Advertisement

The Case Of The Baseball Painting Mystery

It was a cold winter day. I was in my office, feet on my desk, scotch in my hand, hoping another case would come along — that’s when she walked through my door...

OK, it was a little less dramatic than that.

One morning in February, I got to work, sat down in front my computer, opened an e-mail, skimmed the text and clicked on the attachment. An image appeared — two boys probably between the ages of 10- and 13-years-old. One boy has dark skin, one light. They’re both holding bats and one boy is holding a ball. Just an ordinary sports scene, except the boys are wearing long frocks and white dress shirts with broad, frilly collars and the image is a black and white copy of an oil painting done more than 200 years ago.

Mario Valdes is the man who sent the e-mail and he’s been thinking about that image off and on for the past 35 years. Valdes is a freelance researcher based in Boston who focuses primarily on genealogy and African-American history projects. He first saw the double portrait in an issue of the art magazine, Apollo.

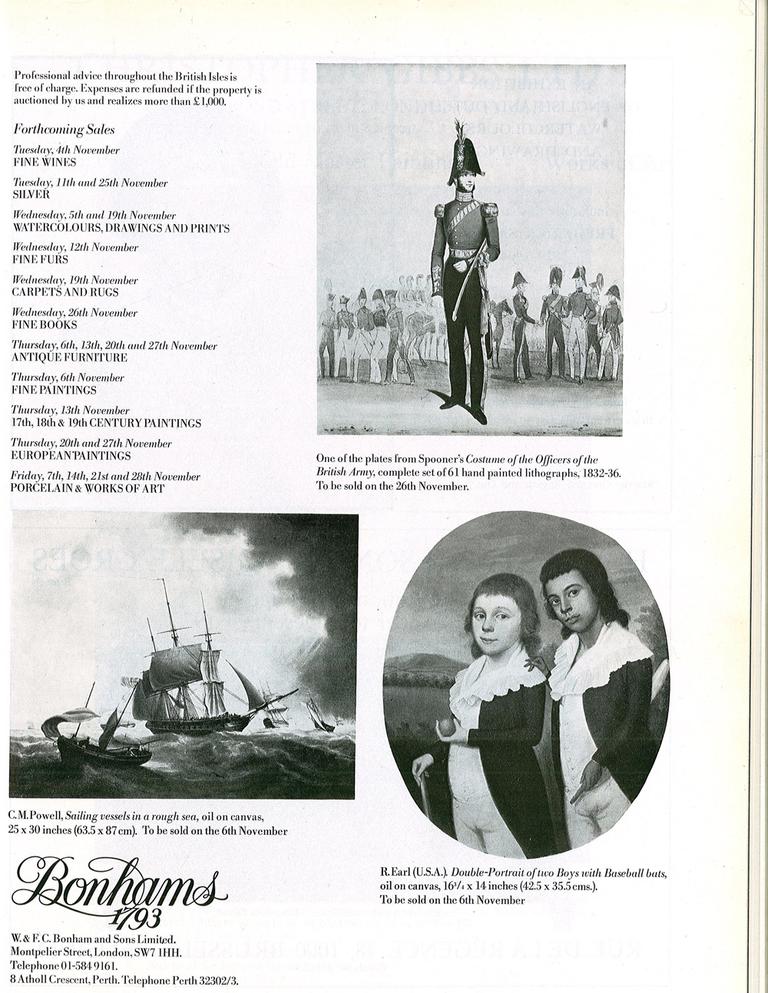

“Back in 1975, I stumbled on an advertisement by Bonhams for the sale of this painting, described as a piece by Ralph Earl,” Valdes said. “I was quite intrigued by it because one of the kids was black or Indian, I couldn’t tell. But, of course, that’s what caught my attention.”

The magazine ad lists the title as "Double-Portrait of two Boys with Baseball bats," but Valdes saw the painting as an unusual black history item. Over the years, he did some digging in his spare time, but it was three decades before Valdes realized the painting’s potential significance in the world of sports.

In 2004, research by historian John Thorn led to the discovery of a 1791 Pittsfield bylaw containing the earliest written reference to baseball in North America. Valdes says when he heard the news, the portrait immediately came to mind.

“That’s when I thought, ‘My God. Everyone’s going ballistic over just this one little description, this one little mention of a baseball,’” Valdes said. “And I’m sitting on what claims to be the earliest painting of baseball, if it indeed is baseball.”

Advertisement

Valdes picked up his research again, starting with a call to Bonhams, the London auction house where the painting was sold, but the company had destroyed its records from that time. Valdes didn’t give up. He spoke to baseball and cricket historians, contacted art experts and even learned the boys’ frilly collars most likely date the painting to the late 1700s. But while tidbits of information piled up, the painting’s location was still a mystery.

So when Valdes contacted me to see if I wanted to try to solve the case for a radio story, I began by talking with him at length. Then I started down some of the same roads he’d already followed and also went down several new ones.

