Advertisement

Potential conflicts of interest widespread at Mass. special ed schools

Resume

In the affluent town of Sudbury, a special education school funded in large part by taxpayers has been fraught with conflicts of interest and financial mismanagement.

At Broccoli Hall, the head of the private school employs her husband and son, netting the three highest salaries in 2021. Over the years, the family also bought personal items on the school’s credit card, took out advances and inappropriately supervised each other.

Board members overseeing the special ed school had financial entanglements, too, with several securing work contracts with the nonprofit.

Broccoli Hall, which enrolled about two dozen students ages 11-19 last year, isn’t an outlier in Massachusetts. Among the schools the state approves to teach students with special needs, there are widespread potential conflicts of interest, from family hires to deals with board members.

Public dollars, private special education

Of the 76 organizations, a WBUR investigation found nearly three-quarters awarded contracts and jobs to relatives of school leaders or board members from 2019 to 2023. In some cases, the leaders or board members landed their own deals.

The review found dozens of spouses, children and other relatives involved in financial contracts like teaching jobs, IT gigs or insurance deals.

“It seems like an awfully big coincidence that the best person for each of these jobs just happened to be a family member of another person involved with the schools — it just seems statistically highly unlikely,” said Laurie Styron, who heads the nonprofit watchdog CharityWatch and reviewed WBUR’s analysis.

The vast majority of the schools operate as private nonprofits and are required to disclose potential conflicts to government regulators.

Conflicts of interests aren't illegal. But experts say nonprofit board members and leaders should avoid business relationships with the organizations they oversee. Even appearances of conflicts can damage credibility.

"It seems like an awfully big coincidence that the best person for each of these jobs just happened to be a family member of another person involved with the schools ... ."

Laurie Styron

“People need to be able to trust that their tax dollars and other resources are being used by the nonprofit in the best possible way,” said Styron. “And it makes it tougher to do that when people see a lot of nepotism.”

There was also little transparency for how hiring or spending decisions were made behind closed doors by school leaders or the volunteer boards that oversee the organizations.

David Renz, director of the Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership, said the number of potential conflicts WBUR discovered was “striking.”

“Even perceived conflicts of interest that are not a problem are — in fact — a problem from a credibility, trust and constituent relationships perspective,” said Renz.

WBUR reached out to dozens of school executives and board members, but few responded to requests for information. The analysis of taxpayer-funded special education schools is based on 10,000 pages of IRS tax forms, accounting audits, real estate records, lawsuits and other public documents covering a four-year period.

The findings also pointed to a lack of state oversight of the schools’ spending. The state’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) said it rarely scrutinizes the schools’ finances. This allows problems to fester at places like Broccoli Hall.

Massachusetts, like other states and the federal government, generally prohibits nepotism in the public sector, including school districts, and requires competitive bidding for big contracts.

Nonprofit schools aren’t bound by those restrictions but must follow federal and state laws that require deals be reasonable and meet fair market standards when they involve leaders or board members.

Unlike most private schools — such as college preparatory academies — special ed schools’ curriculums are overseen and approved by DESE every three years. They teach students with behavioral issues and learning disabilities, such as autism and dyslexia.

Under federal law, children whose needs can’t be met at their public schools can attend the special ed schools — with local school districts footing the bill. Tuition ranges from $60,000 to $500,000, depending on the program. Some are day schools with small class sizes; others are full-time residential programs. Many parents say they’re vital, with some families battling local districts to pay for their children's spots.

The price tag for taxpayers is steep — and rising. Last year, Massachusetts spent $804 million on tuition payments and transportation costs. More than 7,000 students attend the schools each year.

Special education schools cropped up out of necessity decades ago. Until the 1970s, public schools had few resources to help students with special needs. Some parents started private schools from scratch, out of their homes or rented buildings.

Many of the schools eventually became part of the state’s network of special education programs. And in some of them, the concentration of power still lies with family members who founded the organizations.

Financial mismanagement and family hires

Jane Jakuc has held the reins at Broccoli Hall since its founding more than 25 years ago. Before that, Jakuc led another special education school in Sudbury called Willow Hill. She employed her husband, Dan O’Hara, as a teacher and janitor.

In June of 1997, after expressing concerns about finances at the school and the couple’s combined salary, the Willow Hill’s governing board voted against renewing her contract, effectively ousting her. (Jakuc disagreed with the board, according to court documents.)

But by then, Jakuc had already petitioned the state to open a new special ed school. With the state’s approval, Jakuc opened Broccoli Hall’s doors to students the next year, serving as both head of school and board president. Again she hired her husband.

By 2008, she had hired their son too. Jake Egan, who isn’t a licensed teacher, directs an annual school theater performance.

Hints of financial problems at Broccoli Hall started emerging in 2011. As required by the state each year, the school hired an accounting firm, Smith, Sullivan & Brown, to review its finances.

In its audit, the firm discovered the school had undocumented spending and poor financial controls. The accountant stated the school relied too much on a credit card for purchases, charging nearly $130,000 that year.

