Advertisement

History Of The Forward Pass

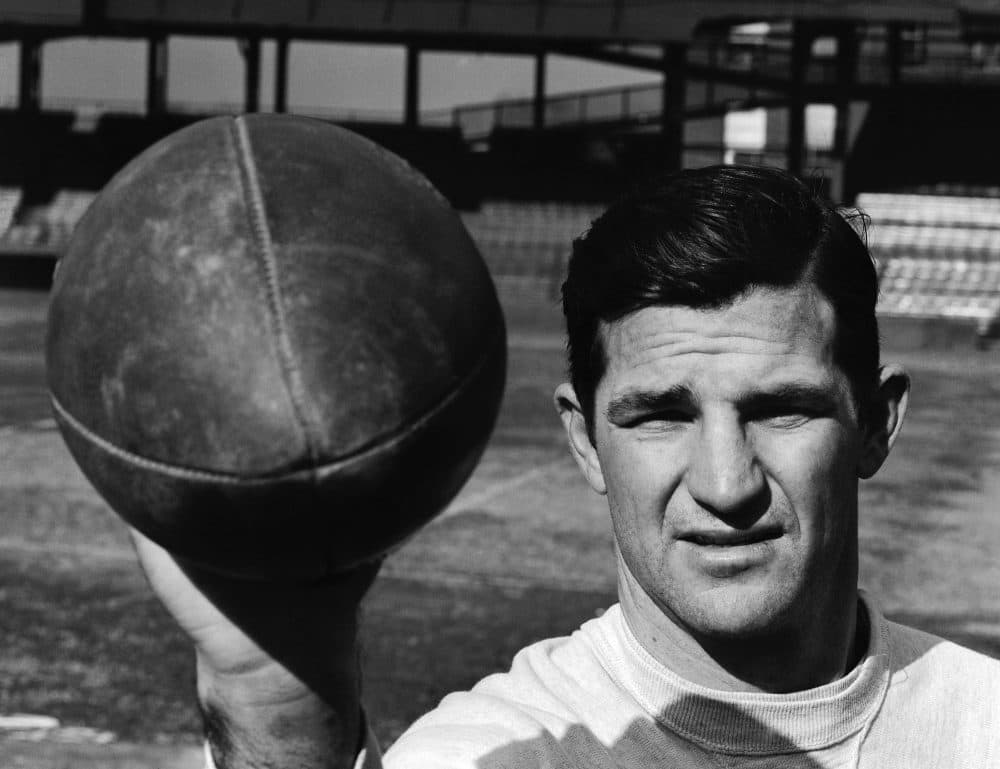

Searching For Slingin' Sammy Baugh

Resume

This is Part 4 in our episode on the origin of the forward pass.

For more, see: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Twenty-two years ago, sports writer Dan Daly flew to Dallas and started driving west on Highway 20 toward a part of Texas called the Big Empty.

He was searching for 81-year-old Sammy Baugh.

It had been decades since Baugh retired from the NFL as the all-time leader in passing yards and touchdowns — and he hadn't been seen outside of Texas in years.

"I've got my directions scribbled down on a sheet of paper," Daly recalls. "And I'm praying to god they're right. Because some of them sound really, really bizarre, like, 'Take a left at State Route 580,' and I'm thinking, 'What if there's no sign? What if I just drive forever and end up in Nebraska or something?' "

Eventually, Daly turned down a dirt driveway. All around him, it was flat as far as the eye could see. The driveway led to a little white house.

"I was surprised how small a place it was," Daly says. "I knocked on the door. No one came to the door. So I go around to the other side of the house to see if there's a window I could look in to see if there's anybody there. And I see this glow behind the drapes. It's clear that somebody's watching television. So I knock on the window, and the drapes spread, and there's this big guy."

It was Sammy Baugh. He came to the door.

And for the next five hours, the two men talked.

Until Daly shared his mini cassettes with me last week, no one else had ever heard the recording of their 1995 conversation.

For most of the five hours, Baugh laughs and tells stories about his time in the NFL — occasionally pausing to comment on the college football game on the TV, and more than occasionally pausing to spit.

"He had this gigantic plastic cup with a handle on it — the kind that you get if you're buying, like, a Double Gulp," Daly recalls. "And he used it as a spittoon because he was a tobacco chewer. And every minute or so he'd lean over and grab the handle and spit into the cup."

And then there was Baugh's language — profane, but not unfriendly.

"He didn't have that social filter that many of us have," Daly says. "It tells you that he probably wasn't used to being interviewed all that much. That was part of what was going through my mind — just how isolated he was."

