Advertisement

NFL Owners, Players Still Talking

Resume

The National Football League and the NFL Players Association continue to operate in a way that would have driven Cinderella nuts.On the deadline front in their negotiations, midnight Thursday night turned into midnight Friday night, and late Friday afternoon, that became midnight next Friday.

For football fans, the good news is that the two sides have not yet allowed the clock to strike twelve. They've provided themselves with additional time to reach an agreement that would avoid a lockout, a development that might delay the start of the 2011 NFL season, or even put that whole campaign in jeopardy.

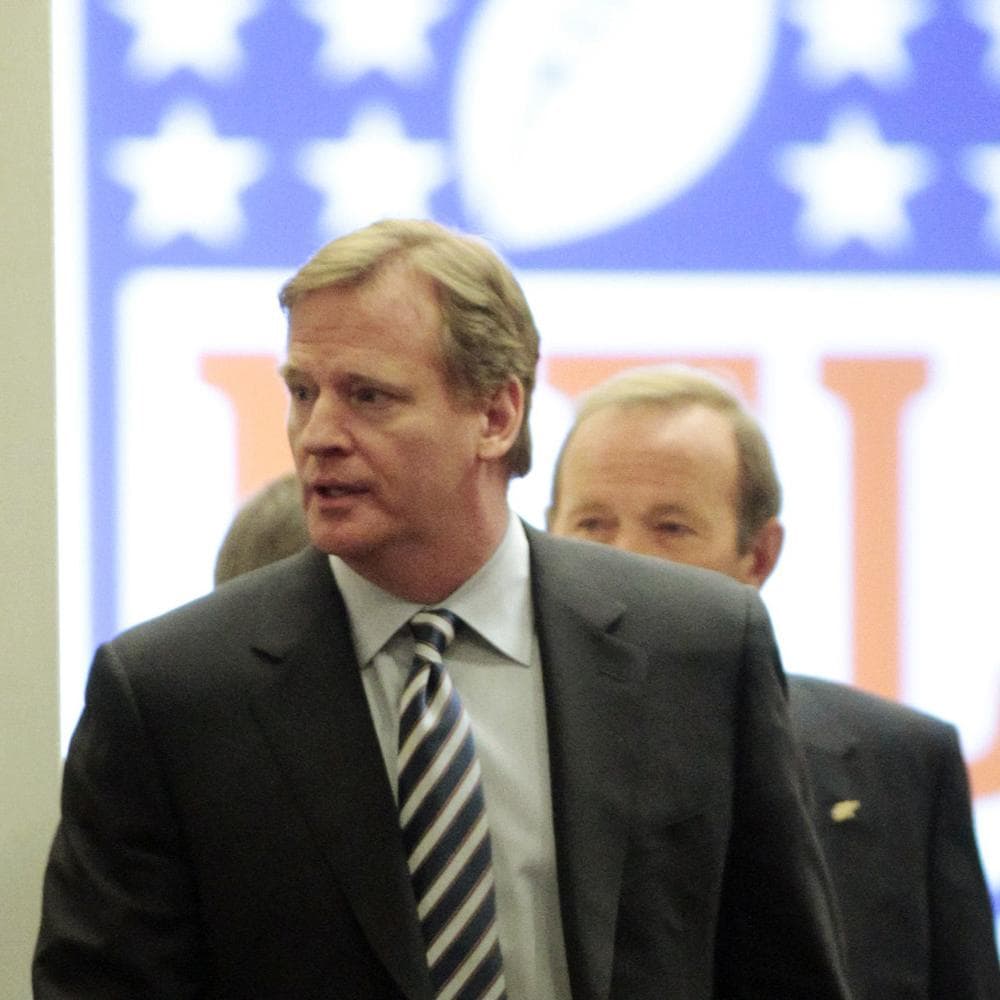

The bad news is that there is still no agreement. According to Gary Roberts, Dean of the Indiana University Law School at Indianapolis, that's partly because the principal representatives of the two sides, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and Players Association Head DeMaurice Smith, have each promised a good deal to their constituencies.

"Goodell promised that he was going to take back all the concessions that Paul Tagliabue gave in 2006, and DeMaurice Smith promised the players and agents that he was going to hold on and not give anything back," Roberts said. "They sort of painted themselves into a political corner, and can't really make compromises or concessions this early in the game. That's why I think we're sort of at loggerheads, and why I've predicted you're not going to see a deal done until August or September."

