Advertisement

Evidence Of Misconduct: A Prosecutor, A Mobster, A Witness Who Lied

Resume

When Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Auerhahn joined Boston’s war on organized crime, he turned his focus to an up-and-coming mobster named Vincent Ferrara. The operation was called “Tunnel Vision," which would prove a fitting description for Auerhahn's alleged rule breaking to bring down his target. Auerhahn thought he had a smoking gun in a witness who testified that Ferrara ordered a hit. Problem is, the witness lied. Worse, a judge ruled Auerhahn knew he lied — and covered it up.

The case raises troubling questions from critics who worry that withholding evidence has become a tactic of some federal prosecutors. Those critics question whether Justice can police itself. In this first report of a three-part series, we consider the crucial evidence that Auerhahn never turned over.

We must never forget the Supreme Court's direction that a criminal trial is the search for the truth.

U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan

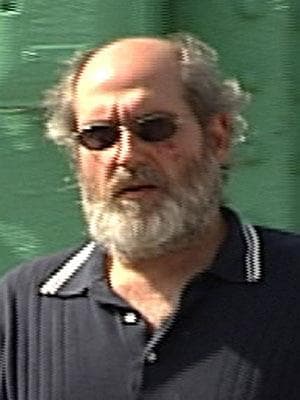

Attorney Bernard Grossberg looks out on Boston Harbor and remembers what a lecturer once said in law school: "An ethical, competent prosecutor is worth a thousand defense lawyers. And if a prosecutor has all that power and is unethical, it just destroys the justice system."

Grossberg is talking about the problem of misconduct and what he and some other attorneys and even some judges call the growing penchant by federal prosecutors across the country to withhold evidence from defendants.

Here in Boston, Grossberg is thinking about Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Auerhahn, who has become the local face of that problem for the Justice Department. Grossberg knows the case well; he represented one of two defendants who a federal judge found were deprived of their rights to a fair trial because of Auerhahn's misconduct.

Grossberg still expresses amazement at what the court hearings uncovered. "You never, ever, ever expect a prosecutor — a fellow attorney — to do what Auerhahn is accused of doing," he says.

You can make no more serious accusation against a federal prosecutor than that he withheld evidence of a defendant’s possible innocence. To do it when the charges involve murder is even worse. Yet both a federal judge and the federal Court of Appeals, in upholding the judge, found that Auerhahn, the career prosecutor, did just that.

They’ve called his behavior “outrageous," “egregious," "feckless" and “painting a grim picture of blatant misconduct." Yet seven years later, Auerhahn remains on the job as a federal prosecutor here in Boston. He’s never been publicly reprimanded or disciplined by the U.S. Department of Justice.

One of several judges who now question whether the Department of Justice is capable of policing itself sits in Boston. Mark Wolf is the chief judge of the federal Court of Massachusetts. Unsatisfied by the response of the Justice Department to the allegations against Auerhahn, Wolf has triggered local disciplinary proceedings.

The assistant U.S. attorney could face potential suspension or disbarment by local authorities.

'The Animal' Is Caged

The roots of Jeffrey Auerhahn's current problems reach to the 1980s, when he joined the U.S. attorney’s office and the war on organized crime, which, in Boston, meant the war against the Mafia. One of his targets was Vincent Ferrara, who was a "Capo" — a captain in the local Mafia — and an up-and-comer.

I am what I am. I did what I did.

Vincent Ferrara

Auerhahn and the Organized Crime Strike Force considered Ferrara a very dangerous man. They dubbed him “Vinnie the Animal." And they caged him in 1989, after the FBI bugged a Mafia induction ceremony.

Paraded into court with a mob of Mafia soldiers attached arm and arm to federal agents, Ferrara was indicted for racketeering and related charges of extortion, gambling and murder.

You never, ever, ever expect a prosecutor — a fellow attorney — to do what Auerhahn is accused of.

Defense Attorney Bernard Grossberg

Over a recent cup of coffee, Ferrara reflects: "I am what I am. I did what I did."

With a degree of candor that's disarming, Ferrara says, "there was so much evidence against me for lesser crimes" that he was inclined to reach a plea deal with the prosecutor in order to serve less time. But the murder charge was a killer.

Auerhahn had a cooperating witness willing to testify about Ferrara's involvement in a murder. The witness’s name is Walter Jordan. In 1985, Jordan had accompanied his brother-in-law, a mob wannabe named Patsy Barone, when Barone robbed and murdered another mob wannabe.

The crux of Auerhahn's case, says Barone's lawyer, Bernard Grossberg, is this: "Walter Jordan testified that Vinnie Ferrara told Barone to kill the two guys who were eventually killed."

