Advertisement

'Cuz': Two Lives, Split By Society

Resume

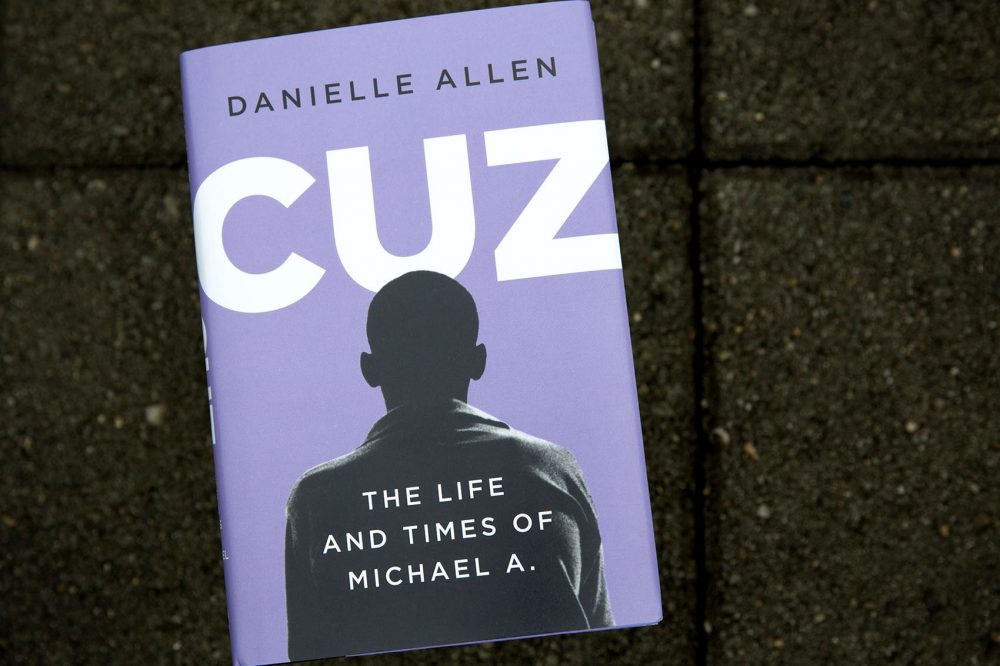

Danielle Allen has written one of the most important books published in America in the past five years. She's a Harvard professor, and director of the university's Safra Center for Ethics.

It's called "Cuz: The Life and Times of Michael A," and it's the story of her beloved cousin, Michael. They were very close.

But while Danielle went to an Ivy league college and propelled herself into a fast-rising academic career, Michael was arrested for the first time when he was 15 years old. He spent his teen and early adult years in prison, 13 years overall. And when he got out, he was never really free.

He died violently in 2009, at the age of 29.

Two cousins, whose lives were once on similar paths, diverged dramatically — but that fork in their road was put there by us, by American society, and a culture that in the 1990s believed young black boys were "super predators," amplified the war on drugs, imposed mandatory minimum sentences, locked up an entire generation and threw away the key.

So while this is the story of Michael and Danielle Allen, it is also our American story. Because as Danielle Allen writes, Michael was just "one of so many millions gone."

You can read an excerpt of "Cuz" here.

Guest

Danielle Allen, the director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University, and Harvard's James Bryant Conant University Professor. Her new book is "Cuz: The Life And Times Of Michael A." She tweets @dsallentess.

Interview Highlights

On who Michael Allen was as a kid

"He was just such a joyful person, so bright, so energetic. He had this gorgeous smile, it was always the first thing everybody said about him, this gigantic smile that lit up half his face. He was a motormouth, incredibly talkative. He was just beloved, the baby of a huge extended family and just adored. We were close, a sort of a subset of cousins that spent a really big amount of time together."

On when their lives drifted apart

"It's a big American story because my dad and his sister Karen grew up on this tiny island off the coast of northern Florida. It was a Southern, African-American fishing community. My dad ended up in Claremont, California, as a college professor. Karen ended up in Los Angeles as a single mother having left an abusive relationship and worked her way up as a nurse. I was a faculty brat in a college town. Michael was growing up in the city, but they spent a lot of time with us. They lived with us sometimes we always were gathered together on holidays, lots of time playing outside in the summer.

"The real shock in Michael's life came when when he was 10 his mother met somebody and thought she had the prospect of a happy life, a marriage and stability. It was just the most tragic decision because the person she married turned out to be violent. The family moved five times in five years. Michael was changing school constantly. And that was exactly the same time I was going off to Princeton. That's sort of when they diverged, when his life got caught up in this terrible marriage of his mother's, and I was headed off to a liberal arts education in beautiful surroundings.

