Advertisement

Four Futile Years As A Yale Oarsman

Resume

When Mike Danziger began his freshman year at Yale in 1981, he received a letter from the lightweight crew coach. The coach informed Danziger, who is 6-foot-4 and then weighed about 145 pounds, that he had the perfect body for the lightweights.

Danziger had never been told he was perfect for anything. He showed up at the boathouse. And there he remained.

"I rowed all four years at Yale," Danziger says.

"And how did your coaches feel about that?" I ask.

"My coaches were a bit frustrated with me," Danziger says. "Because they wanted to get rid of me."

But they couldn’t cut him. Tradition at Yale has it that crew doesn’t cut anybody. As long as you showed up, you could compete for a seat in a boat. The only way to get cut was to quit.

But as long-time Yale coach Dave Vogel might have put it, though Mike Danziger was persistent, he wasn’t any good. So he rowed in the boats – called shells – full of other guys who weren’t any good. And like the other guys in his boat, he understood absolutely the distinction between the accomplished oarsmen and everybody else.

"I literally worshiped some of the guys in the top boat," Danziger says. "We described them as 'gods.' There’s Mike Hart. He’s a god. Andy Morley. He’s a god. I wouldn’t dare speak to them. And it took me two years to gather the courage to introduce myself to Mike Hart."

Rowing may be the most demanding of sports. The practices are grueling when the oarsmen are on the river, and worse during the winter, when they’re inside in tanks or on rowing machines called ergometers, or "ergs." The repetition can be numbing. Like wrestlers, rowers on a lightweight crew often have to cut weight, which means hunger and thirst and time in the sauna.

And oarsmen like Mike Danziger, if there are any other oarsmen like Mike Danziger, begin to understand fairly early on that they aren’t likely to become "gods".

So why do they keep coming to the boathouse? In part, at least, it’s to pursue something they call "swing." Danziger first heard about it when he was riding back to the campus after a practice on the river. He was sitting beside one of the members of the women’s crew.

"And she said, 'How was practice today?'" Danziger remembers. "And I said, 'Oh, it was brutal.' She said, 'Did you guys swing?' And I said, 'What’s 'swing'?' She said, 'It’s like an orgasm. I mean, you can’t really describe it. But you know when you’re having it.'"

The conversation gave Danziger something to which he could aspire.

"Swinging is elusive," Danziger says. "And it’s that moment where every single oar goes into the water at the exact same moment. And, not only that, the power is applied at exactly the same time throughout the stroke, and the oars come out the same. And at that moment, when you swing, the sum is really greater than the parts. And the boat seems to be flying on the water."

"It happened to me once, and I’ll never forget it. And it validated everything that I did, and it was incredible."

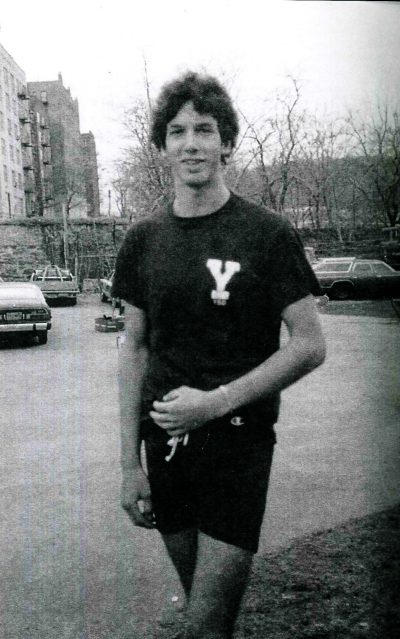

Mike Danziger

"Our boat was getting ready for the Harvard-Yale-Princeton race, which was the biggest race of the year for us," Danziger says. "All of a sudden, these eight misfits with their misfit coxswain started to float on the water. And we could feel it. And it was amazing. And all of a sudden, we were ahead of the third varsity boat. They weren’t swinging. The coach’s launch came over next to us, and Dave Vogel said, 'You guys did it. And if you can do that next Saturday, you’re gonna cream Harvard and Princeton.'

"Well, we didn’t, and we got blown away. But for that one moment, I knew what it was like to swing.

