Advertisement

Treasured Velazquez Restored And Re-Hung At The Gardner

[/gallery]

BOSTON — The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum welcomes back an old friend this week — a treasured portrait by 17th century Spanish master Deigo Velazquez that's been off-view to the public while undergoing a major restoration.

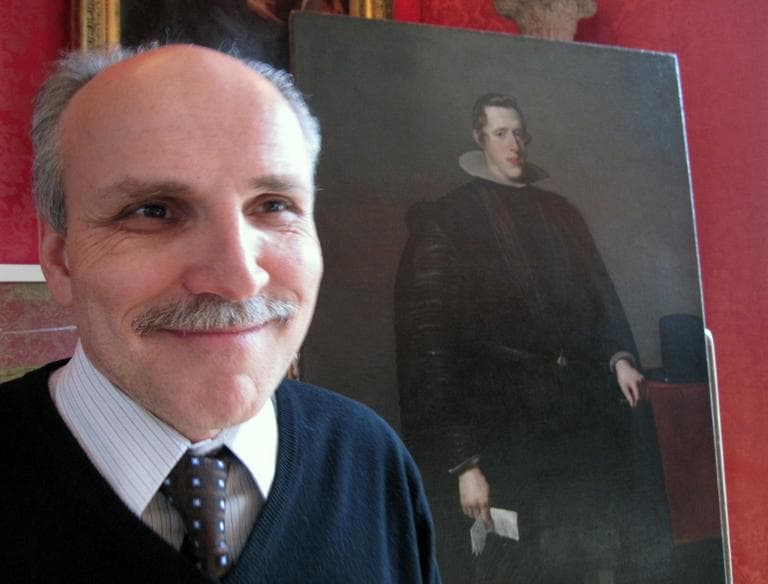

The work depicting Spain's King Philip IV is reclaiming its former spot in the Gardner's Titian room. That's where I met with Gianfranco Pocobene, head of conservation at the museum. He's labored for hundreds of hours to give the nearly seven-foot tall portrait, dated 1628, it's painstaking face-lift. On Tuesday it stood before us, refreshed and upright at floor level, waiting to be re-hung in it's gilded frame.

Before we talked about the restoration process, Pocobene reminded me of the work's origin and significance.

"What's fascinating about the painting and the history is Velazquez arrives in Madrid in the early 1620s, and he's appointed the sole court painter for the king," he said. In that role the young artist executed an ongoing series of related pieces featuring the king in a variety of poses.

He did this for decades. Velazquez and his workshop also made official copies of the monarch's image for ministers and courtiers in Spain. The Gardner's painting is an exact replica of the famous portrait in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

There are about 110 known paintings credited to Velazquez and his workshop. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has a King Philip portrait in its collection. Just last month the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York re-attributed its restored painting to the artist, which made headlines (In 1973 the Met determined it was likely not by Velazquez, although many long questioned that conclusion — apparently with good reason).

As for the Gardner's King Phillip, Pocobene said it was indeed painted by the artist and his followers. Bringing their centuries-old portrait back to life has been an honor for him, but he admitted it was also a challenge.

It was last restored by museum conservators in 1948. Over the years the varnishes used back then had darkened and gone murky, Pocobene recalled. Combined with accumulated surface grime they created "sort of a veil over the surface of the painting," he said.

But his modern conservation treatment yielded dramatic improvements in the painting's appearance. In essence Pocobene was able to re-saturate the image during the process. Now the young monarch pops out of its grayish, almost other-worldly background.

In the portrait King Philip strikes a regal pose. He's dressed in deep black. A simple white collar frames his fleshy young face. The cleaned-up composition emphasizes the tension in the portrait, according to Pocobene.

"I think with the removal of the old varnish and restorations you get this sort of contrast of the hands and face rendered in this very realistic manner," he said, pointing to the fingers, "and that's one of the things Velazquez is really noted for, is this realism that he was able to portray in his pictures. There's this kind of interesting dynamic between the realism of the figure and this abstraction of the background."

Up close the painting looks refreshed. Gleaming. You can see the pink in King Philip's cheeks and the folds in his dark garments.

Pocobene said he also learned much more about what went into making this great work. He had the opportunity to conduct a thorough technical analysis of the portrait, thanks to the Gardner's current building expansion.

The museum's new building will be completed in early 2012, but right now Pocobene's old facilities are disassembled as his new space is being constructed.

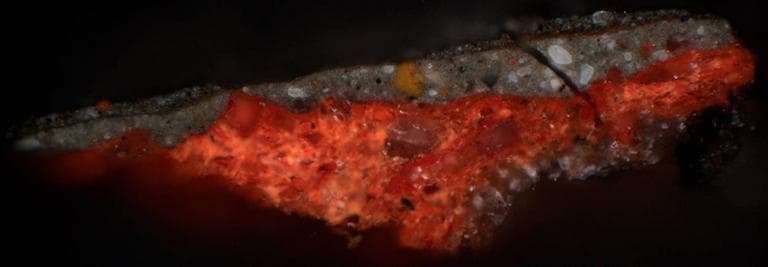

To do his work on the Velazquez, Pocobene rented conservation labs across the river at the Harvard Art Museums. There Pocobene had access to x-radiography, infrared imaging, UV examination and cross-sectional analysis, "which is where we take small paint samples and analyze the characteristics of the paint," he explained, assuring me that the samples were tiny, "smaller than a grain of sand."

He showed me a photo of a cross-section of a speck of paint. Two distinct layers of paint were clearly visible, but also the remnants of previous restorations. This helped Pocobene plot his conservation strategies.

For him the most significant finding revealed the presence of a "red earth ground layer" which Velazquez and his assistants applied to the canvas before painting the portrait. The artist employed this technique only for a few years in the 1620s, according to Pocobene. Technically the discovery of this layer places the work firmly in that period, he said. The red layer also made a considerable impact on the resulting image, giving it a warmer tone. "So all of this technology is fascinating to inform you as you go along with the process of doing the work," he added.

In the end, Pocobene said it's been a thrill to spend so much quality, intimate time with Velazquez's portrait of King Philip IV. But he'll be glad to see it back on the wall in the Gardner's glorious Titian room, where it belongs. Works like this are rare treasures, the conservator mused with a humble smile, "and you don't get another chance if you don't do it right."