"So they're in Southern California, and those were the years between 1992 and 1995 when everything was happening. It's basically the peak of violent crime in Southern California at that point in time. Imprisonment had jumped tremendously. The issue of gangs and drug trafficking was on everybody's mind. You had the Los Angeles uprising during this period.

"At that point Michael was this free floating agent, he didn't have a community, he didn't have a world. He landed in the middle of an incredibly difficult rough Los Angeles. That was a very dangerous combination. And it's exactly when all the pieces of Michael's life sort of gave way."

On Michael's arrest at age 15

"It was a Sunday morning in September 1995 and Michael had a gun. He'd acquired it a couple of weeks earlier, we don't know exactly how. He came upon a guy, 44-year-old guy cleaning a Cadillac in a carport in an alley behind this apartment building.

"Michael came up, told him to hand over his watch, guy did. Wallet, guy did. It was empty. Michael threw it back and said, 'I'm taking the car.' And then his victim lunged for him.

"Michael had his gun pointed at the ground the entire time. The victim lunged for the gun, got it, and shot Michael through the neck. And that was the end of his attempted carjacking.

"The police came, ambulance came, and they took Michael to the hospital and on the way there he both confessed to what he'd just done. But he also told the police that he had robbed three people the previous day in the same block and one person a week earlier in the same location.

"It was a spree. You have to say that about that week. It came out of nowhere, in that that there hadn't been anything like that in his experience before then. He had never been a violent person. So it was it was a very surprising episode."

On Michael potentially facing life in prison, under California's Three Strikes Law

"The judge told him that he had to make a decision about his plea. Was he going to plead guilty or stand trial? The judge said, 'if you stand trial and you're convicted on all four of these charges, that will trigger the no strikes law, that will be 25 years to life that you're facing in sentencing.'

"The framework of the three strikes law was working to frame conversations about plea deals basically. Being presented with what looked like a sort of 25 to life option on the one hand, since he'd already confessed to everything. Or the plea deal, he took the plea deal."

On the decision to take a plea deal

"Michael himself couldn't choose. I think for my aunt, that was probably one of the most if not the most painful moments in the whole experience. And she went outside the courtroom and prayed and prayed and prayed some more. That's how she tells the story. And God told her Michael would get seven years. So she went ahead and said that they should accept the plea deal, and instead he got 13 years."

On the process of writing the book and reliving these family experiences

"It was hard. No question about, it but it was also good. We hadn't talked about what happened to Michael. This is a terrible thing that this kid, an adolescent, you know, dealing with all the ordinary torments of adolescence, was flirting with the most dangerous stuff in the city. And we didn't see it. It wasn't until I was working on this book you know, sort of more than 20 years after he was arrested, was the first time that his mother realized he'd been getting involved in gangs. It was the first time I realized he'd been getting involved in gangs. That for me is one of the hardest and most painful parts of it all is to try to figure out why is it that we didn't see? Why is it that adults don't see the kind of trouble that kids are getting into?"

"We who are in prison had to answer for our sins and our lives were taken from us. Our bodies became the property of the State of California. We are reduced to numbers and stripped of our identity. To the State of California, I am not Michael Alexander Allen but I am K10033." — Michael Allen

On Michael's writings while in prison

"He was astute, he was smart, he could express the most complex emotions and give voice to experiences that are unimaginable for those of us who've never been inside a prison. Let me just go ahead and read a little bit from his essay about 'Dante's Inferno.'

My hell is no longer demonstrating what I am capable of doing in order to survive. It has become what I can tolerate and withstand in order to live. I cannot help but to judge those around me. I am one of them, but we are far from the same. Like Dante, I am cursed with a spirit of discernment which allows us to see the truth for what it is. There are most whom I despise who are truly sick beyond healing and they should never leave this place. Then there are those who await to fulfill their destiny. I see in them a sincere and apologetic heart for their ill misdeeds. They are the ones who will change the world positively or positively change someone's world. Hell cannot hold the latter of the two opposites but in time it will only spit them back out into society to do what is right. The hell that I live in cannot hold Dante. Hell can test and try one's self but it cannot hold Dante and it will not hold me. In the Inferno, the dead are trapped forever. Surely the biggest and most important difference in the Inferno and my hell called prison is that I have a way out.

On Michael having a way out

"His life changed in effect inexorably that day when he was 15 and he tried to take somebody's car with a gun. Inexorably and irreversibly. But that's what you realize is when somebody has been in prison for 11 years and that's their social world and life, to ask them to start fresh is to ask them to give up every meaningful connection that has made their life bearable for the last 11 years. And that is a demand of surpassing difficulty."

