Advertisement

111-Year-Old Diary Connects Two Turning Points In Football History

Resume

We’re going to start in 1905, a season that saw at least 18 college football players die.

"Football developed into this slugfest – and it really was a slugfest along the line of scrimmage," says sports historian Ronald A. Smith.

By 1905, football had already outlawed the sport’s most dangerous play, the flying wedge. But the game found other ways to kill its players. Smith says the most popular play called for the offense to simply smash into the defensive line and hope for the best. Beyond that, fighting was most definitely tolerated, if not allowed.

"At one time, you wouldn’t be booted out of the game unless you were called for three slugs," Smith says. "It was a brutal game."

Brutal enough to bring calls for the abolition of football, which got the attention of one football-loving resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

"The President of the United States, Teddy Roosevelt, got involved. He called Harvard, Yale and Princeton down to the White House to discuss the unethical play that was going on and the brutality that was going on," Smith says.

"The President discussed the question of foot ball in general and made a few remarks on unfair play," Harvard head coach Bill Reid wrote in his 1905 diary.

Ron Smith discovered Reid’s 440-page typewritten diary in the archives at Harvard and published it in a book called "Big-Time Football at Harvard, 1905" back in 1994.

"Mr. Roosevelt ... wanted to see if there was not some way in which the feeling between the colleges could be improved," Reid wrote.

But football wouldn’t change — at least not yet. And when change finally came the following year, Coach Reid would be instrumental.

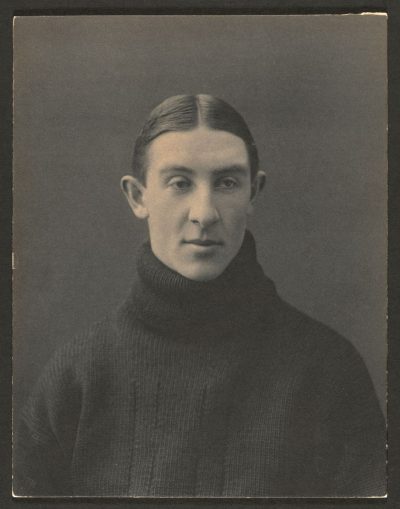

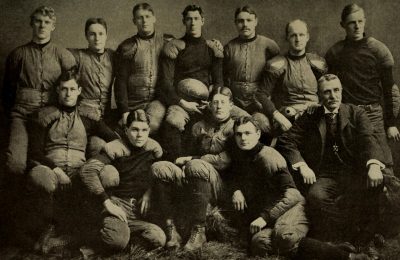

A Hero Returns To Harvard

As a Harvard sophomore back in 1898, Bill Reid scored two touchdowns against Yale. And then as a coach in 1901, he led Harvard to its first undefeated season. Reid went back home to California for a while, but in 1905, after Harvard failed to score a single touchdown in three years, Reid returned to Cambridge as the school’s one true hope.

"And he wrote this diary principally so that he and future coaches could know better how to beat Yale. That’s the only important game," Smith explains.

In order to beat Yale, Harvard would need to keep its players healthy through the last game of the season.

"Dr. Nichols will be medical advisor for the eleven, and is going to be a mighty valuable man there. Already he has made a quantity of first rate suggestions," Reid wrote in his diary.

And soon, the Harvard football team would get some medical advice that was 100 years ahead of its time.

Unexpected Discovery

It’s that advice that caught the eye of another former Harvard football player, Christopher Nowinski. The year was 2005, a whole century after Bill Reid wrote his diary, and Nowinski was in the middle of writing a book about sports and concussions. Dr. Bennet Omalu had only recently published his discovery of CTE in the brain of a deceased football player. Research was just getting started, so Nowinski didn’t have nearly as much to work with as he does today.

"My roommate was a former teammate of mine and he was a big Harvard football memorabilia buff. And he just happened to mention to me, ‘You know, you should check out that book to see what they thought about concussions back in 1905,'" Nowinski recalls. "And I told him, ‘You idiot, they didn’t talk about concussions back in 1905. I’m not going to find anything.’ But I was shocked to find that they talked about concussions throughout the book."

And then there was this: A speech given to the Harvard football team by Dr. Nichols. Here’s how Coach Reid remembered it.

"The next thing he said was that in case any man in any game got hurt by a hit on the head so that he did not realize what he was doing, his team mate should at once insist that time be called and that a doctor come onto the field to see what is the trouble."

Nowinski couldn’t believe what he was reading. After playing football at Harvard, he had become a pro wrestler. He suffered so many concussions that doctors told him he had permanent brain damage. He's at risk for developing CTE.

"And I thought, 'Wow, the team doctor gave a speech to the team that says, "Call a time out if you think your teammate has a concussion?"' I said, 'That’s weird, because I don’t remember ever getting that speech.'"

