Advertisement

A Cautionary Tale: Spanish Flu And The 1919 Stanley Cup Final

Resume

Kevin Ticen is a former minor league baseball player. And he says he didn’t know much about hockey. But, while researching a book about the 1917 Stanley Cup Final, Kevin came across another story, about the 1919 championship series.

"It was just a weird anomaly," Ticen says. "It was kind of a cute little side story."

In recent weeks, Ticen has found himself thinking back on that story, again and again.

"All of a sudden it's relevant," he says. "As this coronavirus started to spread, I definitely was looking at it thinking, 'This is eerily similar.' "

KG: Let's start at the beginning of this story that you researched. And I suppose in many ways it begins towards the end of World War I with what was called the Spanish flu. So tell me about that pandemic. When did it start? How was it spread?

KT: So, it starts in the spring of 1918. So, it starts a little bit earlier than the end of the war. But the biggest explosion certainly is in the fall of 1918. And I think that's when it's most lethal, right? And so you have all the soldiers returning home from all over the world, and they all return home to huge parades and public gatherings. And, you know, a lot of these guys are infected with the Spanish flu, which is the H1N1, right? So it's the swine flu that we had 10 years ago. Then there was no herd immunity to it. There was no vaccine to it. There was nothing. And it spread rapidly.

KG: And by October of 1918, Seattle had pretty much shut everything down, right?

KT: Correct. Yeah, that's correct. Schools had shut down. Bars and restaurants had shut down. Public gatherings had shut down.

KG: That sounds really familiar.

KT: Absolutely.

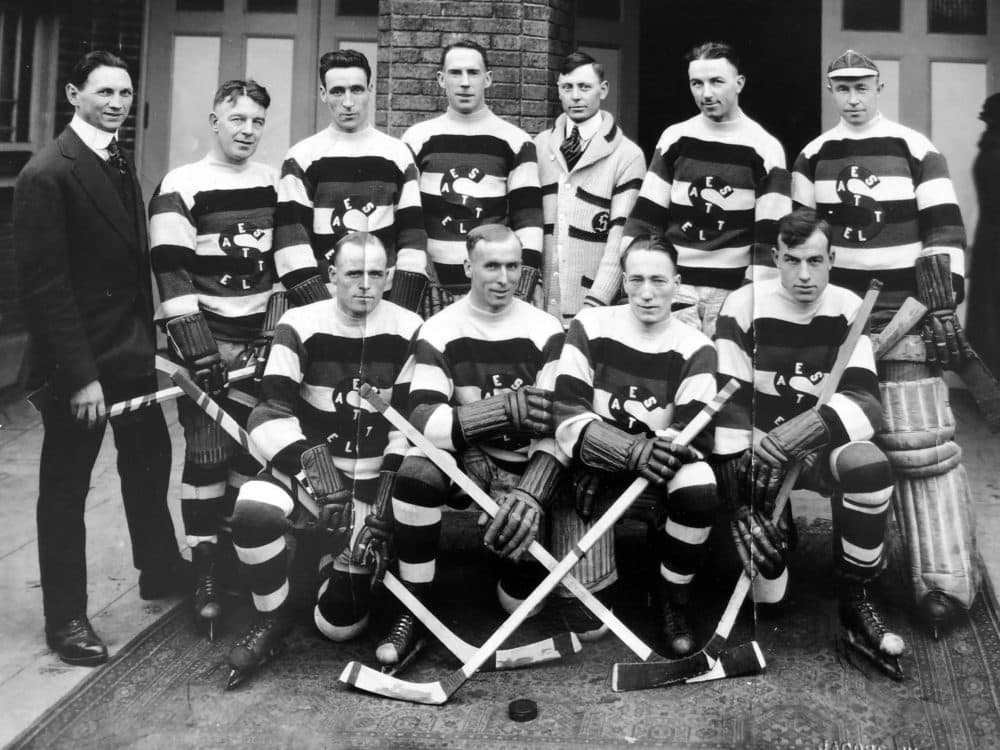

KG: But in January of 1919, those restrictions were lifted. Bars and restaurants were back open. Schools were back in session, and the Seattle Metropolitans were back on the ice. So tell me about the Seattle Mets.

