Advertisement

The Murder That Forced A Divided Boston To Reflect

That night 20 years ago is one that I will never forget. I had been out in a ride-along with two Boston Police detectives as they enforced the department's new "Stop and Frisk" policy. Gang violence was rampant in some Boston neighborhoods — so widespread the BPD had created this program to assuage community fears.

People were on edge after a woman, sitting in a chair in her own home, narrowly missed being shot. Police were authorized to "stop and frisk" suspected gang members. By many accounts, officers had gone overboard, randomly stopping young black men without cause.

Police were under fire for violating basic civil liberties of young men who were not gang-bangers and had been stopped for no apparent reason, other than that they were black and walking along a street in a high-crime neighborhood.

I was working on a report about "Stop and Frisk." After spending a couple of hours with the detectives, I went to a meeting of citizens concerned about gun violence. They were speaking out in support of the BPD.

That night when I got home, my husband said to me, "They've shot a pregnant woman." On Oct. 23, 1989, the story was all over the nightly news, because the television show "Rescue 911" had been riding along with a Boston emergency response crew that night and had been with the ambulance that responded to the Stuart shooting.

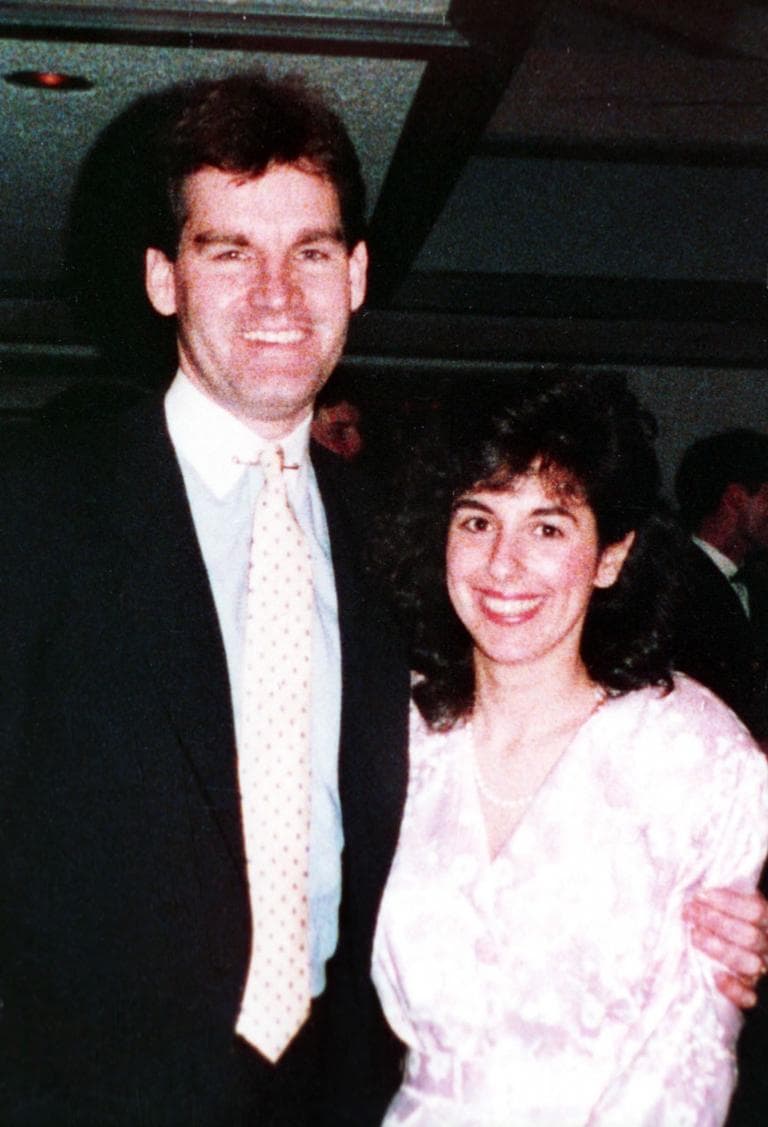

The images were gripping. Carol DiMaiti Stuart slumped over in the front seat of her car, her husband in the driver's seat. Charles Stuart had been shot in his torso. His wife had been shot in the head.

He told police he had been shot by a black man with a raspy voice, wearing a black jogging suit with red stripes (a popular look that year). Charles Stuart said he and his wife had just left a childbirth class at a nearby hospital when the man jumped into his car on Huntington Avenue and demanded money.

The story did not ring true to me. Why would a man shoot a woman who was eight months pregnant in the head and shoot her husband in his side? She was no threat.

At that time of night, Huntington Avenue was a fairly busy street — why had no one seen this man with a gun forcing his way into the car? Later, when police released 911 tapes of Stuart calling in the shooting, he's asked his location. Stuart says "I'm at Tre...." and then stops (pretending, to me, to be disoriented). He was indeed near Tremont Street in the Mission Hill area of Boston. When asked about his wife, he volunteered that he had "ducked" — an apparent explanation for why she was shot in the head and he was not.

Charles Stuart's story had big holes in it, I thought. My husband did not agree. We debated this. He said if drugs were involved, anything is possible.

The next morning it was all anyone was talking about. A photo of Carol Stuart apparently near death in her car was splashed across the front pages of a daily newspaper. I was in a taxicab when the driver started talking about it. "The husband did it," he said. Charles Stuart had said the man demanded $100 cash.

The cab driver said druggies don't go after suburban couples; they don't carry cash, only plastic. If the thief wanted cash, he'd rob a cab.

"The story did not ring true to me. Why would a man shoot a woman who was eight months pregnant in the head and shoot her husband in his side?"News reports focused on the tragedy from the angle of a young, white, suburban couple, coming into Boston for childbirth classes as they prepared for the arrival of their first born child. They were dubbed the "Camelot Couple." Carol was an attorney. Charles worked for a prominent furrier.

Boston Mayor Ray Flynn was on television vowing to "get the animals responsible" for the shooting. Police stepped up their "Stop and Frisk" program. Mothers in the Mission Hill neighborhood complained of their sons being targeted, stopped on the street and forced to drop their pants as police searched for a suspect.

News accounts did not question Stuart's report. But there were questions in newsrooms and among police. One reporter told me of how she mentioned that the people in her hair salon were speculating that the husband did it. When she brought that information up in her newsroom, she felt her statements were dismissed as irrelevant.

Another reporter finally asked police, during a news briefing, whether Stuart himself could be responsible for the shooting. A police spokesman said no one had been ruled out, including the husband.

That news was drowned out by a report that Charles Stuart had picked Willie Bennett out of a police line-up. Bennett had earlier been involved in an attempted shooting of a police officer. Some say that made him a target for police. Then came the calls for the death penalty.

Many still wonder what might have happened if Charles Stuart's younger brother, Matthew, had not come forward to say that Charles was the shooter. Matthew says he arrived after the shooting and Charles gave him the gun used in the shooting and Carol's jewelry to get rid of, in a scheme to collect on a huge life insurance policy that Charles had taken out on Carol.

As police were closing in on Charles as a suspect, police say he committed suicide by jumping off a bridge into the Mystic River.

The case highlighted the racial divide in the city and led to introspection on a number of angles, including by the media. While people — black and white — questioned the story, news managers, in the introspection that followed, admitted they believed Charles Stuart's story, that it rang true to them.

What if they had listened to all voices in the newsroom?

Delores Handy hosts WBUR's "All Things Considered." She was recently inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame.

This program aired on October 23, 2009. The audio for this program is not available.