Advertisement

NBA's Forgotten Co-Founder And The Shot Clock's True Origin Story

Resume

Danny Biasone was 83 years old on the day in 1992 when Sean Kirst, then a columnist for the Syracuse Post-Standard, came to visit him.

"Danny was this tiny, indomitable force," Kirst says. "And when I met him, he was two weeks before death. He was in his bowling alley, which had remained unchanged since the days when he owned the Nats."

Biasone owned the Syracuse Nationals from 1946 to 1963, and he owned that bowling alley back then, too. The story Kirst had heard — the story everyone had heard — was that after a game one night, Danny Biasone scribbled calculations on the back of a napkin at the bar of his bowling alley and invented the 24-second clock.

Kirst says Biasone never talked about the "clock." He always called it the "time."

"He said the game had become tedious, and no one wanted to watch it. Because if one team got up by 10 points, they'd just stall the ball for the rest of the game," Kirst says. "Danny said something had to change. You had to have a change in the time. So he never said, 'I came up with this idea.'"

Biasone didn’t have to say he came up with the idea. Legendary Celtics executive Red Auerbach said it for him.

"Danny Biasone invented the 24-second clock by himself, alone," Kirst quoted Auerbach as saying. "I was at the meeting when he introduced it. He should get all the credit in the world for it."

"So I wrote about that and I get a call out of the blue from a woman who was very upset, who says to me, you know, 'My husband was instrumental in creating the clock. And no one remembers him, and no one believes it,'" Kirst explains. "And she was so upset, I wondered if it was for real. Some of my colleagues said that she had called before, and people sort of, to put this harshly, people kind of wrote her off as a crackpot."

Ever since he was a kid, Kirst had studied early basketball history. So, the woman’s claims got his attention.

"I said, 'OK, Mrs. Ferris. I'll come out and talk to you,'" Kirst recalls. "So I go out to this house in North Syracuse where this really gracious, wonderful person greets me, tells me that her husband is dying of Huntington's and he can't speak for himself."

Leo Ferris had a fatal genetic disorder. Some have said it’s like dying of Alzheimer’s, ALS and Parkinson’s, all at the same time.

"She brings out a paper bag and says, 'Here's clippings.' And it's a paper grocery bag," Kirst says. "And I start going through it. And maybe a quarter of the way through, I pull out a newspaper that shows Leo Ferris with Ned Irish and these other giants of basketball in 1949 at the instant at which the NBA was created.

"It blew my doors off. It's like, 'Holy smokes.' And I had no clue.

"I apologized. I apologized on behalf of myself and I apologized on behalf of all of the basketball hierarchy that had forgotten her husband and had disregarded her. I said, 'You know, you're right. And we're gonna do something about this.'

"And this thing really became more than just journalism for me. It became a quest for justice, historic justice, for this remarkable family that had been totally overlooked, unfairly."

'My Uncle Leo Invented The Shot Clock'

Around the same time, nearly 2,000 miles away, Christian Figueroa was growing up in Puerto Rico. Like many of his friends, he loved playing and watching basketball. One day, before he was 10 years old …

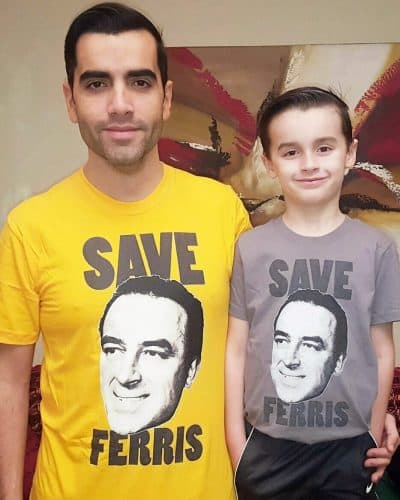

"I was watching a basketball game on TV," Figueroa says. "It was definitely involving Michael Jordan and the Bulls. And my mother turned the corner, and she started to watch the game with me. And she said, 'Oh, do you know my uncle Leo invented the shot clock?' I was, like, 'What? Really? You never told me that.'"

Figueroa knew that his mother had been raised in upstate New York, but this was the first time she had mentioned her Uncle Leo — who was, of course, Leo Ferris. From then on, whenever she would catch her son watching an NBA game on TV, she’d share another story of her uncle and his connections with the league.

"And, you know, I'd go to school, and I'd say, 'Hey, my great uncle invented the 24-second shot clock.' And they'd turn around, my friends, and say, 'Well, yeah, my grandmother invented the 3-point line,'" Figueroa says. "And they just wouldn't believe me. And so, I remember at an early age being frustrated by my lack of proof."

During the summers, Figueroa visited his mother’s family in upstate New York, and that’s where he met his Aunt Beverly, Leo’s wife.

She’d come to family reunions and bring an envelope filled with old photos and newspaper clippings. Figueroa hung on her every word.

It must have been a relief for Beverly Ferris to find such a receptive audience. Leo was growing weaker by the day. Along with her daughter, Jamie, Beverly provided all of Leo’s care at home. And she still hadn’t found anyone, other than journalist Sean Kirst, who believed her.

"She fought many years, even when he was still alive, even when her daughter was getting sick. She fought and fought to get the truth out," Figueroa says. "I can't even imagine how difficult that must have been for her."

Decades later, Christian Figueroa would pick up where his great-aunt left off.

From Upstart NBL President To NBA Co-Founder

Meanwhile, Sean Kirst was digging into the stories Beverly Ferris had told him — finding corroboration the best way he knew how:

"Sitting with a lever at a microfilm machine in the back of a library and reading clips," Kirst says. "And just going day by day and reading the things, because in the old days they reported everything."

