.

“We have to have a conversation among health care leaders and the state about what that would mean and how we would implement it,” he says. “But at some level care is already being rationed, because we don’t have the beds we need to take care of the patients who are coming in with COVID right now."

It’s almost like a lottery for care, and Tsantinis isn’t the only possible victim. At hospitals north and south of Boston, doctors describe patients who’ve died while waiting to be transferred for more specialized care: A gunshot victim and a man with heart failure are among them. A woman who needed surgery to stop a stroke waited eight hours before she was transferred to a stroke center; the ER staff that sent her don’t know if she survived.

Hospital employees did not have permission to discuss the details of these cases, but here’s one fact they can share: They all happened before omicron pushed hospitalizations through the roof. Dr. Kathleen Kerrigan, president of the Massachusetts College of Emergency Physicians, says it’s become even harder to transfer patients since mid-December when Tsantinis died.

“Dramatically,” Kerrigan says. "We’re hearing stories of 30 phone calls, trying to get patients, even out of state, to get the care that they need.”

Kerrigan’s members say it’s virtually impossible to transfer a patient into Boston this week, and now some hospitals in neighboring states are so full they are closing to out-of-state transfers. And the omicron surge has not peaked for hospitals.

“This was the pandemic we were afraid of when the governor shut down the state back in March of 2020,” Kerrigan says.

"This was the pandemic we were afraid of when the governor shut down the state back in March of 2020."

Dr. Kathleen Kerrigan, president of the Massachusetts College of Emergency Physicians

Which translates to fear that more families like Rona Tsantinis-Roy and her children will lose beloved parents and grandparents. Tony Tsantinis was able to call once, from the hospital. His daughter says she put him on speaker so he could talk to her kids. He assured them he’d be home soon.

“He said, ‘I’m good, I’m great, I love you guys,’ ” Tsantinis-Roy says. “He hung up with them, and obviously they were over the moon.”

But to Tsantinis-Roy, her dad’s optimism seemed too good to be true.

“We never heard from him again after that,” she says. “It felt like a goodbye.”

Tsantinis-Roy is still struggling to understand how her dad’s death could have happened in a state with health care that is supposed to be among the finest in the world. Dr. Melisa Lai-Becker, who runs the emergency room at CHA Everett, shares that sense of dismay.

“This feels completely surreal,” she says. “I’m practicing within spitting distance of at least five world-class medical centers in Boston, Massachusetts, which is considered one of the world’s medical meccas … and yet they’ve often had to refuse to accept these patients.”

This segment aired on January 14, 2022.