Advertisement

Forty Years Later, Disagreement About Disco Demolition Night

Resume

On July 12, 1979, 48,000 fans packed Chicago’s Comiskey Park for Disco Demolition Night. Some spectators went out of control.

"They got really, I would say, violent," says Darlene Jackson, who was 10 years old when the White Sox held Disco Demolition Night. "It was so primal and tribal."

Jackson was jolted as she watched the postgame news reports.

"I remember sitting in our living room — we had green carpeting — and sitting on the floor," Jackson says. "And my dad in the background saying, ‘These people have lost their minds.’ "

In recent years, some have said Disco Demolition Night had a dark side, a side many didn’t see — or didn’t want to see - 40 years ago.

Veeck's Big Idea

In the late ’70s, the Chicago White Sox were owned by Bill Veeck. Veeck was famous for his creative promotions, including a pyrotechnic scoreboard and a shower near Comiskey’s center field bleachers. But in 1979, neither fireworks nor personal hygiene drew hordes of fans.

"We were not doing well," says Bill's son, Mike Veeck .

In 1979, Mike Veeck was the White Sox’s assistant business manager and promotion director. At the season midpoint, the White Sox were 35–45. The team was drawing fewer than 10,000 fans per game. The poor attendance called for more creatively extreme measures.

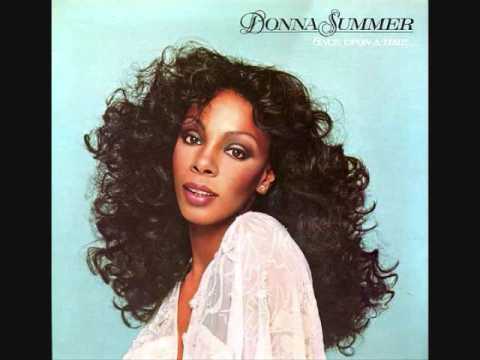

While the Sox struggled, disco was at the peak of its popularity. It was everywhere — in movies, nightclubs, clothing shops and on the radio. The genre had grown far beyond its more obscure beginnings in the mid-’70s as a dance club phenomenon especially popular with African Americans, Latinos and the gay community. But in 1979, there was a growing backlash against disco, particularly at one Chicago radio station.

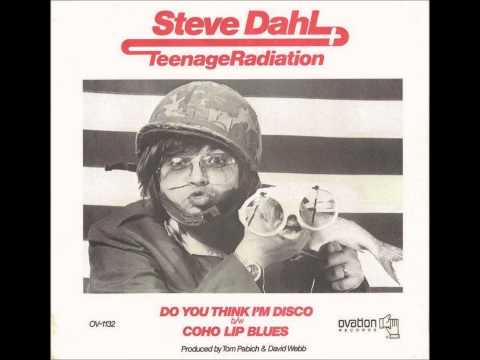

"I caught wind of a guy named Steve Dahl blowing up disco records," Mike Veeck says.

Steve Dahl had lost his job spinning rock records when the radio station he worked for changed to an all-disco format. He quickly found another job at another rock station. But he was still angry.

"And every morning, I would play a disco record," Dahl says. "I’d run the needle across the record. And then I would have an explosion — like, blowing up the record."

(Just to be clear, Dahl’s talking about explosion sound effects. The real explosions would come later.)

Dahl started holding "Death to Disco" rallies at nightclubs. He even hit the airwaves with his own 45 single, a parody of Rod Stewart’s disco mega-hit "Da Ya Think I’m Sexy?"

"Rod Stewart, The Stones, a lot of mainstream rock 'n' roll acts were putting out disco records," Dahl says. "I think that there was a feeling of disenfranchisement by the kids wearing the blue jeans and the rock 'n' roll T-shirts."

Dahl’s appeal to his growing fan base was too much for Veeck to resist.

"Steve was doing his 6:00 to 10:00 [a.m.] shift, and at 10:05, I'm standing at the door of the studio going, ‘Let me in. I got an idea,’ " Veeck says, knocking on the table.

Veeck presented his idea for a Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park. It would take place between games of a twi-night doubleheader against the Tigers on July 12. Admission would be just 98 cents for customers who brought in a disco record. Dahl agreed to give it a spin. Veeck had no idea what the promotion would turn into.

The First Game

Early on the morning of July 12, Mike Veeck met with a group of off-duty Chicago police who would be working security.

"And I told them in the morning meeting what we thought the estimated attendance would be," Veeck says. "I told 'em we were gonna have 35,000 people. They thought that was hilarious."

But by 4 o'clock that afternoon, about that many had lined up outside Comiskey.

Andrew Brown was one of them. He was there on an outing with his Cub Scout den.

"I was 10 and a massive baseball fan," Andrew says. "This is my first double header. This was a big deal."