"I vividly remember in high school having teammates in the huddle that could not remember the plays, and it just never, never crossed my mind that that was a bad thing – that that wasn’t anything but a normal part of playing football.

"It made me realize that we’ve actually known about concussions for a really long time, and we actually respected concussions over 100 years ago."

"It made me realize that we’ve actually known about concussions for a really long time, and we actually respected concussions over 100 years ago. And now we were ignoring them, and we were getting guys who were knocked unconscious and putting them back in and saying they were tough."

This isn’t how things are supposed to go, Nowinski thought. We’re supposed to learn more about medicine as time goes on…not forget what we knew, right?

"At that point, I was uncovering what the NFL had been doing to bury the concussion issue and publish bad research and tell us that there’s no long-term effects. And I realized, “You know what? This is something a little more insidious here, you know, it’s not just that we forgot about this. There’s been a reason to forget about this, and it wasn’t in the interest of players, but it was in the interest of people trying to make money off the game."

There was less money in 1905, of course, but still…that’s pretty much the dilemma Coach Reid, Doctor Nichols and the Harvard football team wrestled with: would they put a player’s health first, even though it might cost them the most important game of the year?

Dan Hurley's Injury

The story of that dilemma began during Harvard’s second-to-last game of the season, on Saturday November 11, 1905.

"Dan Hurley was the captain of the football team and a halfback, and he got hit during the Dartmouth game," historian Ron Smith says. "And he was sort of...crazy."

That hit isn’t documented in Reid’s diary, though the coach did mention that after the game, Hurley sobbed uncontrollably about his poor performance.

But soon, it became clear that Hurley wasn’t quite himself.

"Dr. Nichols, the team physician, picked up on this and said, 'We better really take a close look at him. And don’t let him go into scrimmages where he might get hurt anymore.'"

On Thursday, three days before the Yale game, Hurley refused to eat anything other than a bowl of prunes for lunch and kept repeating the same two or three sentences over and over.

"Besides this he was late for lunch and I could not seem to impress on him the necessity of promptness," Coach Reid wrote.

Later that day, Hurley walked into the athletics office to get some tickets to the game. Then he asked if he could also have a bowl of crackers and milk.

Dr. Nichols drove Hurley to the hospital, where he was admitted. And Coach Reid told a gathering of Harvard supporters that their captain would not be available to play against Yale.

"A hush came over the whole room that was most impressive – it extended all through the building," he wrote.

Hundreds of Harvard fans took to the streets to sing in support of Dan Hurley. The team kept Hurley updated on the game via a special wire. Harvard lost, 6-0.

But what wasn’t well known – until Ron Smith published Coach Reid’s diary 90 years later – was the nature of Dan Hurley’s injury. Reid chose to hide the fact that his star player had a concussion, because he didn’t want it to be used as another reason to ban football.

But that’s not something that bothers Chris Nowinski.

"I mean, we still have people changing the public story about concussions for various strategic reasons or whatever, but, the fact is, he held the young man out. And that, I think, was what was most important. The doctor was allowed to give that speech, encouraged to give that speech, and the coach talked about it as if this is a good idea, you know. We want our players looking out for each other."

Spreading The Word

After publishing “Head Games” in 2006, Nowinski was instrumental in connecting the families of former NFL players with the scientists who could identify CTE. He co-founded the Concussion Legacy Foundation, which seeks to educate athletes on their risks. Recently, Nowinski was working on a new campaign built around being a good teammate and he realized the perfect message had already been written…111 years ago.

And so the Concussion Legacy Foundation asked coaches around the country to give Dr. Nichols’ speech – or one similar to it – to their athletes once a year. They call it Team Up, Speak Up day.

The first one was held on Sept. 13, and 150 organizations participated. More than 3 million football, hockey and rugby players heard the speech.

"People love this message," Nowinski says. "And people recognize that they weren’t giving this message. And they were pretty surprised, and they said, 'Whoa, this was 1905? We’re behind. All right, we’re in.'"

The speech is working for Nowinski, and it worked for the other principals in our story, too. In 1906, Coach Bill Reid convinced the rules committee to adopt the forward pass and other innovations that would make the game less dangerous.

And Harvard’s captain, Dan Hurley? By all accounts, he made a full recovery. He became a doctor and was a longstanding member of the surgical staff of Boston City Hospital.

That’s not necessarily the fate Chris Nowinski would have expected.

"It’s because Coach Reid and Dr. Nichols were looking out for him," he says. "If he had played in that Yale game, it would have been totally different."

If you’d like to know more about the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s “Team Up, Speak Up” day, visit their website here.

This segment aired on November 19, 2016.