“Many of the receipts for the credit card purchases were unavailable for inspection,” the report stated.

The firm submitted a plan to the state, and Jakuc and the school’s governing board pledged to correct course“immediately.”

While some of the financial problems were resolved, others cropped up or never fully went away.

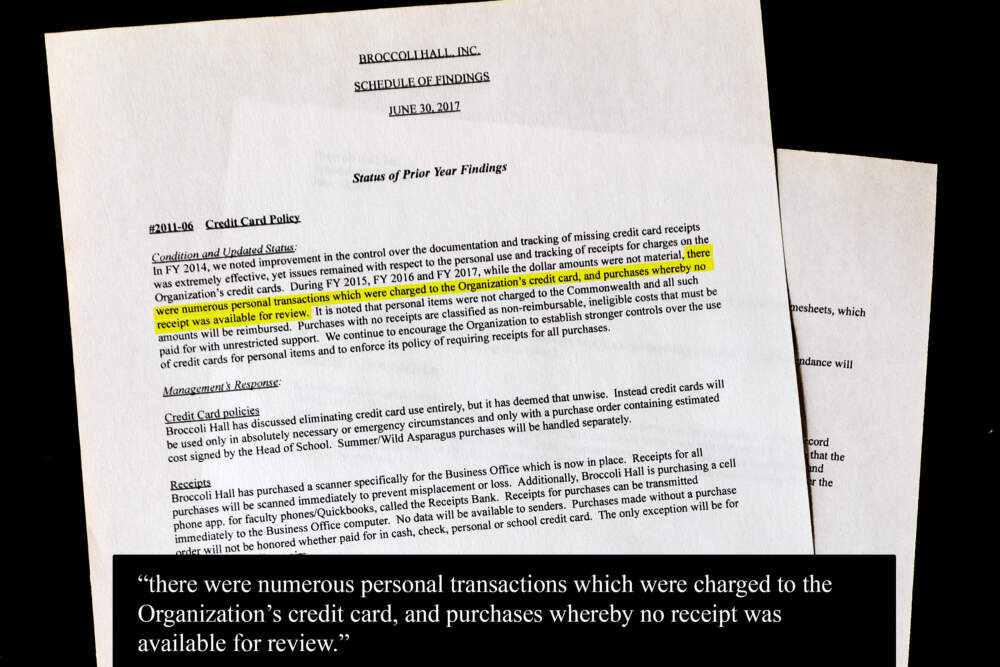

The accounting firm repeatedly found “numerous personal transactions” were charged to the school’s credit card up until 2017, sometimes with missing receipts. It didn’t name who was responsible, but stated such charges should stop.

Other records, however, did reveal the family was behind some of the spending. Broccoli Hall’s 2014 federal tax filing showed Jakuc charged $2,485 in personal expenses to the school’s credit card. The following year, Jakuc’s son charged $664 to the card. Both transactions were approved by the board as loans. The mother and son later paid the school back.

Jake Egan is in charge of the winter musical. Students must participate to graduate and classes shut down for all of January for the production.A 2019 review of the school by DESE found it met state requirements for academics, safety and health.

Egan made $102,000 in 2021, the third-highest paid staffer at Broccoli Hall. His father, Dan O’Hara, earned $121,000 and his mother, as head of school, earned $144,000. All declined to comment for the story, as did the school’s board members.

A former science teacher at Broccoli Hall alleges she was fired in 2021 after confronting Jakuc’s son about decisions including “over the top pricey” purchases for the school musical.

“I got called in front of Jane [Jakuc]. It was scary because who wants to be yelled at and fired,” Pamela Clapp said.

“It took a while for it to dawn on me … how much of a family business it really was,” added Clapp, who now teaches at a school in Newton.

That year, the accounting firm’s audit of Broccoli Hall found Jakuc had inappropriately approved timesheets submitted by a family member, and that “minimal detail was provided on the work performed” by the unnamed relative.

"It took a while for it to dawn on me … how much of a family business it really was."

Pamela Clapp

Nepotism can make it difficult for organizations to discipline employees who are also relatives of one another, said Cynthia Rowland, a San Francisco tax attorney who specializes in nonprofit law.

“It's absolutely a best practice to have family members not reporting to family members,” said Rowland.

Jakuc pledged to stop signing off on her husband and son’s timesheets, the report states.

But the most recent audit of the school — filed in February — showed Jakuc continued the practice: “We found a lack of appropriate supervisory authorization” for two years.

The school also failed to have written agreements for some of its outside contractors, the audit found.

It’s unclear if Broccoli Hall’s 11 board members worried about the spending problems or appearance of nepotism. Each year, members reviewed the audit and approved a plan to fix the issues, including Jakuc as board president.

WBUR reached out to board secretary Mark Bombara, but he declined to comment or provide meeting minutes.

The role — and conflicts —of governing boards

While public schools rely on elected committees to approve budgets and evaluate school leaders, private special ed schools like Broccoli Hall are overseen by governing boards.

The boards are made up of volunteer members appointed by the school who hire and set pay for top executives and approve school budgets. Members are advised to avoid doing business with nonprofits they oversee.