KT: So there's two leagues back then. It's similar to the American League and the National League in baseball, right? So you have the NHL, at that point, is the East Coast league. And the Pacific Coast Hockey Association is the West Coast league. The Metropolitans and the Vancouver Millionaires are, you know, widely regarded as the two best teams out West. And I think the Metropolitans were probably the better of the two teams.

KG: That season — that hockey season started. And it seems like it was a rather short season because two months later in March, the Stanley Cup finals were set. And it was going to be the Seattle Mets and the Montreal Canadiens. And it was a five-day train ride between those two cities, so all five games were to be held in Seattle.

Seattle Daily Times, March 17, 1919: "A mad scramble for world series of hockey tickets, that's what's going on now at The Arena. At 8:30 this morning fans were lined up for blocks in the pouring rain waiting for the seat sale to commence, and the office didn't open until 9:00."

KG: Seattle fans were pretty excited, right?

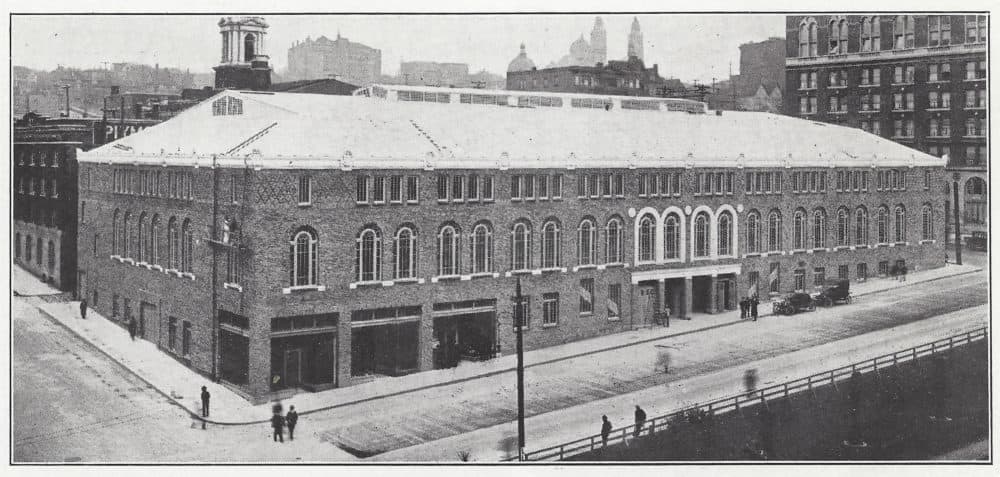

KT: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the arena in Seattle held 2,500 people, and they were packing it with 3,500 for these games. You know, they're standing room only. There's kids up on the roof looking through skylights and looking in the transoms over the doors. And, yeah, it was a really exciting time and really had this populace that needed something to celebrate, right? The war had been devastating, and this virus had been devastating. And it was finally something everyone could rally around and celebrate.

KG: In describing the two teams, the Seattle Daily Times noted that the Canadiens had the weight advantage over the Mets. But they also pointed out that "Bad Joe" Hall, at just 165 pounds, was still "a factor to be reckoned with at all points in the game." So who was "Bad Joe" Hall?

KT: Yeah, so Joe Hall's sort of the first enforcer in hockey. The thing that's interesting — he's a really skilled guy. He's a defenseman. But he's one of those first sort of nasty players that will take your head off if you're not looking. And he was widely respected. You know, he was the guy that — he's friends with all of them. You know, I think on the ice, everybody hated him and hated playing against him. And off the ice, they all loved him.

"The war had been devastating, and this virus had been devastating. And [the Stanley Cup Final] was finally something everyone could rally around and celebrate."

