Advertisement

Warriors' Journey From Mean To Nice, Bad To Good

Resume

Want more Only A Game? Follow along on Facebook and Twitter.

This is the story of one of the most controversial moments in NBA history. It sparked a national discussion on race and violence and revealed fears and prejudice lying just beneath the surface of the sports world. But without this incident, the Warriors might not be the team they are today.

Trying To Create A Winning Culture

When David Steele was assigned to cover the NBA for the San Francisco Chronicle in 1996, the Warriors were coming off two losing seasons in a row — and desperately trying to become a winning team again. The front office thought coach Rick Adelman was part of the problem. They believed he was too soft on players and let them get away with bad behavior on and off the court.

"When they, all of a sudden, turned up one day and said, you know, 'P.J. Carlesimo is the new coach,' we were just kind of like, 'What is — what?'" Steele remembers.

P.J. Carlesimo was a star college coach. He was young, energetic and aggressive. But some of his former players said he constantly yelled and cursed — that he was borderline verbally abusive.

It was a coaching style that worked with younger, college players, but there were doubts that it would translate well in the pros.

"But he somehow had convinced them that he was the guy who was going to whip them into shape," Steele says.

The Warriors were banking on their new coach — and a new attitude. And they built a marketing campaign around that.

"It was called 'No More Mr. Nice Guy,'" Steele says. "There were billboards. There was a song that went along with it, that started out with the players, singing 'Kumbaya,' and then it would be the whole record scratch thing, and then, 'No more Mr. Nice Guy! No More Mr. Clean!'"

Carlesimo was all in on "No More Mr. Nice Guy." He appeared on billboards wearing dark shades and a leather jacket, his arms crossed, glaring into the camera.

"The fans were eating it up," Steele says. "'Cause the fans wanted to see a winner again."

Twenty-year-old top draft pick Adonal Foyle was also getting ready to join the team that season.

"This is gonna be cool, this is amazing," Foyle recalls. "And I can’t wait for what the ride is going to bring."

The funny thing about Foyle, originally from the Caribbean — he may as well be named "Mr. Nice Guy."

Foyle says Carlesimo’s style was rough, but that he was also nice, funny, good with the media. He just wanted things done the right way. His way.

So, new coach, new attitude. But on the court, the team was still built around a holdover from the old franchise: All-Star shooting guard Latrell Sprewell, or "Spree."

'He Was So Talented ... He Was Kind Of Volatile'

Three things to know about Sprewell.

No. 1:

"That he was exceptional," Foyle says. "I mean, he was so talented. He can shoot, he can slash, he can rebound."

"Sprewell was just electrifying," Steele continues. "He was explosive, he never backed down. He was just a lot of fun to watch."

No. 2:

"He was kind of volatile," Steele says.

Writers and teammates say Spree could be reserved, emotional and hard-edged. A few times he was near the center of drama off the court. He got into a few fights with teammates. There was a rumor one got particularly vicious:

"And Sprewell going after him with a two-by-four," Steele recalls.

No. 3:

Sprewell was cast as a team leader, but didn’t necessarily want that role. Foyle says he would show up, work hard, then leave.

There was tension between Sprewell and Carlesimo from the beginning.

"By the time the regular season started, Sprewell stopped talking on the record," Steele says. "It was a sign that everyone should have, sort of, picked up on."

The Warriors lost their first game, then their second and their third ... then, nine straight. They weren’t just losing; they were getting crushed.

"It was depressing," Foyle says with a laugh. "I mean, from a player’s perspective, losing is just terrible."

"I was extremely surprised that it was as bad as it was. Really kind of blew me away, and I said, 'Wow, he really did snap.'"

David Steele

Losing was definitely getting to Carlesimo. He doubled down on his aggressive style.

"'Get back, get back,' you know," Steele says. "'Push, push, pass, pass! Back cut, back cut!' Just non-stop noise from the coach."

Spree wasn’t talking to the media, but he talked with Steele off the record.

"It was all P.J. He was just really getting on his nerves," Steele says. "He was just trying to shut him out, trying to tune him out — didn't know how much longer he could take it. He didn't want to do anything like demand a trade or cause a scene."

'He Really Did Snap'

Dec. 1, 1997: The Warriors — coming off a five-game losing streak — held a practice at their facility in downtown Oakland, on the fifth floor of the Marriott.

