Advertisement

Heat, sewer problems and less lobster: New report details climate change's impact in Boston

Climate change will likely bring more hot weather and heat deaths to the Greater Boston area over the coming decades, as well as wrecked septic systems, more rain, fewer lobsters and cranberries, threats to drinking water, and more flooding on Morrissey Boulevard.

None of these findings, from a new UMass Boston report released Wednesday, are surprising. But the report provides an unprecedented level of detail on what to expect as the climate changes over the coming decades. Updated and expanded from the 2016 BRAG report to include 101 cities and towns around Boston, it looks at projected changes to temperature, storms, flooding, sea-level rise and groundwater.

"This report is part of a consistent drumbeat of evidence at the local, regional, national and international levels showing the urgency of climate action," said Sanjay Seth, climate resilience program manager for the city of Boston. Seth did not contribute research to the report, but will use it to help guide Boston's climate adaptation plans. "What residents are seeing already is real, whether it's hotter summers, whether it's the storms that we're seeing, whether it's changes in weather patterns in general, folks are really getting that climate change is a critical issue for them."

Here are seven takeaways from the report:

It's getting hotter. And you're gonna feel it.

The average daily temperature in Suffolk County will increase about 2.5-3℉ by 2040 even if we stop using fossil fuels today. And it could increase up to 9℉ by the end of the century if we continue business as usual.

"So what?" you might say. "In Massachusetts, the weather can change by more than 9℉ over an afternoon."

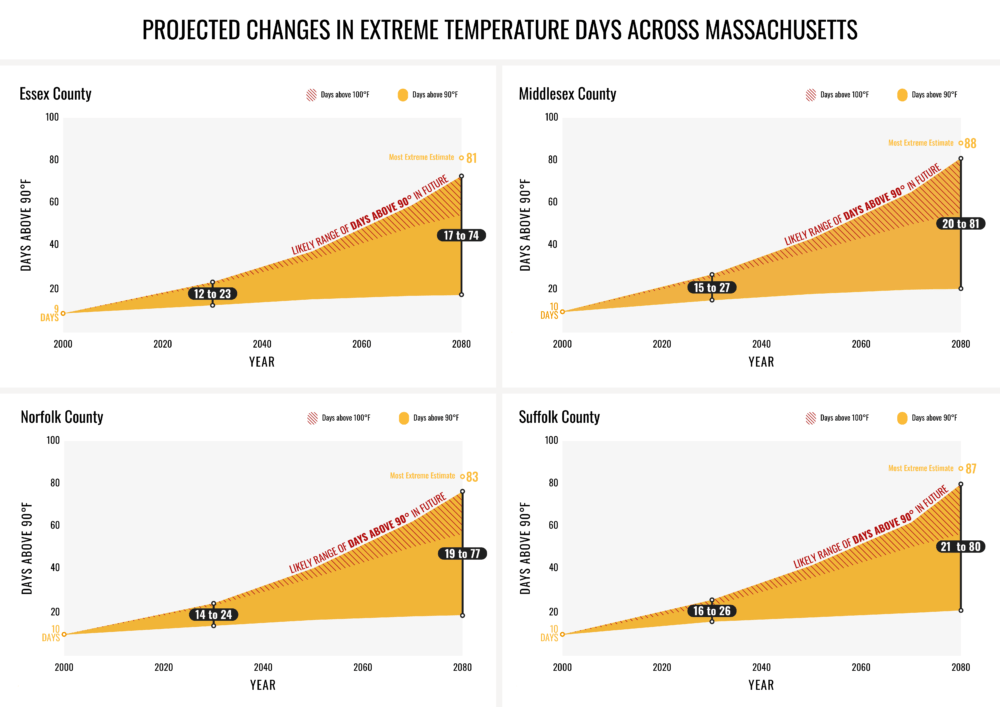

And it's true — the average yearly temperature increases don't look like that big a deal, but the extremes are worrisome. Right now, the region gets about eight or nine days over 90℉ each year; by the end of the century, that will likely be closer to 60 days, and could be 80 days or more. That's two months — or more — over 90℉ each year.

"When you have three or four or five days of temperatures over 90 or 95, the buildings are absorbing heat, the pavement is absorbing heat and it's not cooling down at night," said Ellen Douglas, a professor at the School for the Environment at UMass Boston and one of the lead authors on the report. Cooling systems can't keep up, she says. "We're just going to experience climate extremes that New England wasn't built for."