Kevin Ticen

KG: So game one, the locals had the advantage, to say the least.

Seattle Post Intelligencer, Thursday, March 27, 1919: "Skating rings around the Flying Frenchmen, Eastern champions the Seattle Metropolitans put the skids under the Montreal squad in the first game of the world's hockey title series at the local Arena last night. ... The final score was 7 goals to 0, with the Seattle men on the long end of the count."

KG: What happened in that game?

KT: Yeah, so again, like I said, it's sort of the American League and the National League, and so there's slightly different rules. So the West Coast league has seven on the ice. They have a position called the rover. The East Coast league has six. There's forward passing in the West, there's not in the East. So Games 1, 3 and 5 are played by West Coast rules and 2 and 4 played by East Coast rules. And West Coast rules favor athleticism and speed. And it's more of a flow game. And, you know, the East Coast game is more individualistic.

KG: So, the two teams split those first three games, kind of according to whose rules were in use. Game 4 is where things start to get really interesting. So describe Game 4 for me.

KT: The game goes into two overtimes, and players start collapsing on the ice at the end. You know, they get a standing ovation from the crowd, but they come in and decide they can't keep playing, and they declare it a tie. And at that time, they think that it's just exhaustion. And it's interesting. The game is widely considered the greatest game ever played, at least of that era.

Seattle Post Intelligencer, Thursday, March 29, 1919: "They may be playing hockey championships for the next thousand years, but they’ll never stage a greater struggle than that which held 4,000 spectators spellbound last night."

KG: As entertaining as it was, it really messed up this schedule of the Stanley Cup finals, right?

KT: Absolutely. So the presidents of both leagues, Frank Calder and Frank Patrick, decide that they are gonna replay by Eastern rules and that from now on they'll play until there's a winner. And so Game 5 is played with Eastern rules. The Metropolitans go up three goals. All the fans in the arena think that the game's over. And again, exhaustion starts to kick in, and guys start to collapse on the ice again.

And this game again goes into overtime, and the Canadiens win. You know, and I don't think the Metropolitans are that stressed about it. I think they know that Game 6 is gonna be played by Western rules, and, you know, they wake up the next morning, and life's completely changed for them.

"[The players] wake up the next morning, and life's completely changed for them."

Kevin Ticen

KG: OK. So each team has now won two games. That Game 4 tie has forced a deciding Game 6. And it's pretty clear at this point that the players are under tremendous strain. The Seattle Post Intelligencer printed a listing of the injuries. And, well, the injuries — a lot of them are hockey injuries.

Seattle Post Intelligencer, March 31, 1919: "Seattle: Rowe, wrenched ankle; Foyston, torn tendon; Rickey, cut on leg; Walker, bruised leg; Wilson, fever.

Canadiens: Hall, high fever; MacDonald, high fever; Berlanquette, cut on lip; Corbeau, sprained shoulder."

KG: But there are a number of players who are listed as having fever or high fever. And that sounds remarkably like, not exhaustion, but the Spanish flu. Did the newspapers pick up on that? That these are not hockey injuries?

KT: I mean, maybe they did. And maybe they're trying to avoid striking up fear again. But, you know, from everything that I've seen, nobody picked up on it until the day after Game 5's played.

Seattle Daily Times, April 1, 1919: "Influenza has within the past 48 hours laid out five of the Canadiens."

KT: Two Metropolitans, both head coaches, they all wake up with, you know, scary fevers, like, 103-104 degree temps. And at that point, the Canadiens don't have enough players to put a team on the ice, and they offer to forfeit the series. Pete Muldoon, the head coach for the Metropolitans, won't accept winning, you know, not on the ice. And so he declines the forfeit. As that's all happening, the health department swoops in and cancels the series.

They talk about moving it to Vancouver a little bit. And then they talked about moving into Montreal. They talked about waiting a few weeks. They ultimately just decided that this series goes down as a tie.

