Advertisement

Lou Ureneck Rebuilds Himself, And A 'Cabin'

Resume

Lou Ureneck was stuck. Stuck after a string of personal setbacks. Stuck without a job. Stuck in the city.

Ureneck was not lost, though. He was a nature person, so he went back to his roots. He and his younger brother, Paul, built a cabin in the hills of western Maine. What follows is a story not just about building, but of self-discovery, familial re-connection and a life reborn.

Inspired by Ureneck's popular New York Times blog From The Ground Up, Ureneck's "Cabin" is a moving story about a man coming un-stuck.

Guest:

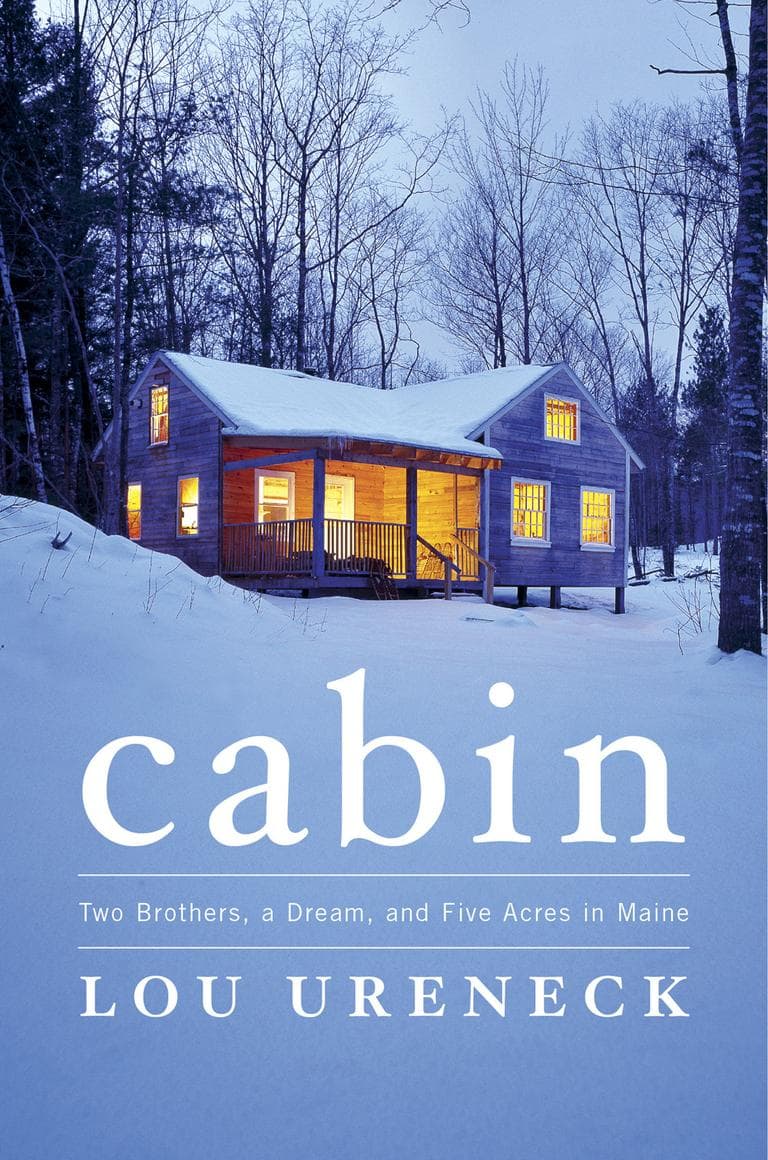

- Lou Ureneck, author, "Cabin: Two Brothers, a Dream, and Five Acres in Maine"

Excerpt: Cabin: Two Brothers, a Dream, and Five Acres in Maine

(PDF)

The Urge to Build

The idea had taken hold of me that I needed nothing so much as a cabin in the woods — four rough walls, a metal roof that would ping under the spring rain and a porch that looked down a wooded hillside.