Sammy Baugh — the greatest quarterback of his generation; the guy who helped make the NFL the forward pass-obsessed league that it is today — had become a reclusive cowboy.

From Third Baseman To NFL Prospect

Baugh grew up in a small Texas town. He was far more interested in playing sports than riding horses. He didn’t have anything to do with ranching.

Baugh was a decent high school football player, but his No. 1 sport was baseball. He played third base and had a great arm.

In 1933, Baugh joined the baseball and football teams at Texas Christian University. He expected to play third base and punt for the football team. He’d always been good at that.

Most college teams from the East and Midwest were still avoiding the forward pass, but Dutch Meyer – the football and baseball coach at TCU – loved it.

"Hell, we could throw the ball any time we wanted to," Baugh told Daly. "And Dutch told us, 'If you've got a reason for doing it, I'll never second guess you.' "

Soon Meyer figured out that his third baseman with the strong arm would actually make a darn good passer.

"Sammy was a sensation. No one had ever seen anybody throw the ball as accurate as he threw it."

Dan Daly

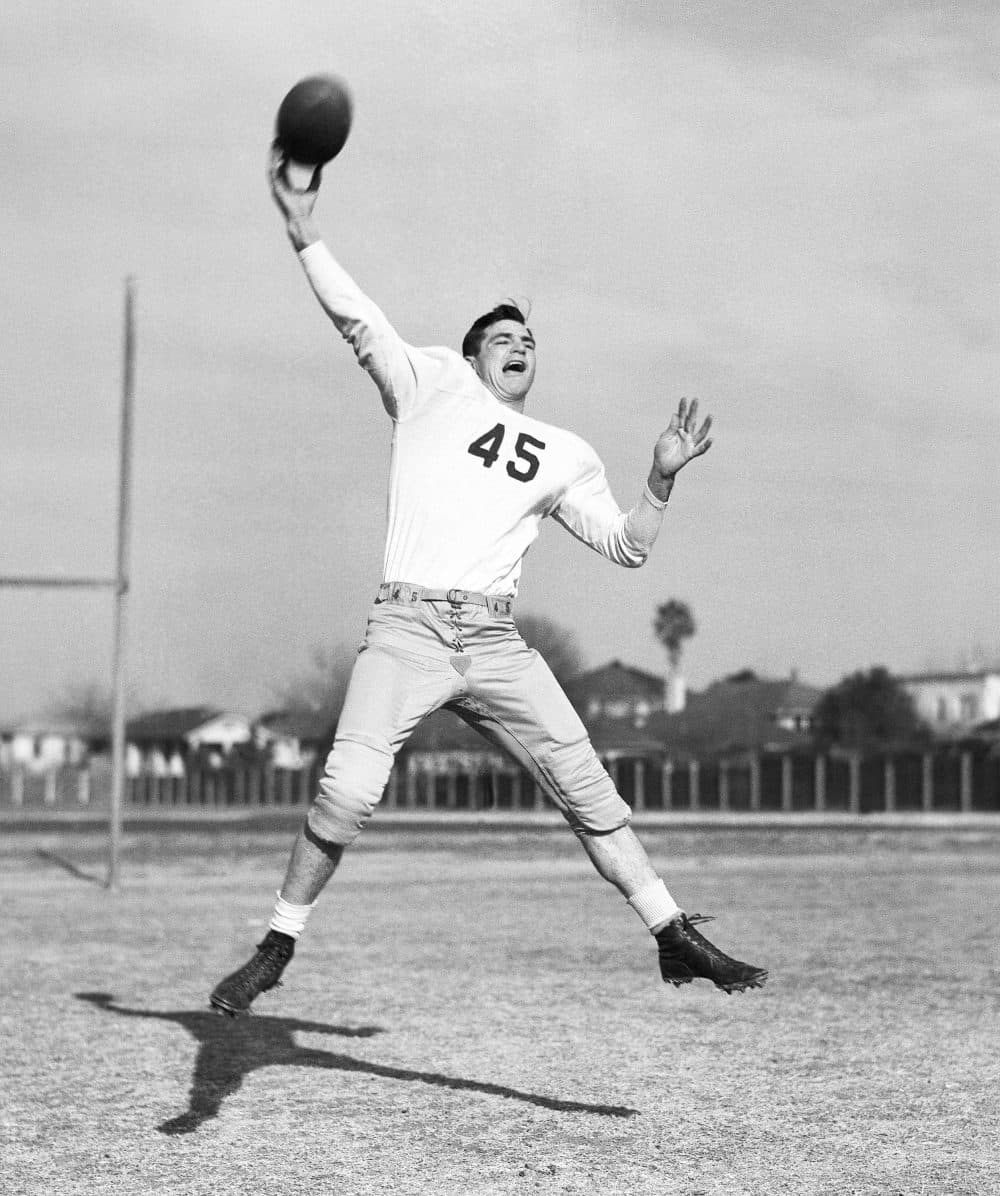

During his junior and senior seasons, Baugh led the country in both punting and passing.

