Advertisement

To See The Future Of Martha's Vineyard, Look To Its Past

Resume

"Relentlessly, and unavoidably, Martha's Vineyard is disappearing."

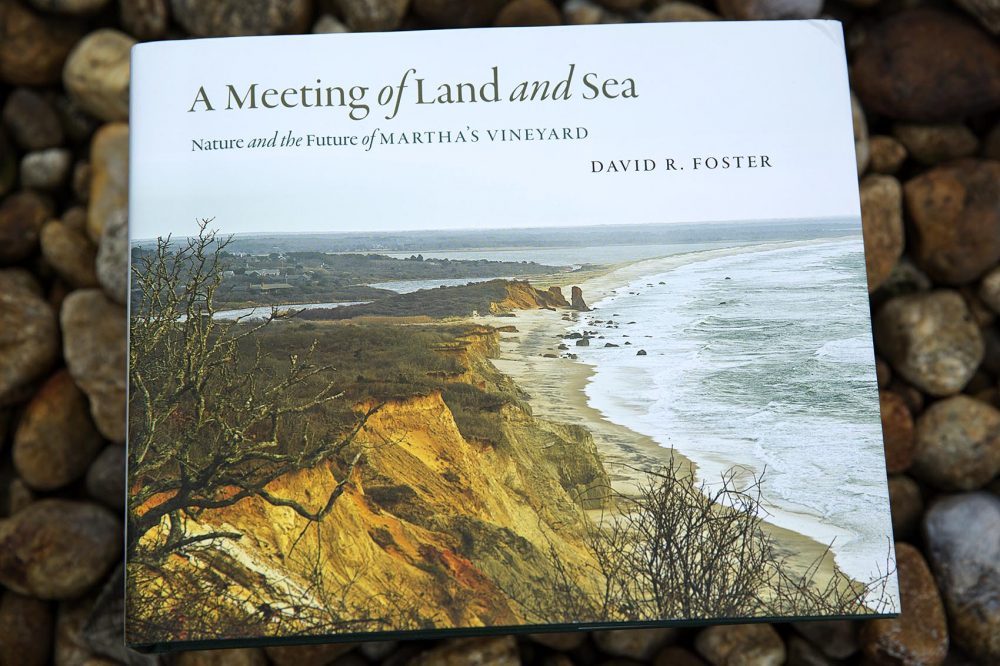

That is how David Foster begins his recently published natural history of Martha's Vineyard, "A Meeting of Land and Sea: Nature and the Future of Martha's Vineyard." In it, Foster looks at the landscape's rising human activity and surprising resilience.

On a recent tour of the island, Foster explained the importance of understanding the rich history of the Vineyard to protect the land.

Looking To The Past

David Foster and I are taking a ferry at the south east coast of Martha's Vineyard to the island of Chappquiddick. Here, there's a dramatic example of the importance of looking at the history of a place to understand its future.

Wasque Point is home to some of the fastest rates of erosion on the eastern seaboard. We walk up to the edge of a sandy cliff. Just beyond the fog we can see the barrier beach — a strip of sand that barely crests out of the water and runs parallel to the shore.

"The water used to wash right up against this," he explains. "This is just pure sand and so every time a wave hit it, it just crumbled." The barrier beach now protects the bluff, but it's only a matter of time.

"When the barrier beach breaks and when there's a big storm this kind of beach disappears overnight."

That was a hard lesson learned for one of the area's most famous pieces of architecture: the Schifter House. The Schifter House used to be on the edge of the bluff, but was moved back as the sand below it eroded away.

"If people had paid good attention to the historical understanding out here, they would've realized how vulnerable it was," says Foster. Had the planners and engineers looked back centuries, to work done by coastal topographer Henry Whiting, they would have seen records calling Wasque one of the most quickly eroding spots on the northeastern coast.

"The people who built the houses here, the boards that allowed them to build the houses here, they were surprised by the erosion," says Foster. "People will be surprised by the next hurricane because we could easily have hurricanes that are much more powerful than anybody has ever experienced. We might be less surprised by if we spent more time looking at history."

Foster says, based on history, we know what will ultimately happen to the Schifter House.

"The beach will move to the North and all the property that this fellow owns will be lost."

A New Plan For Conservation

Back in his car, we drive to one of Foster's favorite places on the island. It's a beautiful scene, with the blues of the water set against the bright greens of lush island vegetation. But Foster likes it for more than its beauty; It's one of the island's great conservation stories. He points toward the pasture land and brush to our left.

"Conservation is not just protecting intact sites," he says, "It's managing sites so that they become even more beneficial for nature and for people."

The land used to be dotted with houses, but they were sold to the Martha's Vineyard Land Bank — a voter-created land agency that helps to conserve the island and protect the environment. Now, the natural ecosystem has returned.

"The tendency in affluent places is to conserve nature or conserve old farmland and kind of freeze nature," says Foster. "Well, you can't freeze nature."

Instead, he says, a better idea would be to put the landscape to its original use, producing food or timber.

"We can learn much more about conserving better and then utilizing nature to our advantage but in ways that respect nature."

Letting Nature Be Nature

Our last stop on the tour is a woods preserve next to the main road that winds around the Vineyard.

Here, he explains, an outbreak of a native caterpillar species defoliated all the oak trees. Then, there was a drought, and all the trees died. The trees lost their branches, their bark, and started to fall over. And yet, it's not an unhappy ending.

"At the same time, [there was an] absolutely phenomenal resurgence of young growth, of new saplings, of sprouts of new seedlings," he says. "And in the intervening time, all the plants that were in the understory have all just flourished."

Blueberries, huckleberries, and raspberries have created a banquet of berries in the forest. Foster says, "It's a perfect example of the way nature copes with what we would perceive as a disaster."

And speaking of disasters, I ask about what the effects of climate change might be in the future on the island.

He says the impacts so far are "relatively subtle" compared to the human activity and development on the island. "It's going to be a long time before climate change has an impact that is commensurate with that."

The best way to deal with the effects of climate change, whether rising seas, strong hurricanes, or defoliated forests, Foster says, is to let nature be nature.

"Nature is actually remarkably resilient, but it's only resilient if we keep it intact."

Guest

David Foster, director of the Harvard Forest and author of "A Meeting of Land and Sea: Nature and the Future of Martha's Vineyard."

This segment aired on September 15, 2017.