In April, I made a trip to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., to talk with Senior Curator Tom Shieber. Shieber says there aren’t many objects children in an 18th-century portrait could be holding that would really grab our attention in 2010.

“What I think is so neat about this is that we’re interested in it," Shieber said. "That’s what’s neat about it because it tells you that baseball means something to people. Even to those who are not particularly interested in the sport. It’s in our language. It’s in the clothes we wear. It’s in the advertising that’s bombarded into your head every day. It’s everywhere you look. You talk about rose-colored glasses, we’re wearing baseball-colored glasses here and so we’re seeing baseball in this image.”

It was reassuring that Shieber shared my enthusiasm, but his assessment of what the painting might tell us was less optimistic.

“This particular painting, there’s not a lot to grab on to," Shieber said. "We don’t have a good look at the objects that interest us: the ball and the bats. It’s possible that ball has some stitching on it that might lend a clue. I just can’t tell from this image. There’s a background that’s not helping me out right now and maybe we could try and figure out where it is. I’m not even sure if we did how much that would help. So, there’s not a lot to go on here.”

The best available clues are in the 1975 magazine ad, which lists Ralph Earl as the artist. Earl was a prolific portrait painter who was born in Massachusetts in 1751 and worked throughout the Northeast. He died in 1801. So at least that confirms it’s an American painting, right? Not so fast.

Earl was born in the American Colonies, but was loyal to the crown. He fled to England in 1777 during the Revolution and didn’t return until 1785.

Beth Hise is a museum curator who organized an exhibit titled “Swinging Away: How Cricket and Baseball Connect,” which is showing in London and coming to the Baseball Hall of Fame next year. Hise says 18th- and 19th-century English portraits of people holding cricket gear are relatively common. But what if there was proof Earl was painting American boys?

“Then the kind of equipment that they’re holding would be the first clues that we would have of what bat and ball equipment looked like in the colonial American context or the post-colonial American context,” said Hise, who lives in Sydney, Australia. “Then this would be an extraordinarily significant painting. But if we don’t know that, then it becomes an interesting painting that’s potentially part of an English tradition.”

In the painting, the boys are dressed identically in upper-class fashion. There’s also a sense of closeness, with the dark-skinned boy resting his hand on the other’s shoulder — a pose that often suggests the subjects are family members. Mario Valdes’ genealogical research eventually led him to theorize the boys were members of the Rogers family, a prominent Connecticut clan that had some interracial marriages.

"Since Earl is painting in Connecticut, in the Connecticut area that’s primarily his home base, this stands a good chance to be them,” Valdes said.

But — in a development I’m beginning to get used to — there’s another complication: Despite the description in the 1975 ad, it’s not certain that Ralph Earl was in fact the artist.

After calls to the Smithsonian and other museums, I eventually found a curator who’s an expert on Earl. Betsy Kornhauser of the Metropolitan Museum of Art was with the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn. when we spoke this spring. She told me without seeing the actual painting she couldn’t be certain it was Earl’s work and added that a number of portraits have been mistakenly credited to him.

So, I was back to staring at the ball and bats. Here’s one fact I can confirm: Studying an image for clues is tricky business. When you see something incomplete, like a word missing letters, your mind automatically tries to fills in blanks. One boy is leaning on a bat, but we only see the handle. The other is holding his bat under his arm. We see both ends, but not the middle.

I needed help and I turned to David Block, the author of “Baseball Before We Knew It” and an expert on early bat and ball games that contributed to the evolution of baseball. Block says the ball could have been used in a number of games, but the two bats are even tougher to pin down and might even be different types.

“The longer one appears to have a knob on the end that the fellow’s resting his hand on, while the one on the right is a one-handed bat, fairly thin,” Block said. “And if I were to speculate as to what that bat most likely would be used for from that era, I would say the game of trap ball.”

But what about the title, "Double-Portrait of two Boys with Baseball bats"? Nearly all of the historians I spoke with agree it is most likely a description written by the auctioneers. Unlike the ad, the earliest American references to “baseball” are almost always written as “base ball” and a different game by the same name in England was written as two words or as “base-ball.”

In other words, it’s another dead end. Over the past nine months I’ve hit a lot of them and come up empty.

It’s been fun, and frustrating. But I take comfort in the words of Baseball Hall of Fame's Tom Shieber, who has done a lot more of this kind of work than I ever will.

“To me it’s about the means, it’s not necessarily about the end," Shieber said. "The research process to me is the most fun. If I can get something neat at the end, great. It can’t just be about the end, because a lot of times I don’t get there.”

So, I’m throwing in my amateur historian towel and hanging up my research cleats. Until someone finds the actual painting, we might never know the full story of the boys and the game they played. And it’s time to move on. Unless I can get just one more clue…

This story originally aired on WBUR's Only A Game.

This program aired on October 23, 2010.