Kirst says if not for Leo Ferris, the NBA as we know it might never have been formed.

"You can argue that if a meteor fell on Leo at that moment, he should be in basketball's Hall of Fame. I mean, because he's the guy who brings about the NBA, right? But he doesn't stop there. That's what's so cool."

Sean Kirst

Back in the 1940s, there were two rival pro basketball leagues. The larger, more established, Basketball Association of America (BAA) and the smaller upstart, the National Basketball League (NBL). Ferris was the co-founder and general manager of an NBL team, the Buffalo, later Tri-Cities, Bisons.

Ferris and the other NBL executives knew their league couldn’t survive if it had to compete with the BAA, so …

"So, they make him president of the NBL with the mission to be: force a merger with the BAA," Kirst says.

Leo Ferris did what upstart league presidents do. He outbid the BAA for the best players coming out of college. But then he came up with a crazy idea. Why settle for signing one college player at a time when he could sign a whole college team?

"Kentucky had a team that they called the Fabulous Five, and he creates a franchise for them," Kirst explains. "He says, 'If you guys come to our league, you can have the Indianapolis franchise. It'll be your team.'

"That is the move that broke the BAA's back. They say, 'OK, that's enough.'"

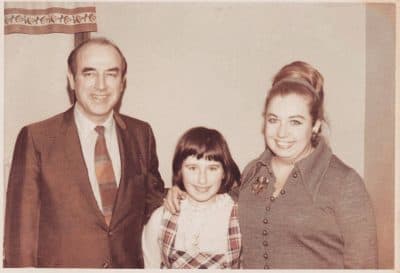

The old black-and-white photo Beverly Ferris showed Sean Kirst on that afternoon back in 1992 was taken on Aug. 3, 1949 — the day the two leagues merged to form the NBA. Five men stand smiling, their hands stacked on top of each other. Ferris is in the middle. His left hand rests on top of the pile.

"So you can argue that if a meteor fell on Leo at that moment, he should be in basketball's Hall of Fame," Kirst says. "I mean, because he's the guy who brings about the NBA, right? But he doesn't stop there. That's what's so cool."

Leo Did The Math

Sean Kirst had gotten at least one thing absolutely right in his story about Syracuse Nats owner/bowling alley operator Danny Biasone.

"Danny said something had to change," Kirst says. "You had to have a change in the time."

The idea of a shot clock was already out there. But how much time should be on it?

Leo Ferris did the math. By 1954, he was the general manager of Biasone’s team. Looking over box scores from games that had been hard-fought and exciting, he and Biasone counted an average of 120 shots, roughly 60 by each team.

It was Leo Ferris who took pen to napkin at the bowling alley bar. The game is 48 minutes long. Forty-eight minutes equals 2,880 seconds. Divide that by 120, and you’ve got the 24-second shot clock.

Leo Ferris, not Danny Biasone, presented the clock to the rules committee meeting. All of this is documented in old newspaper clippings.

"Just to give you the importance of this thing," Kirst explains, "Bill Himmelman, the NBA historian for many years once said, 'There are two moments of importance in basketball history. There's the moment when Dr. Naismith nails a peach basket to the wall. And there's the moment when they turn on the 24-second clock.'"

Leo’s role in all of this — the shot clock, the formation of the NBA and more — was thoroughly reported in the Post-Standard and other newspapers of the day. So why, when Beverly Ferris called the sports desk 40 years later, did no one believe her story?

Fight To Re-Write Family Legacy

"He did all this before he was even 39 years old," Figueroa says. "He left the game at 38 years old."

That was just months after the shot clock was introduced. Christian Figueroa says it would take decades before anyone realized the importance of the things Leo Ferris had done.

"By then he was sick, and by then he was decades out of the game, and by then history had been re-written, frankly," Figueroa says.

Leo Ferris died in 1993 after a 25-year battle with Huntington’s disease. Beverly Ferris died in 2010, without seeing her husband recognized for his achievements. Leo and Beverly’s daughter, Jamie, also inherited Huntington’s. Figueroa visited her before her death in 2014.

"Even as all her muscle functions were deteriorating, she still would talk about him," Figueroa says. "She would come alive when she got to talk about Leo. When she passed in 2014, it got me thinking about another family member passed, another family member who knew Leo, another family member that had fought for Leo."

Not every family would have fought so hard. Some might have felt that Leo’s post-NBA career in real estate was enough evidence of a life well-lived. But for Beverly and Jamie, recognition was everything.

By the time his cousin Jamie died, Christian Figueroa had a son of his own. A son who loved basketball.

And Figueroa decided it was his turn to pick up the fight to set straight his family’s legacy.

"So this is for Leo, for Aunt Beverly, this is for cousin Jamie, and for all the people who suffer and have suffered from Huntington's disease," he says.

And Christian Figueroa’s efforts have paid off. For the past two years, Leo Ferris has been nominated for the Naismith Hall of Fame.

It’s a start. But just last weekend, the Hall announced its 2017 inductees. Once again, Leo Ferris was not on the list.

But Sean Kirst believes it’s just a matter of time.

"How could any fair person, hearing our conversation here today, how could you say, you know, that he doesn't belong in there?" Kirst asks. "That this thing is happening, that a great nephew in Boston embraces the cause of this forgotten upstate basketball pioneer, it's just a joyous story. And I hope it has a joyous culmination."

"Me too," I say.

How could I not?

This segment aired on April 8, 2017.