Advertisement

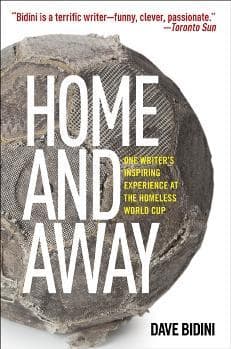

Home And Away

ResumeBill Littlefield's thoughts on Home And Away:

Dave Bidini's account of his trip to the 2008 Homeless World Cup in Melbourne is not only "inspiring," as the book's subtitle claims, it is funny, and it is weirdly optimistic.

Bidini describes the performance of one player "giving his team the lead the way a magician produces a bouquet of flowers out of nothing." Can you read that phrase without wanting to share it with somebody? I couldn't.

At a point during an impromptu gathering of homeless players, the participants begin singing songs of their homelands. The Poles sing, as do the Mexicans, the Dutch, and the New Zealanders, and eventually the Kenyans and South Africans, and Bidini writes: "To my ears, a stranger and more glorious cacophony had not been heard."

Since it began in 2003 with eighteen nations, the Homeless World Cup has grown into a larger and more inclusive event. Former players, who were former addicts, have become coaches. The event has moved around the world, and everywhere it has gone, as Dave Bidini puts it, the spectacle "has shown people that homeless men and women are part of the city, too."

Capitalist countries and socialist countries…rich countries and poor countries…countries that are relatively democratic and countries that are not…they all need to get better at taking care of their most unfortunate and damaged citizens. The first part of that development is the recognition that these folks are often "ignored or sneered at," as Dave Bidini puts it. The Homeless World Cup represents a modest but heartening effort at progress in that realm, and Bidini's account of his own experience with the Canadian team and the other participants at the 2008 event in Melbourne chronicles the encouraging occasion with grace and compassion.

An Excerpt From Home and Away:

I accepted Paul’s invitation and flew to Calgary for the national summer tournament.There, I walked into an argument between three homeless men stalking each other on the steps of the grey building that housed the event’s gymnasium and indoor soccer fields. First, Devon—a nearly toothless Jamaican Canadian who suffered from mental health and addiction issues—called Billy, the recovering OxyContin addict, a douchebag. Then Eric—the team’s goaltender, who moved about like a willow sagging after a long rain—called Devon a cocksucker. Then Devon chased Eric around the parking lot, hucking an orange at him and growling “Man, don’t call another man cocksucker.” Devon skulked behind the rear of the building, looking out occasionally to see if the goalie was coming back for more. But Eric had returned to his pre-championship pickup game, which is where the argument had started: Devon wanting to play, being rebuffed by Billy, swearing at Billy, then being sworn at before Eric called him a cocksucker, at which point Devon grabbed the orange, then a can of Coke, which slung inside Devon’s trouser pocket.

The Calgary tournament had been staged to give Paul, the manager, and Cristian, the coach, a chance to survey all of the homeless players in one fell swoop. While neither Devon nor Eric were eligible to play—they’d already competed for Canada in previous world tournaments; Homeless World Cup (hwc) rules stipulate that players can only represent their country once—the coaches were considering naming Billy to the national team, as well as Krystal, who’d recently moved in with her brother, Jason, in Toronto. After the argument played itself out, I went inside the gym, where I found Krystal sitting on a set of metal bleachers, eating a granola bar and staring at the court.

“I was adopted when I was two,” she told me from the stands. “My mom dropped me off at my brother’s friend’s house—his name was Soldier—and that was when Children’s Aid got involved and helped me find a home. I don’t know who my dad was, but I kept in contact with my mom and grandparents. Sometimes my adopted parents would drive me back to Regent Park to see my mom, and I remember being so excited going through the hallways of the building waiting to see her. My only two memories of her are the day I found out she’d died, and visiting her one time when she was standing in the doorway of the building telling me that she loved me. I didn’t really know what her life was about until years later. When I was 16, my grandmother gave me a box of letters that our social worker had written to my family, describing how my mother was a prostitute, how she was addicted to drugs, and that she’d died of aids as a result of being a sex worker in Regent Park. She’d been born in Trinidad and came to Canada, but because my grandfather lived in the States, she went back and forth from country to country. Things were bad where my grandpa was living, and she got drawn in, overwhelmed and tempted by things in the big city. There were rules at my grandma’s house, but not so much in the States. Sometimes I think that if I were a little bit older— that if I wasn’t just a baby when the problems started to happen— I might have been able to help her, to make a difference. If I could go back in time and change it, I would. But the way I look at it, everything happens for a reason. Maybe I’m able to do all of the things because she never got to. She’s in my heart. She’ll never leave me.”

We sat in silence for a moment as a few players began drifting onto the court. Then Krystal clasped her hands together and said, “I really hope the coaches choose me for the team. I mean, Australia. It would be my dream to go to Australia.” She paused and then she said: “Actually, it would be my dream to go anywhere in the world. But Australia. Man . . .”

At the end of the three-day event, Krystal made it easy for the coaches to select her. Before the tournament’s final game—which Toronto lost to Vancouver in a thrilling shootout (there were also teams from Calgary and a three-person representation from the Old Brewery mission in Montreal)— the players were asked to talk about their experiences in Calgary. Cristian—who, because he was young and track-suited, talked shit with the players, if in a tone measured with a smile—told them that if they had anything to say, now was

the time.

At first, they were quiet, but you could tell what they were thinking. By this point in the event, Eric, the goaltender—a tempestuous, six-foot-two crack addict whose gaunt face was drawn with the perpetual charcoal of a person too defeated to groom himself—had begun to wear on his teammates,and they’d frozen him out after the final game. During the meeting, he was the first to speak, telling his teammates in a

low voice how disappointed he was that they hadn’t congratulated him after many of the games. “Every other team does it,” he said. “The first thing they do is congratulate the goalie, but all you guys do is walk away.”

The players rolled their eyes. They may have been exasperated with Eric’s popgun temper, but the real issue was about more than just Eric. Their lives were so difficult and complicated that together those lives produced an entanglement of fear, self-doubt, sadness, neurosis, and anger, a powder keg of suffering that was defused only when the players were working together on the court. Once the games had ended, their endorphins flattened and their bodies—which had tasted a natural, physical high for the first time in ages—sought to continue the tourney’s competitive stimulation. The result was anger and revolt and confrontation. And really, because it had already been a huge struggle—and a great triumph—for these players to simply make their flight to Calgary, they lacked the emotional reserve to deal with the massive issues in each other’s lives. So when Eric bared his heart, there was little energy or impetus left to console him.

After Eric finished talking, the coach moved to send the team back to their hotel. But Krystal turned to her teammates and said, “Eric’s right, guys. No matter what happens in the game, we should go up and thank our goalie. We may not like what we have to put up with—and not just with Eric; we can all get on each other’s nerves—but we’re a team, and we should be able to count on each other all the time.”

Nobody else had anything else to say.

“I mean, it’s what teams do,” she added.

“So, you know, let’s start doing it.”

This segment aired on July 2, 2011.