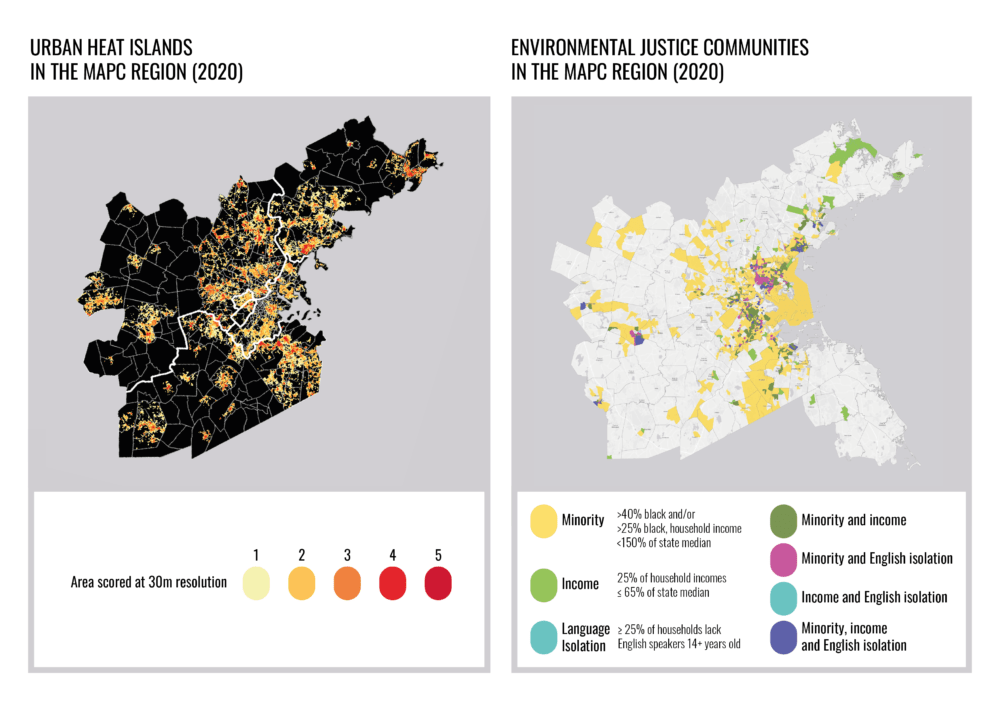

Traditionally underserved, marginalized and at-risk communities will get hit hardest, especially people living in urban heat islands with little tree cover. Some cities and towns, like Chelsea, are already experimenting with solutions like white roofs and "cool blocks."

"The people who are already overburdened today are going to be facing even more significant risks in the future," said Seth, "because heat is one of those things that really affects those who are elderly, those who are young, those who are unhoused or have illnesses."

Social justice is a huge component of climate change adaptation, said Paul Kirshen, a professor at the School for the Environment at UMass Boston, and one of the lead authors on the report. And it needs to be factored in explicitly.

These extremes can also lead to infrastructure problems, like crumbling concrete and buckling train rails. More heat will also cause losses in some of the state's traditional products, like cranberries and maple syrup; warming waters are already affecting the fishing industry, as lobsters and other local fish move north.

There will be fewer, but bigger hurricanes.

There will probably be fewer hurricanes hitting the area! But the ones that do hit will likely be stronger, since the proportion of category 4 and 5 storms will increase.

Since warmer air holds more water, hurricanes will also drop more rain on us.

On the upside, there will likely be fewer nor'easters, and those that hit Boston will be less intense and carry less snow.

We'll see less snow and heavier rain.

There will be less snow overall, but when it does snow we're more likely to get whacked. Extreme precipitation — fast, heavy rain or snow — has increased in recent decades and will keep rising.

The report predicts a 10-20% increase in daily precipitation intensity by 2050; 20-30% increase by 2100. Those projections haven't changed a lot in recent years, said Douglas. However, the numbers are no longer considered conservative.

Heavier rain will strain Boston's stormwater infrastructure, which is designed to handle about 5 inches of rain in 24 hours. We could be seeing more than 6 inches in 24 hours by the end of the century, said Kirshen.

"So all of our stormwater management, which is responsible for preventing streets from flooding, basements from flooding, is now out of design and is not functional," he said. "Groups like Boston Water and Sewer Commission have got to figure out how they're going to handle that extra water. There's ways of doing that. It's expensive, but it can be done."

Drinking water may get scarce (or salty) in some towns.

Many cities and towns around Boston get water from the Quabbin and other surface reservoirs. But 31 rely solely on local wells for drinking water, and these groundwater supplies will grow more stressed as the climate changes.

Groundwater is the water stored underground in the soil's "saturated zone," typically 8 to 20 feet below the surface. The top of this zone is called the water table. In Massachusetts, groundwater gets "recharged" during rainstorms and when snow melts in the spring.

But climate change will disrupt this pattern: less snow and more heat means less water seeping deep into the ground. And more intense rainstorms won't help: there's a limit to how much rain the soil can absorb at one time.

"It's kind of a double whammy," Douglas said. "More of the rain we're getting happens at such a fast rate that it can't infiltrate. And then the temperature is so much higher that anything that does infiltrate gets evaporated quicker. And over time, that means less groundwater available for drinking water and ecosystems."