The Massachusetts Office of the Attorney General, which helps regulate public charities in the state, urged nonprofit boards in 2022 to be “very cautious” about these transactions, in part because they “may look questionable to the public.”

But WBUR’s investigation found financial conflicts were common between the schools and their boards. More than half of the 76 organizations disclosed at least one transaction from 2019 to 2023 involving a board member or their relative.

The analysis revealed contracts for lawyers, insurance agents and financial managers. One board member owned a company that provided medical prescriptions to a school. Another was on the board of a business that supplied food to the school. Several others were paid consulting fees.

In the case of Broccoli Hall, records show the school on four occasions hired board members or relatives for jobs. In 2022, Broccoli Hall paid two unnamed board members a combined $30,000 and the relative of a board member about $15,000 for consulting work, according to state records.

Laurie Styron of CharityWatch said these types of transactions can indicate that governing boards may not be providing adequate oversight.

“If the organization had completely independently functioning boards of directors, would those boards have determined in all of these cases that family members of other board members or executives were the absolute best people for the job?” she asked.

Styron said board members should collect bids from multiple vendors and any interested or affected parties shouldn’t vote. Organizations should take board minutes that reflect its decisions are in the nonprofit's best interest.

The nonprofit schools state they have conflict-of-interest policies as required by the IRS. Broccoli Hall, for example, has a policy requiring school leaders and board members to “leave the room” if there’s discussion or vote on a potential conflict.

But it’s unclear how the schools’ governing boards make their decisions. Board minutes and meetings, for example, aren’t public.

In another example, Broccoli Hall employed Mark Dutkewych, the husband of then-board member Lisa Freedman, starting in the 2014 fiscal year. He and his wife left Broccoli Hall in 2019. They declined to comment.

Tax-exempt organizations like Broccoli Hall should also disclose potential conflicts of interest like these to the IRS and the public, Styron and other experts said. If transactions aren’t divulged, a nonprofit could face IRS penalties including fines.

For two of the years that Dutkeywch worked for the school, it didn’t tell the IRS. In 2022, the school also didn’t reveal to the IRS that Jakuc' two relatives - her husband and son - worked there.

Defenders of the private schools say there are safeguards in place.

Elizabeth Becker, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of Approved Private Schools, said in a statement the schools hold themselves “to the highest levels of professional standards” when reporting to their governing boards and state regulatory officials.

“Our member schools have layers of checks and balances including annual audits to uphold the expectations of excellence,” said Becker, whose group lobbies on behalf of special education schools.

But WBUR’s investigation found these fiscal audits aren’t routinely inspected by the state.

Fragmented state oversight

Decades ago, the state auditor’s office investigated private special ed schools and ordered some of them to return millions of dollars in misspent funds. But in recent years, the office hasn’t audited the schools and is not mandated to do so.

The only organization that minimally reviews some of the schools’ finances is a little known agency called Operational Services Division or OSD.

It’s the state’s procurement agency, which requires state contractors — including the schools — hire an accounting firm and produce an audited financial report every year.

But the details of those financial audits weren’t being reviewed by OSD, according to a highly critical 2018 report from the state auditor’s office. This might have cost Massachusetts tens of millions in inappropriate spending, the office stated.

The audits are designed to alert the state of financial problems and require corrective action plans. For 13 years in a row, Broccoli Hall and Jakuc were put on notice to take “immediate” steps to fix its lapses.

But it's unclear if state officials paid any attention.

In a statement, OSD said the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is supposed to examine — and enforce — such plans. But DESE spokesperson Jacqueline Reis said the responsibility lies with OSD if there’s inappropriate spending.

“Routinely inspecting the … audits has not been a focus of our work in the past,” Reis said.

When asked if the department has penalized schools for mismanaging public funds, she didn’t answer.

In response to WBUR’s questions, Reis said DESE would change its policy to develop “a more structured process for timely review and follow-up for financial corrective action plans” – though the timeline is unclear.

In October, the U.S. Department of Education launched a probe of DESE’s supervision of special education, including the private schools. Complaints by parents and educators spurred the inquiry.

Among those calling for reforms is education advocate Ben Tobin, who helps parents navigate the private special ed system. He said the public currently has no way to know how taxpayer money is being spent at these schools.

“If they're taking the same funds as a public school, they should be held to the same standards," said Tobin, who supports legislation for more state control over these schools.

A key state lawmaker said the prevalence of conflicts discovered by WBUR in the schools warrants further scrutiny.

“I do think the vast majority of the schools are doing an excellent job — but we need to do everything to make sure that's the case,” said state Sen. Jason Lewis, who co-chairs the Legislature’s education committee.

For several years, bills that would require private special education schools to report financial information, including conflicts of interest, to DESE and the auditor’s office have stalled.

Tobin hopes similar legislation now in committee faces better odds, especially in light of the federal government’s scrutiny of the schools.

He added, “If you're taking the money to work with kids with disabilities, it shouldn't be a lot to ask to have some transparency.”

With reporting from WBUR's Christine Willmsen.