On the context behind Michael's time in prison

"This was a period where the whole criminal justice system had shifted gears from an approach to rehabilitation, trying to get people ready to reenter society, to a pure deterrent framework. Deterrence is about focusing on an aggregate level of crime, bringing it down, losing sight of the individual. The use of mandatory minimum punishments for example is a very good expression of that deterrent philosophy and you get a whole lot of just individual cases of injustice.

"But because of this focus on deterrence the goal was to make prison as bad an experience as possible, which I think people have really succeeded at doing whether achieving deterrence is different question. Educational offerings were stripped out of prisons in the 1990s and both states and federal government withdrew funding to support prisoner education. But Michael was hungry for college. He had always been hungry for college. So we got him enrolled in correspondence courses through Indiana University."

On serving time in prison as a teenager, and the milestones he experienced

"First long-term family separation. So when he was 17, he was moved from the juvenile into the adult system and he was moved to a prison at the Oregon border, which is crazy. It was so far away, his mother couldn't visit him. He spent his first six months in adult prison without a single family visit. Other rituals are, first 'administrative segregation,' as it's called, which is a label for solitary confinement. First racial melee, first sodomization.

"When I was writing the book one of the things that was very important to do was to try to juxtapose different teenage experiences, in particular mine and my cousins' and to show the things that are similar about them. The loneliness, the insecurity, the first experiments with intimacy, and relationships and things like that. The effort to carve out your own space, the desire for mobility and freedom and so forth. And then just to show how you know this is a teenager going through all those experiences of an ordinary teenager but in this cauldron of prison that is so violent and so full of brutality. And then to ask the question of what does that mean, what kind of development can we expect for a young person in that sort of situation? It's just crazy to think."

On writing about visiting Michael in prison

"I'd written a chapter about visiting that tried to go to the just the detail of the place, the people who were there, the things you saw, the things you smelled and so forth. But if read it, it's 'you' see this, 'you' see that, 'you' do that.

"And my editor, every time I'd send the manuscript in, he was sort of doing line editing. But the one structural thing he would say, 'you're not in this chapter, Danielle, you're not in this chapter.' And I didn't know what he meant. I'm describing everything I saw. Finally I realized what he meant which is that in the book and that up until that point, I had been using I. I had been saying, I felt I did X and suddenly in this chapter I switched to you. And that was like this huge light bulb going off that even at this point you know, many drafts into working on the book, I had not been able to break through a certain kind of repression to say: 'I was in prison and here's what it was like for me.'

So I wrote that chapter again."

I will have to try again to describe what visiting Michael meant to me. The fact that I told the story as an academic already tells you everything you need to know. That wound of visiting Michael in prison goes so deep that somehow even in writing this book I have found it hard to own up to one simple fact: I went to prison. I was in prison. No, I don't mean that I've been arrested or convicted of a crime. I have avoided that because thus far in life I have had that combination of goods the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle thought was necessary for a happy life — resources, decent character and luck. But no, I was not in prison as a convict. And this is thanks to my father, my mother and my God. Yet even as someone who could come and go, I felt the prison mark. Its branding fork. I felt it in my soul, even though all I was there was a day's sojourner." — Danielle Allen.

On the duality felt by Danielle Allen

"I mean you know the whole point of being an academic is that you don't do this kind of thing. So I'm grateful to Michael because one of the things I've learned from doing this is just how important it is ... Even as an academic to put head and heart together. For instance, these questions of criminal justice are questions that you can approach from an academic perspective, but knowing why they're important to approach and believing in one's heart as a motivation for research questions, why do you choose particular research questions, that super important. But it's fine to unify head and heart, even in the academy. And I think I've learned that thanks to Michael. And that's also something I'm trying to share."

On the support Michael had on the outside

"I was with Michael's mother on his release day and that was the beginning of summer of intense effort, as we worked together to try to give him a foundation from which he could build something meaningful and valuable to him.

"He had this big family it had people with financial resources, people with educational resources in it. And we had a lot of things to bring to bear on trying to help Michael. And really you know remarkably within six weeks of his release in 2006, he was enrolled in school, he had a job, and he'd been offered an apartment to live in.

"He'd fought wildfires in California in prison and he loved it. That was this bright spot, an opportunity for resilience and growth and something positive in the midst of that prison experience. He going to work at Sears and go to community college and do Fire Technology Program. And he and I were spending every day together putting these pieces together.

"But you know, who wants to rent an apartment to somebody who's just got and gotten out of prison after 11 years for attempted carjacking? I mean that's a pretty big ask.