The session had been closed to the media, but Steele and a few other reporters were allowed in for the last few minutes for what they thought would be a normal round of interviews.

"We walked in, and players were shooting free throws. And it was pretty easy to notice that Sprewell was already gone," Steele says. "And P.J. walks over, and he's got a, you know, polo shirt on just like what he'd been coaching in, and he's got these great big red marks around his neck."

Steele knew something serious had happened, but no one was talking. Even today, Adonal Foyle doesn’t get into the details:

"The practice started like any other," he says. "Nothing unusual, and so I was in the middle of doing a post move when the incident happened."

Based on testimony from Sprewell, Carlesimo and 20 other Warriors players and staff, here’s what happened:

Sprewell was doing a routine passing drill when Carlesimo told him to make better, or crisper, passes. Sprewell said he was. Carlesimo called his name again. Sprewell yelled at his coach and Carlesimo told him to leave the practice. And that’s when Sprewell lost it and put his hands around Carlesimo's neck.

Carlesimo said the entire incident lasted around 10 seconds and that he was having trouble breathing. Both testified that Sprewell said, "I’m going to kill you."

Teammates and coaches separated them. Sprewell went to the locker room while Carlesimo somehow resumed practice. Fifteen to 20 minutes later, Sprewell rushed his coach again, swinging wildly and punching him in the chest and jaw. Again, they were separated.

A league security rep escorted Carlesimo home. Oakland police were called to the gym to guard it in case Sprewell returned. He never did — though Carlesimo had a security detail outside his home for a week.

Steele had only heard bits and pieces of this story by the time he was called back to the Warriors' practice facility for a press conference at 9:00 p.m.

"I was extremely surprised that it was as bad as it was. Really kind of blew me away, and I said, 'Wow, he really did snap.' That became a national story, like, immediately."

"We probably went from three beat writers to thousands of reporters, you know, the day after," Foyle says.

'Everybody Had An Opinion About It'

"It took on so many dimensions, and it took them on like instantaneously," Steele says. "Everybody had an opinion about it."

Articles noted Sprewell’s imposing stature, his hair, braided in cornrows. He was called a "thug" and a "gangster."

Neil Rogers, a former Florida radio host now inducted in the National Radio Hall of Fame, responded to a caller who suggested that NBA players were under "tremendous pressure" by saying:

Oh, get out of here. Call one of those sports wimp shows, OK? 'They play under tremendous pressure.' You jackass. Scumbag is a scumbag, pal. You can take the boy out of the city, or out of the ghetto, but you can’t take the scum out of the bag.

San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown made headlines of his own when he said that coaches shouldn’t be yelling at grown players like they were kids, and maybe Carlesimo deserved to be choked.

Carlesimo didn’t want to press criminal charges, but league commissioner David Stern was grappling with how Sprewell should be punished. There was pressure to make an example, because the NBA had an image problem.

According to Steele, basketball was seen as "the sport that is harboring criminals and thugs and people who don't obey the rules and people who are out of control."

Stern didn’t grapple for long. Just two days after the incident, the NBA gave Sprewell the harshest penalty in league history for a non-drug related offense: a year-long suspension without pay. Several other players in the league spoke out, claiming the penalty was unreasonable. Some even threatened to boycott games.

"There was this universal idea that, yeah, he stepped over the line. But a lot of people recognized an extreme reaction to it that seemed out of place," Steele says.