And that caught the attention of the owner of the NFL franchise in Washington D.C.

Creating A Cowboy Image

George Preston Marshall had a plan for the skinny kid from Texas who the fans and writers were already calling Slingin' Sammy.

Washington drafted Baugh No. 6 overall. And before Baugh boarded the plane for D.C., Marshall instructed him to wear a cowboy hat and boots.

"Marshall was such a showman and he wanted to create this image of the Texan and the cowboy in the minds of the Washington market," Daly explains.

Baugh wasn’t used to wearing cowboy boots. He said they hurt his feet.

But he recovered in time to play Game 1.

"Sammy was a sensation," Daly says. "No one had ever seen anybody throw the ball as accurate as he threw it."

That year Baugh led the NFL with 1,127 passing yards and eight touchdowns. Washington won the championship.

Soon Baugh was being asked to fly off to Hollywood.

In 1941, Baugh starred in a serial Western called "King of the Texas Rangers." (It's your basic Cowboys vs. Nazis story. Nazis try to sabotage the oil fields; cowboys try to stop them.)

Baugh kept a low profile in LA. According to Joe Holley’s biography “Slingin’ Sam,” Baugh ate lunch on set with the technicians. They had the best stories.

At night he stayed in. Baugh told a magazine writer, "It didn't make sense to be showboating all over Hollywood and spending a lot of money for a steak when I could take that money back to Texas and buy a whole cow."

And that’s what he did. In fact, he bought an entire ranch 250 miles west of Dallas. He was starting to become a real cowboy.

'We Don't Give A F--- What You Do On Weekends'

Once World War II began, Baugh’s ranch provided beef for the war effort. That meant he wasn't drafted. He kept playing – and during the 1943 season, against lower-grade competition, he led the NFL in passing, punting and interceptions. (Baugh played safety, too.)

In '44, the draft board told Baugh he had to work at his ranch full time. That was OK with him – he liked the ranch. But he asked the draft board if he could still fly to games on weekends.

Baugh says the draft board told him, "'We don't give a f--- what you do on weekends. If you wanna go somewhere on weekends, go.' I said, 'Well, I'll be back Monday morning.' They said, 'Hell, we don't care. You can get back Monday afternoon.' "

Sammy Baugh retired in 1952 after 16 seasons in Washington.

Joe Holley wrote of Baugh, “What Babe Ruth’s home runs did for Major League Baseball during the 1920s, Sam Baugh’s passing did for the National Football League a decade or so later.”

After retiring, Baugh coached for about a decade. But a funny thing happened: the guy who’d once complained about the cowboy boots hurting his feet realized he liked ranching better than football.

He started spending all his time raising cattle and roping.

In 1963, he was one of two unanimous selections for the Pro Football Hall of Fame's inaugural class. He’d often get asked to attend events at the Hall of Fame or in Washington, but he'd decline.

Baugh told Dan Daly he hated wearing suits.

"It just irks the hell out of me to have go anywhere where I have to put a tie and suit on," Baugh said.

And after all those trips from Texas to D.C. he especially hated flying.

So if anyone wanted to see Sammy Baugh, the quarterback who'd changed football, they'd have to go to him.

And that's why Dan Daly set out on that journey to the Big Empty 22 years ago to hear Sammy Baugh tell stories.

Eventually, Daly realized it was time to go — not just because five hours had passed, but because Baugh had filled his plastic cup with tobacco spit.

So Daly started the 250 mile drive back to Dallas.

In 2008, Sammy Baugh died at the age of 94.

'A Pretty Good Cowman'

Baugh's ranch is still in operation.

His son David is in charge now. I called him up the other day.

"Could you describe what it looks like out your window right now?" I asked.

"Well, the wind's blowing, and it's about 35 degrees. It's kinda cold," David Baugh told me. "We've been feeding cattle, and the sun is shining brightly. And it's a pretty morning."

David said his father didn't talk much about his role in developing the forward pass. He was prouder of his ranch.

"Oh, he was a real cowboy," David said. "On his tombstone, it says, 'A pretty good cowman,' and that's how he wanted to be remembered."

This segment aired on December 16, 2017.