Some towns that rely on local wells for drinking water have already seen their systems strained due to climate change and population growth, said Martin Pillsbury, director of environmental planning for the Metropolitan Area Planning Council. "A few towns have actually retired their wells and connected to the MWRA water system or other water systems to replace those wells because it was becoming so challenging," he said. But that's not cheap, and not an option for all towns.

Coastal areas — up to three miles inland — will see different groundwater problems. Rising seas will push salt water into wells, affecting drinking water quality. The rising groundwater could also damage septic systems, and other waste management sites located along the coast.

Sea-level rise may be lower than originally projected.

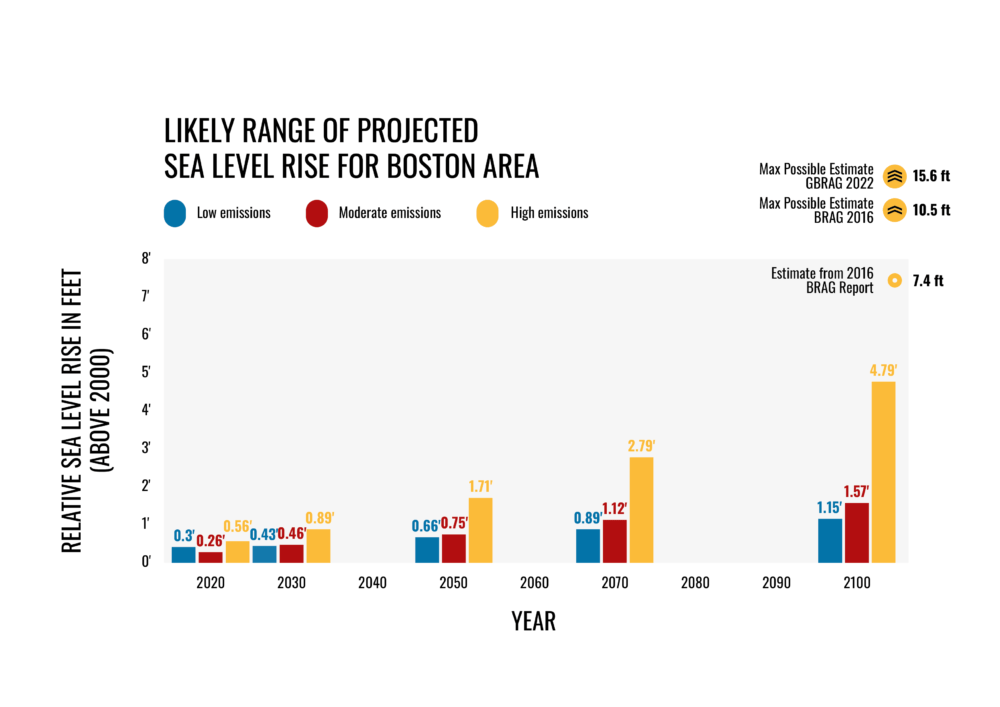

The new report projects a lower sea-level rise for Boston Harbor than the 2016 report: 4.8 feet by 2100 under a high emissions scenario instead of 7.4 feet.

"The difference is because of better understanding of the phenomenon of sea-level rise," said Kirshen.

Kirshen points out, however, that 4.8 feet is the most likely number; we could still see more than 15 feet of sea-level rise by the end of the century, depending on how the ice sheets melt in Greenland and Antarctica. He also noted that Boston has one of the highest sea-level-rise rates in the world, partly because the land is sinking about six inches every hundred years as it continues to adjust from the last ice age. Thanks a lot, glaciers!

Higher seas will also lead to more 'nuisance flooding.'

Despite the lower end-of-century projections, Boston will see more "nuisance" or high-tide flooding, when the local flood threshold is exceeded for at least an hour. Right now, Boston usually experiences less than 15 days of nuisance flooding each year. By 2050, nuisance flooding may occur on roughly half the days each year. That means Morrissey Boulevard could be underwater every other day.

"Half of the days! That's a lot. That means every other day we don't get to go to UMass Boston," said Douglas. "We've crossed a threshold when it comes to nuisance flooding."

Douglas noted that there's a movement to start calling nuisance flooding "disruptive flooding," because of serious impacts to traffic and infrastructure.

Even though things look grim, it's still worth trying to get emissions down.

"It's really important that we do try to get to net zero emissions by 2050," said Kirshen. "If we do, we may only have a foot of sea-level rise by end of the century."

While a foot of sea-level rise is no picnic, it's a lot easier to manage than 5, 10 or 15 feet, he says. And what we do know will determine where we end up in 2100.

"What [the report] shows to me is that we have a window to address climate change," said Seth, Boston's climate resiliency program manager. "We have a window to prepare our cities for the effects that are unavoidable. But there is no world in which we have cities that can thrive if we don't address climate change with a significant sense of urgency."

This article was originally published on June 01, 2022.