"So you can't just go into that without a lot of care and effort. You have to find a good place, and you have to be clear in your own mind. We had to be clear, I had to be clear, Michael had to be clear that it was right, that we could do right by the people who were there, that he could live well, that he could be in control of his life, that I could vouch for that.

"And it takes a lot of preparation to feel ready to walk up to strangers and say 'I can vouch for my cousin, who's just been in prison for 11 years.' I could, with complete confidence. We did that together. The two women who were there talking with us, they trusted us. I will be eternally grateful for that act of generosity."

On Michael falling in love in prison and taking that connection outside of prison

"It's the connection that he can't renounce and that means he was deeply and permanently connected to a person he loved and who loved him, but who was also violent. And their relationship had violence in it, and it ended in his death.

"At the time, when he was thinking about whether to take the apartment, I could not understand his thinking, I had no idea what was going on, I could make no sense of it at all. All I knew was at the end of 24 hours he decided firmly that he wasn't going to take the apartment.

"It wasn't until four or five months later when he called and said he was ready to take an apartment and I went to go look at it with him and he said that he and his girlfriend Bree were going to move into the apartment.

"Bree was his girlfriend whom he'd met in prison. So a transgender woman. They'd been lovers in prison. I did not know that they were still seeing each other, that they had reconnected after he got out.

"I suddenly understood that that was his decision making was about that day when he couldn't take that apartment. It was a choice, right then, between Bree's world and the world he had had for the last 11 years, and the world of his family which he'd had too but over the telephone. Not day-to-day in terms of who he was living with, and the prospect of a future of great uncertainty without yet having any concrete definition. And with that choice in front of him, he chose the love of his life."

On the lessons from Michael's life

"I've been trying to boil it down to just one lesson and I just find it impossible to do. I have a couple.

"One lesson is just that when kids are 10 to 14, they need every adult in their life to be talking to each other. Forget about shame, forget about the conflicts that keep different family members from sharing things with each other, every kid in that hard adolescent transition period needs total openness and a frankness from adults with them making it possible for them to be open and frank also. In my family, we didn't do that. That's, I think, our responsibility in this story.

"Another lesson is that we have really destroyed lives with the criminal justice system. That's a combination of how we think about juvenile justice, how we think about mandatory minimums and what we've done with the War on Drugs, which is to build this incredible world of hypocrisy and sustain an incredibly powerful illegal black market. We really underestimate its power and the general distorting effects it has on society, and especially on youth experience.

"And the last thing, about the question, what's Michael's responsibility? How do we think about that? I think Michael himself took responsibility for his choices, his Dante essay makes that very clear. He understood he'd made the wrong choices and he understood himself to have been motivated by, in his words, greed and lust in that moment when he tried to steal the car. He knew that. And he changed and he had a view about what was wrong with his own decision making. But at the same time that he accepted personal responsibility for his own choices, I think as a society, we also have to accept responsibility for the fact that we present young people with vastly disparate degrees of difficulty on the life courses in front of them.

"Yes, even in the most difficult circumstances some people can master the degree of difficulty and overcome, but many people can't. And when society is leaving young people in poverty, leaving young people without access to good education, we have to recognize that we are creating the patterns, the degrees of difficulty that they're obliged to confront."

On the questions Danielle Allen asks herself

"This book was driven by 'why questions.' It's called 'Cuz,' which means cousin, but it also means because.

"I had been tormenting myself with 'why questions.' They weren't so much, 'why couldn't I save him?' Although they were 'Why did the process of trying to help him go wrong? Why didn't it work? Why did he end up dead with such promise and so many people who loved him?' And for me the most important 'why question:' 'Why did he end up on that street corner, holding a gun, trying to take somebody's car, given he had this extended family that loved him, was committed to him, and had resources?'"

"Why can't we do better for our kids? I know we can. Everybody knows at this point, the stunning facts about incarceration in America. That we have 5 percent of the world's population, but 25 percent of the world's incarcerated population, and 2 million people in prisons. I just want to implore people to realize that when you've got 2 million people in prison, every single one of those people is connected to 20 other people, 40 other people, 50 other people.

"Every single person in prison represents a huge impact on our society. More on the order of 20 to 60 million people being impacted in any given year on account of this. The ripple effects of this are just tremendous. I think we really have to come confront the damage that we've done to our own society with this approach to criminal justice."

On what writing this book has done for Danielle

"I answered my questions. So I have a certain kind of peace that comes from not constantly beating yourself with these questions. I am deeply grateful for that and I'm deeply grateful to my aunt for having given me permission to do this. I had to start by asking her if I could do this. And I do have my answers now."

This segment aired on September 7, 2017.