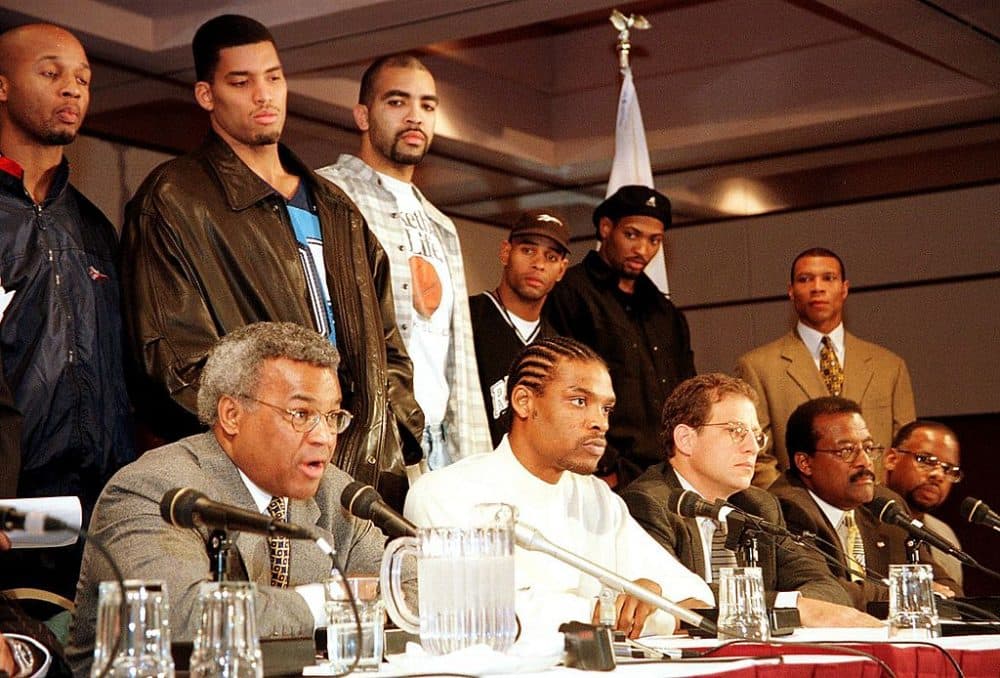

A week after the incident, Sprewell held his own press conference. He apologized and admitted his actions crossed the line. But it was also a show of strength. Spree was flanked by a nine-member legal team, including Johnnie Cochran, just two years after he had defended O.J.

"That, sort of, sent a signal to everybody that's, like, 'Oh, we're just not going to quietly and humbly accept whatever it is you're gonna punish him with, just for the good of the league,'" Steele says.

The National Basketball Players Association appealed the suspension on Sprewell’s behalf. The hearings dragged on for months.

Eventually, an arbitrator deemed the initial suspension too harsh. Sprewell was barred from the remainder of the season, but was allowed to return to the league the next year. In his ruling, the arbitrator suggested that one day, Sprewell might even serve as a role model.

Sprewell's Return — And The New Warriors

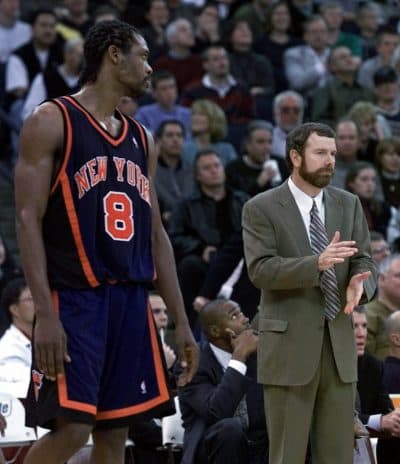

Sprewell came back and led the New York Knicks to the NBA Finals that next year, but the role model thing never really panned out. He recently appeared in a Priceline commercial making fun of his own reputation as a headcase.

Sports Illustrated’s Chris Ballard says in the years following the incident, the Warriors’ front office deliberately tried to bring in "high character" players.

"There was this feeling of, 'OK, if we’re not going to be good, let’s at least be likable,'" Ballard says.

The Warriors signed veteran players without much upside.

"And these were all guys you’d want to have dinner with," Ballard continues.

But that didn’t equal wins. The Warriors didn’t make the playoffs for another 10 years.

Ballard says the nice guy thing only works when the talent is there, too. And in 2009, the Warriors found a player with that combination when they drafted Stephen Curry.

"Because if your best player plays with joy and your best player is not putting himself above the team, it's a lot easier to get all of the other players to do that," Ballard says.

These days, the Warriors are known for their top talent and team chemistry. They’re even able to absorb more volatile personalities because they’re led by a coach who relates to and shows respect for his players. All of these attributes were learned the hard way, taught by Sprewell and Carlesimo, and a decade of losing following one of the lowest points in NBA history.

As Adonal Foyle puts it:

"The Warriors team of today had to go through the wilderness of desperation to come to find its true soul and its true purpose."

This segment aired on June 3, 2017.