Andrew and his fellow Cub Scouts entered Comiskey Park. He says he paid little mind to banners hanging from the upper deck that read “Disco sucks!” He was too excited about the baseball and the hot dogs he’d soon be eating in the outfield picnic area. It was a 10-year-old’s dream.

But when he made his way to his seat along the first base side, Andrew noticed that something was very different.

"The place was really crowded," Andrew says. "I mean, really crowded. There were no empty seats."

"And clearly a lot of people who were not there for the baseball," says David Brown, Andrew’s older brother. He was there, too. "A lot of young guys in concert T-shirts."

"... when Steve rode in on his Jeep, the electricity picked up several volts."

Mike Veeck

"When the game actually started, I was working the seats," says Dave Gaborek, who was a teenager selling soda pop that night. As the first game began, he noticed that not all of the paying customers had left their disco records in boxes at the gates, as they were supposed to do.

"They were just throwing records periodically on the field," Gaborek says. "Kids were whipping them out of the upper deck. So it was starting to become a little mayhem-ish."

But Dave Gaborek and everyone else in attendance hadn’t seen anything yet. In the bottom of the ninth of the first game, chants of "disco sucks" almost drowned out the sounds of baseball.

The White Sox lost the first game. And as the teams prepared for the second, DJ Steve Dahl took the field in a military Jeep. He wore a helmet and army fatigues.

"And when Steve rode in on his Jeep, the electricity picked up several volts," Veeck says. "We went from 120 immediately to 220."

The Jeep stopped in center field. Dahl grabbed a microphone and whipped the crowd of about 48,000 into a frenzy.

"Since I didn't think anybody was going to be there, I had no prepared remarks," Dahl says. "So I just yelled stuff."

The Veeck’s motto had always been "Fun is good." But Dahl’s tone was not fun. He led a chant of "Disco sucks."

"And we’re never gonna let ‘em forget it!" he shouted. "They’re not gonna shove it down our throats! We rock 'n' rollers will resist, and we will triumph!"

From there, Dahl directed attention to a large box in center field. It was full of some of the disco records that had been collected at the gates. Then someone lit a fuse.

There was a huge explosion.

"And records went everywhere, and parts of the box caught on fire," Dahl says.

"It was a hot night, and the wind wasn't really blowing," Andrew Brown says. "And so, this almost smog or smoke just settled on the field and gave it, sort of, this surreal aspect to it."

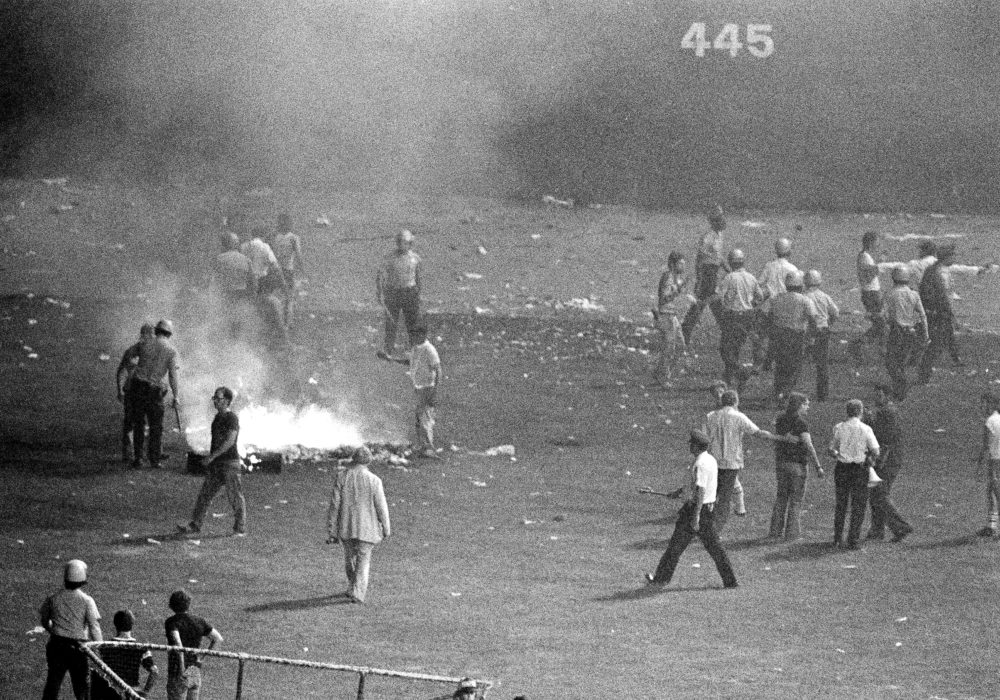

When the smoke cleared a bit, the damage became evident.

"I do remember it taking out a good portion of center field," David Brown says. "I mean, there was a huge crater after this was done."

'Hell Broke Loose'

Dahl hopped into the Jeep.