I had been city-bound for nearly a decade, dealing with the usual knockdowns and disappointments of middle age. I had lost a job, my mother had died and I was climbing back from a divorce that had left me nearly broke. I was a little wobbly but still standing, and I was looking for something that would put me back in life’s good graces. I needed a project that would engage the better part of me, and the notion of building a cabin - a boy’s dream, really - seemed a way to get a purchase on life’s next turn. I won’t lie. I needed it badly.

So, on a day of warm September sunshine in 2008, after having bought a piece of land in western Maine, I stood in a corner of my brother Paul’s suburban backyard in Portland, and examined a stack of lumber I had dropped there more than 10 years earlier. I had to stomp down the weeds with my size-ten brown-leather brogues to get to it. I hadn’t yet bought a pair of work boots. I was dressed for the classroom where I now earned my living, disguised as a college professor: khaki trousers, button-down cotton shirt and semi-round tortoise-shell glasses. I confronted the wood; or maybe, as a symbolic artifact of an earlier life, it confronted me. It was a temporary standoff with the past. Piled chest high, the wood made an incongruous sight among the neighborhood's turquoise swimming pools, over-sized gas grills and slumping badminton nets. It resembled nothing so much as a heap of old railroad ties dumped by the side of the road.

I brushed the rough surface of the wood with my hand and pressed a thumbnail into its pulpy flesh. It was spongy: not a good sign. A few of the boards showed sawdust and smooth channels that were the work of carpenter ants. There were many more pieces — heavy posts, big square beams and long silvery rafters with bird’s-mouth mortises — that had come through the years of sun and snow mostly sound. I couldn't help feeling some affinity with the wood: a little weathered but still mostly intact. This was what I had hoped for on the drive up from Boston, where I lived and worked. I had counted on salvaging enough lumber from the pile to form the frame of the cabin that already had taken shape in my mind.

Paul stood with me in his backyard. He was less sure about the wood.

"I don't know," he said. "A lot of it’s wet, maybe rotten."

Paul is an experienced and methodical builder. He typically works with architects, engineers, cranes and shipments of steel. He was the construction and project manager for a commercial real-estate company in Portland; its vice-president, in fact. He is a non-conformist in other parts of his life — a big man with a thick mustache, he drove a Harley-Davidson motorcycle wearing a sleeveless undershirt, open leather vest and a head kerchief tied tightly above his ears for a helmet — but he was cautious in matters of construction, the equivalent of the prudent and spectacled accountant. He applied conservative principles to the building of things, and he was exercising his professional caution on my woodpile. He might as well have been a banker sniffing weak collateral. I, on the other hand, was determined to work up the cabin from the old lumber, which would seriously reduce the project’s cost and give me a rustic shelter that was an appreciation of the beauty of wood, and I wanted to get started right away. I was feeling the burden of his skepticism.

"The roof is going to have to carry a big snow load in those hills," Paul said.

I could feel him inching closer to the saying of what he was actually thinking, which was that I should forget the wood pile and have a fresh bundle of 2x4 studs delivered from the lumber yard. That after all was the sensible thing to do: new lumber, new windows, pre-hung doors and pre-fabricated roof trusses. We could hire some help, engage subcontractors for the plumbing and electrical and have the cabin up in a few weekends. I would summarize his attitude as, “Let’s make this easy and get to the part where we sit inside and enjoy the place.”

Instead, I wanted to construct the cabin with these big woebegone slabs of wood in the old timber-frame method of building a barn, which meant employing, as much as possible, old-fashioned wood joinery rather than nails. It would hold together in much the same way as a chest of drawers assembled in a furniture shop. I wanted a place with some heft and tradition - a place that could make a natural and authentic claim on a piece of rugged Maine hillside. I didn’t want a vacation home; I wanted a cabin. The rough-sawn and weathered beams, as I planned it, would be exposed inside the cabin just as they would be in a barn or backwoods Maine camp, and it would be rough and raised-up from local materials, and it would be all the better for requiring the expenditure of time and skill with a mallet, wood chisel and framing square. And I wanted for us to do it all ourselves.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Cabin: Two Brothers, A Dream, and Five Acres in Maine. Copyright © Lou Ureneck, 2011

This segment aired on September 27, 2011.