"It happened to me once, and I’ll never forget it. And it validated everything that I did, and it was incredible. And there are guys who – every single day – they have that experience. And what I wonder is, 'Does that make it less special? Do they take it for granted?'"

Given that Danziger wasn’t making much progress toward godhead while he was at Yale, he welcomed the opportunity to row elsewhere. In Italy, as it turned out. Though he’d gone there during the summer between his sophomore and junior year not to row, but to study art and architecture.

"And I was walking through Florence, and I was looking at the Ponte Vecchio, this old bridge that passes over the Arno," Danziger says. "And as I looked down, I saw boats coming out of a boathouse. And it was the Società Canottieri Firenze, which is the society of rowers in Florence. And I walked in there, and it was really a social club. People were drinking their cappuccinos.

"And this very large, incredibly well-built guy came up to me. And he said, 'Ciao. Mi chiamo Roberto.' So I said, 'Ciao. Mi chiamo Michele.' And then he asked me if I wanted to row with him."

Roberto didn’t mention his credentials, but later the steward in the boathouse told Danziger that Roberto was no weekend sportsman.

"Roberto was an Olympic rower from the Italian National Team," Danziger says. "Mike Hart and Andy Morley would do anything not to row with me. And here was a guy who said, 'Let’s take out a boat together.'"

In Italy, oarsmen didn’t have to be divided into "gods" and "scrubs," and never the twain shall sit in a boat together. Danziger rowed with Roberto twice a week that summer, which had to raise his stock, right?

"When I went back to Yale in the fall for rowing, I thought, 'Well, I spent the whole summer rowing with an Olympian, and this will be great,'" Danziger says. "And Dave Vogel read the call of all the people that he was expecting, and my name wasn’t on his list. Because he just figured that I had quit. And not only hadn’t I quit, but I spent the whole summer rowing with an Olympian. Who else had done that? And I remember he said, 'Oh, Danziger. You’re back.' And I said, 'Yup. I’m still here.' And I remember what he said. He just said, 'Well, suit yourself.'"

So Danziger did that. When he wasn’t rowing, he suited himself, though not precisely as the coach might have imagined:

"I was the Yale bulldog," Danziger says. "And the Yale bulldog wears this blue, furry suit. He’s got a papier-mâché hat on, and gloves, and the outfit came with a letter sweater."

Lettering as a rower didn’t seem likely. But being the mascot sounds like fun, eh? Sometimes, but not always, as Danziger discovered – on the job – at a Yale football game, where the actual Handsome Dan, an authentic bulldog, was being introduced to the crowd.

"And we hated each other," Danziger says. "We came out to the 50 yard line, and he slipped his leash. And he took off after me, and I started running away. And these were the days when there were 40, 50 thousand people at the Yale Bowl. And I got to the sidelines, and I thought, 'Ah, I’m safe!' But I wasn’t safe. Because these dogs are tenacious. They’re bulldogs.

"And I turned around, and he was right there And he pounced on top of me and started mauling me. And I could hear the crowd cheering. And he’s ripping away at my skin. And finally, the security guards came and pulled him off. And I figured, sort of, after that humiliation, that sweater was mine. So I did end up with a letter, but it was because I was the mascot. Not because I achieved anything."

As previously revealed, Mike Danziger rowed throughout his years at Yale. He never got anywhere much, but he never quit. And he doesn’t regret the choice he made, though it came with consequences.

"You know, I had an opportunity when I was at Yale to spend time every single day with the very smartest people in the world, talking about the things that turned them on the most," Danziger says. "And sharing their passion and their knowledge and their experience and their perspective with me. And I didn’t. But I got stuff out of Yale that maybe nobody else did. Or very few did. Which was cold comfort to my dad, who described paying the tuition at Yale like buying a brand new car every year and driving it off a cliff."

After Yale, Mike Danziger began the Steppingstone Foundation. Over the years, it has helped a great many disadvantaged children get a college education. Somewhere along the line, Mike Hart, one of Danziger’s gods, became godfather to one of Danziger’s sons. More about Michael Danziger’s experience as Yale’s worst oarsman ever is available in his new book, "Small Puddles."

This segment aired on July 15, 2017.