"We kind of went around the stadium once on the warning track, and people were throwing cherry bombs and beer at us," Dahl says. "And those were the people that liked us. Went out through the centerfield gate."

"And at that point, hell broke loose — people were on the field racing around, disco records flying," David Brown says.

"I remember looking over to my right and seeing a guy slide down the foul pole from the upper deck," Andrew Brown says. "And that's where I was kind of like, ‘Whoa.’ "

"People jumping from the center field bleachers," Mike Veeck says. "[It] was a 40-foot drop at old Comiskey. It was safe to say that I had probably mistaken what was going to happen next."

As Dahl made his way back to the press box, he had no idea what was going on. But Dave Gaborek saw the whole thing.

"This kid — maybe 19 or 20, real long hair down his back — he ran across the outfield, and he slid into second base," Gaborek says. "And he picked up the bag, and he started waving it around. And then that caused an avalanche of all the kids just running on the field and burning banners."

An estimated 7,000 people took the field.

"Yeah, I think Mike Veeck will tell you that they were underestimated in terms of security," says, Dave Hoekstra, another of Chicago’s many Daves. He's the author of "Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died."

He watched as team officials took the field. One of them was Sox owner Bill Veeck, who used a wooden leg as the result of a war injury.

"And poor Bill Veeck’s walking around the field trying to get all these kids to calm down," Hoekstra says. "He’s walking around in his peg leg, and his peg leg gets stuck in a piece of sod, you know? And he can't move his peg leg out of the sod. But they just couldn't control the crowd. It got too many people on the field to control."

Some pulled up turf in centerfield and fanned the flames that were already consuming small piles of disco vinyl. With the chaos raging all around them, the umpiring crew and team officials discussed whether the field had been rendered unplayable.

"I distinctly remember Sparky Anderson, who was the manager of the Tigers, coming out to talk to the umpires," David Brown says. "I could read his lips — basically saying, ‘How in the heck are we going to get the second game underway ... or even played?’ "

"Then they got the riot police out there and then the mounted police came in on horses," Gaborek says.

"The Chicago police rolled in, and nobody’s gonna stand in their way," Andrew Brown says. "So they got the field cleared."

But the White Sox had to forfeit the second game. It was just the fourth forfeiture in modern MLB history.

Questioning Disco Demolition Night

Bill Veeck sold the team in 1981, and Mike was out of baseball for 10 years. He says Disco Demolition Night played a part in that.

But that’s not where the story ends. Because more people are now questioning the ideological underpinnings of Disco Demolition Night. Mike Veeck calls this "revisionist history."

"That angers me," Veeck says. "It had simply to do with choosing between rock 'n' roll and disco and dance clubs."

"It was a little bit deeper than, ‘We're just having a good time,’ " Darlene Jackson says.

Today, she's also known as "DJ Lady D." She's a well-known house music DJ in Chicago. She was 10 years old on Disco Demolition Night. Her favorite music then was disco. And when she saw the news reports featuring images of Steve Dahl in a military outfit, "Disco sucks!" banners, white rioters and smoldering piles of vinyl, she heard a message.

"I think part of what Steve tapped into was a little bit of this unspoken transcript, that, ‘This is the music of black people, of gay people, of Latino people — and we should not accept it. We should not try to be a part of it,’ " Jackson says. "And so that's why people perceive it as a homophobic and a racist event. The unspoken transcript, a lot of us heard it."

"I understand now that there was an underground gay disco scene and all, but we were unaware of all of that," Dahl says.

"You know, we were unaware of the origins of it. We basically joined the timeline at Saturday Night Fever and Studio 54. And that was 40 years ago. Things were just different."

"I don't believe I'm a racist, and I am not a homophobe," Dahl adds. "And, you know, it’s fairly Kafkaesque in that I don't exactly know how to explain my way out of something that I didn't think in the first place. You know?"

Jackson says one simple gesture would go a long way: an apology.

"I think that that would be a step in the right direction," she says. "I think people will respect that."

But instead of apologizing, the White Sox last month celebrated Disco Demolition Night’s 40th anniversary. There were commemorative T-shirts — and Steve Dahl threw out the first pitch.

But he says he’s now aware of why some feel Disco Demolition Night was an affront.

"I understand it, and I'm sorry if that's caused you harm or has hurt you in some way," Dahl says. "That's about all I can do."

Dahl has trademarked the phrase "Disco Demolition." So what if someone asked him to do another Disco Demolition Night today?

"You know, I would say, ‘I don't know. That doesn't seem like a good idea,’ " Dahl says. "Because, I mean, based on all that knowledge that I have now of how it affects people and upsets people and whatnot, it doesn't seem cool, I guess."

"Disco is an awesome music," Jackson says. "It espouses love, and it has a lot of energy. And why would anybody hate it?"

Dave Hoekstra’s book is "Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died."

This segment aired on July 13, 2019.