The personalities come and go in negotiations of this sort. A lot of the issues remain the same. Here's one most people familiar with collective bargaining will recognize right away: money. The NFL generates about nine billion dollars a year. The owners currently get to swallow the first billion before they have to start sharing money with the players. These owners want the second billion as well. The players would prefer not to lose a share of that second billion. According to Vermont Law School Sports Law Professor Michael McCann, that's not quite to suggest that there are no other matters for debate.

"For instance," he said, "the owners want to add two games to the regular season. Then there's the player conduct policy that Commissioner Goodell of the NFL wants to implement. But the key issue is money. The players don't want to take a pay cut, which is the way they see the owners' offer. The owners, though, insist that, given the economic circumstances and given that up to 90 percent of revenue is shared among the teams, concessions have to be made."

The failure of the two sides to reach an agreement has inevitably led to charges of recalcitrance from both camps. Professor James Gross of Cornell Law School feels that recent developments in the bargaining cast doubt on those charges:

"It's clear that hard bargaining is going on, but I don't see any evidence that the owners are trying to bust the union, or deny them their collective bargaining rights," he said. "I think the fact that you have further extensions indicates that there's some good faith involved here, and I don't see any evidence of attempts to bust the union."

Since the negotiations are occurring while organized labor and the right to bargain collectively are under attack in Wisconsin and elsewhere, some observers have lumped the struggle of the NFL players with the struggles of teachers, state and municipal employees, and various other workers trying to assert their traditional rights. James Gross feels that's inappropriate and inaccurate:

"I consider what's going on in Wisconsin as the attempt to deny people their right to engage in collective bargaining, which I consider to be a human right," he said. "The NFL negotiations pale in comparison to that."

That's not to suggest that negotiations regarding football players are not significant. Pro football is not only a nine billion dollar a year business that employs tens of thousands of people to do the hundreds of tasks required to produce games. It is also the country's most popular sport. Those who depend on the game for their livelihoods, and those who just enjoy watching it each weekend and perhaps even betting on it, certainly hope that the tone of next week's second extension of the bargaining period will be more productive. Professor Michael McCann, for one, feels that's likely.

"I think there's a shot," he said. "I think some of the rhetoric will be toned down. I think there's now recognition on the part of both sides that they're getting to the point where if neither side blinks, then they're both going to be worse off. When push comes to shove, there's going to be a strong impetus on both ends to get a deal done, even if neither side is really happy about it."

The alternatives to that outcome are nasty to contemplate. If the players union concludes that the NFL is not bargaining in good faith, the players could elect to decertify their own union, which, according to Professor McCann, would inevitably invite the courts into the ongoing misadventure.

"Desertification would mean that the NFL Players Association no longer represents the NFL players as a collective unit," he said. "And as a result, rules that have been collectively bargained between the association and the league would lose what's called the labor exemption. Without the labor exemption, many NFL rules, including the salary cap, would become subject to anti-trust law. So it's a pretty substantial move on the part of the players."

The owners can probably avoid that "substantial move" and the unpredictable legal wrangling it would provoke by scaling back their demands regarding that second billion dollars mentioned earlier, but those dollars aren't the only thing on the minds of the players, at least according to Izell Reese, who retired from the NFL in 2004. Reese feels the two additional regular season games the owners want would take a significant toll on the health of the players…and on matters like that, he's an expert.

"I had neck surgery," Reese told me. "I have nerve damage in my left shoulder. I can't tell you how many concussions I've had, and how many fingers I've dislocated over the years, but I won't really feel the effects of all that until I get older. I'm 36 now, so until I'm 46, 56. Yet my health benefits [ceased] five years after my retirement."

Unless the current negotiations improve upon that benefit, today's players, like Izell Reese, may be on the hook for whatever medical expenses they incur after they've been out of the NFL for five years, even if those expenses come as a direct result of their previous employment.

Izell Reese and lots of other current and former players, folks employed by the NFL and the teams, and millions of fans will be watching this week to see if the league and the players association can take advantage of the second overtime in bargaining.

This segment aired on March 5, 2011.