KG: OK. So, four days after the game was called off, Joe Hall died. What was the reaction to that news?

KT: It was, you know, horrible, right? It's a guy that was friends with all the players. You know, he's 37 years old. He has three young kids. He lived in Vancouver, British Columbia. So, you know, he was in some ways a local. Both teams went up for the funeral, and a very, very, very sad time.

KG: And while the others recovered, they didn't all come out of this unscathed, right?

KT: Yeah. So George Kennedy, the owner of the Canadiens, he recovers from the short-term effects of this flu. But, you know, he has a pretty severe health complications for the last two years of his life. And he passes away.

And Pete Muldoon — who, you know, is the Metropolitans' head coach, right? And this is a guy that was a professional boxer, he was an ice dancer. Really, really super healthy guy. And he ends up having a heart attack 10 years later and dying at the age of 41. And again, two small kids. And there was a lot of thought then that he never fully recovered from the Spanish flu, that it potentially had weakened his heart. I read a stat that Spanish Flu pandemic cut the life expectancy in America by 12 years.

KG: Wow. So, the 1919 Stanley Cup Final remains the only time a U.S. major professional sports championship ended with co-champions. You’ve gotten to spend, as I understand it, a little bit of time with the Stanley Cup itself. How is that year inscribed on the Cup?

KT: Yeah, it says: "1919–Montreal Canadiens–Seattle Metropolitans–Series Not Completed."

When I first started researching the book, I wasn't sure, you know, if people cared about hockey. I wasn't sure if the Stanley Cup was, you know, even a thing that was famous back then.

And it certainly was. It was very, very important to the players, to the media, to the fans. You know, they were all very passionate about it. The city really wanted to win. The players really wanted to win. And they just ultimately couldn't make it happen.

KG: What lessons do you take from this story?

KT: Yeah, I mean, I think — you know, one of the biggest things is just, as you see the media reports and as this thing unfolds — I think one of the biggest points of fear is, you know, that we're in uncharted waters, right? Nobody's seen this before. It certainly has never happened in our lifetime, but it has happened. You know, there are a lot of lessons that, you know, our government and the health department and our sports leagues, you know, can draw from that experience.

And like the league came back, right? All the sports came back. The 1920 season starts, you know, just a little bit late. You know, it wasn't like it was this lingering hangover that took years and years and years for society and our economy and all those things to bounce back. You know, it happened rapidly.

So for me, I draw a lot of hope from that and parallels from that. That we will get through this, and things will bounce back quickly and our economy will be humming again. Our restaurants will be full and our arenas will be packed.

KG: So when you hear people complaining that all of their favorite sporting events have been taken away, what do you want to say to them?

KT: You know, I mean, this is sort of a bad answer, right? I mean, I was a professional baseball player and a college baseball coach. And, like, it's tragic. I feel horrible for, you know, the college seniors and high school seniors that have lost, you know, something special, something that can never be given back to them.

But also, look at it like this, right? So, let's hope that this thing doesn't get anywhere near what Spanish flu pandemic did, right? And I don't think it will, but it was like 500 million that were infected. And, you know, roughly 50 million died. And if you apply that to today's population, right, that's 2.6 billion that are infected, and, you know, roughly 230 million that die. And it's horrible, right? I'm completely willing to give up my sports so that 230 million people don't have to die.

I think that we can all come together as a community and hopefully continue to support our franchises and our businesses and all those things and get through this and have a great summer watching sports, hopefully.

KG: You said that was gonna be a bad answer, but I don't think it was a bad answer at all.

KT: I mean, I just, like — I struggle when people are complaining about it.

KG: Thanks so much for this. This has been really great.

KT: Yeah. Thank you for doing it. I think it's a message that needs to get out there.

Kevin Ticen’s book is "When It Mattered Most: The Forgotten Story of America's First Stanley Cup, and the War to End All Wars."

This segment aired on March 28, 2020.