Advertisement

A Tribe Called Us: E.O. Wilson On Human Evolution

Resume

This story is about a couple of why's. The first why, the great, big why is: Why are people good?

"Group selection, or the intense competition between groups helped develop the best angels of our nature," says Edward O. Wilson. "Our ability to form alliances, show mercy, compassion, risking our lives for someone not related, the best qualities."

We're hardwired for morality?

"Yes, we are."

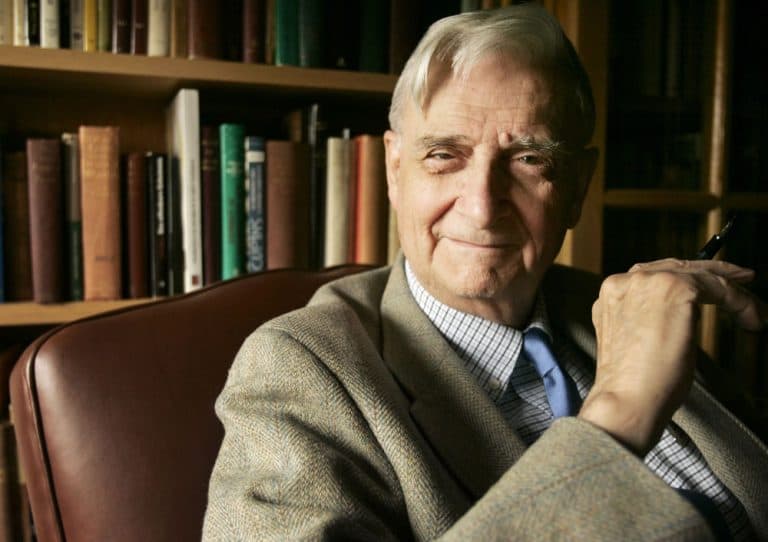

Wilson is professor emeritus at Harvard University. A giant in science. The father of sociobiology. The fellow who revealed the magnificence of ant society. The man many consider to be Charles Darwin's heir. At an effervescent 82, he's written a new book, entitled "The Social Conquest of Earth," in which he says that morality, religion, creativity, all that makes us human is fundamentally biological in nature due to a phenomenon called eusocial behavior.

"You have a group of individuals remaining together over more than one generation, rearing young and dividing labor. That includes some degree of altruism between more reproductive individuals in the same group as less reproductive individuals," Wilson says. "I've spent a good part of my life studying the social organization of animals, and [eusocial behavior] has been achieved about two dozen times."

Remarkable.

Wilson says morality, religion, creativity is fundamentally biological in nature due to a phenomenon called eusocial behavior.

Of the thousands of species ever to roam the earth, we are one of just two dozen to form highly cooperative societies in which the engine of evolution is not fueled by the drive to see your direct genetic offspring survive. No. That is called kin selection. Wilson says we eusocial human beings are compelled by something bigger, by group selection, no matter how many, or how few, members of the group share your DNA.

"We are group crazy," Wilson says. "That is what we must do all the time. We must communicate and form bonds...we became socially intelligent when we came together in the bonding situation of a nest, a campsite. So, to read one another's intentions, to cooperate is something that works at the individual selection level and it explains an awful lot about human behavior."

This is astonishing. If you're a scientist, you're now thinking, "Wait, what? Why? This makes no sense." A half century of biological research points to the supremacy of selfishness of King Gene. Kin selection theory works because we know parents will instinctively lay down their lives for their children. How could the good of the group ever overwhelm that?

It turns out that the two dozen eusocial species became adept cooperators due to a combination of thousands of generations of genetic adaptations that led to the formation of nesting colonies. (Think ants, bees, wasps, the naked mole rat.) The tendency was cemented in human evolution when human ancestors came together in early tribes who hunted, foraged and lived cooperatively.

Layer upon that the spectacular growth of the human brain, the emergence of imagination, morality and religion, and Wilson says you begin to see how the biological need to form groups gives rise to some of our most powerful positive and negative behavioral instincts. The urge to be a member of Red Sox Nation? A soldier throwing himself upon a grenade to save his platoon? The fight for Civil Rights? War itself? All part of the basic genetic drive to put the "group" first.

Wilson's theory has rankled the scientific community, in part, because he was one of the original champions of kin selection theory, or that evolution puts "family first." Many biologists also claim that Wilson's new work ignores more than 50 years of research that supports kin selection theory.

When Wilson and several Harvard colleagues first published their findings in a 2011 issue of the journal Nature, more than 100 scientists submitted a response. One scientist wrote: "[Wilson is creating] a conceptual tension which, we argue, is unnecessary, and potentially dangerous for evolutionary biology."

"That kind of response may be a suggestion that we were right," Wilson says. "Science is not settled by polls, and it is not settled by emotional response."

It may be churlish, but one take on the controversy could be that by being so outraged, this group of scientists is inadvertently proving Wilson's theory. They are reacting because he has challenged their body of work, their group. Put another way, this is how science itself evolves, through civil disagreement, the competition of ideas, the endless testing of new theories.

But what can humanity itself take away from Wilson's idea that we are eusocial beings? If he's saying we're hardwired for morality, are we also hardwired for war? Will conflict be an eternal part of the human condition?

"I don't think we can deprogram ourselves from our impulses," Wilson says. "Let's call this a pathology we've inherited. To diagnose it correctly through self-understanding is to know what we're doing. We're not just obeying some deity that will lead us to paradise. To diagnose the flaws of human nature correctly is the first step to a cure."

Guests:

- Edward O. Wilson, professor emeritus at Harvard University, author of "The Social Conquest of Earth"

This segment aired on April 11, 2012.