It is that one sentence from Auerhahn's witness — that Ferrara ordered the murder, that one sentence — upon which the prosecutor's entire case for the charges of murder and conspiracy to murder rests.

Ferrara — who readily admits he is what he is and he did what he did — insists that was something he didn't do.

"Let's cut to the chase," I say to him, thinking that in his new state of candor, Ferrara might tell if he did. "Did you order the murders of the two men?"

"Absolutely not," he replies. "They knew firsthand that I was innocent of it."

Innocent, Ferrara claims, but based on Jordan’s testimony — or at least his official testimony — Ferrara pleaded guilty to that one murder in 1992. He got a longer sentence, but if he had maintained his innocence, gone to trial and gotten convicted, he could have gone away for life. Ferrara got 22 years. And Barone, who was found guilty of murder conspiracy in 1993, got life.

Few people shed any tears that a Mafia captain and a violent thug were going into the hole. Auerhahn and the Organized Crime Strike Force were winning the war.

The Sole Witness Admits: 'I Lied'

A decade went by. Then in 2002, Grossberg got a chilling call from the past, "completely out of the blue," he says.

On the other end of the telephone line, from somewhere in hiding, was Walter Jordan, Auerhahn’s chief witness 10 years earlier. A troubled man with a number of motives, he had something he needed to say. Remember how he's testified that Ferrara ordered the murders? It wasn’t true.

"He says, 'I lied,' " Grossberg recalls. "And that he lied at the behest of various government agents in the case."

Floored by what he'd heard, Grossberg filed a motion for a new trial. Judge Mark Wolf, who had presided at the original trial, called for hearings. They occurred in September 2003.

Back came Jordan, Auerhahn's witness. A con man, a suspected accomplice to murder and a liar either then or now, Jordan might have had little credibility the second time around as a witness. But then came a bombshell from a retired Boston police detective who had worked alongside Auerhahn on the Organized Crime Strike Force.

The detective’s name was Martin Coleman. "And Marty Coleman testifies at this hearing that in no uncertain terms Walter Jordan recanted," Grossberg says.

According to the detective, Jordan had confessed to him in private late one night in 1991, just as Jordan claimed. Jordan had confided to Detective Coleman that Ferrara, the mob Capo, had not ordered the murders.

The truth, Jordan told the detective, was that his brother-in-law, Barone, had acted on his own. Detective Coleman testified that he was shocked. Auerhahn and the prosecution team were preparing to argue in court that Ferrara had ordered the murders in order to climb another step up in the Mafia.

Coleman knew that the witness’s change of story completely undercut not just the prosecution’s theory, but its whole murder case. Yet Coleman also knew what he had to do, he says. He had to tell the prosecutor because exculpatory evidence "has to be turned over to the defense.”

Coleman testified that he told Auerhahn that his witness, Jordan, had recanted. When Auerhahn got this news in 1991, he could not have been happy. Jordan was Auerhahn's only witness, the only one who could say "Vinnie Ferrara ordered the murder." Now Auerhahn’s witness was going wobbly on him.

At the end of July 1991, a few days after Jordan recanted to the detective, he recanted a second time, now to the prosecutor and the detective together, Coleman told the court. But Auerhahn never disclosed Jordan's change of story to the defendants' attorneys, in either 1991 or the years that followed.

Instead, Jordan later claimed, Auerhahn scared him back into sticking with his original story. Auerhahn’s FBI agent added physical threats to keep him in line, Jordan claimed. “They made me lie," he said. So, Jordan said, he went back to the testimony that damned Ferrara and convicted Barone in 1993.

The Missing File Is Found

Fast forward to the court hearings in 2003. Grossberg and Ferrara's attorneys are in Wolf's court room trying to get new trials for their defendants based on Jordan's claim he lied. "I never expected there to be a written report confirming what Coleman said," Grossberg says.

At first, the hearings seemed to be a matter of Auerhahn's word against Jordan's and Detective Coleman's. But then defense attorney Bernard Grossberg asked Coleman something to the effect of, "Wouldn't you as a detective be required to write down what you heard?"

"And to my great, great, great surprise," Grossberg remembers, "Coleman said, 'I did.' I was flabbergasted. Everyone else just sat up. And I said, 'Where's the report?' And he said, 'I gave it to Auerhahn. The report's in the file.'"

Stunned by the answer, Judge Wolf called a recess. He ordered the feds to find the file. Sure enough they found it. And in the file was Coleman's handwritten memo from 1991, just as he has said. And Coleman's report said exactly what Coleman testified he told Auerhahn: that Walter Jordan had recanted.

Judge Wolf called it “the smokingest gun I’ve ever seen."

What was in that file? And what does that say about Auerhahn? Find out in the second report.

This program aired on February 17, 2010.