Advertisement

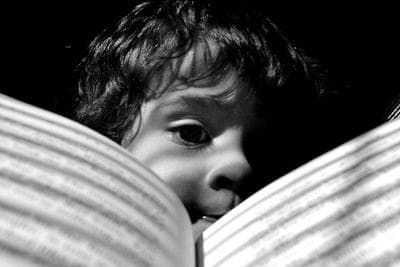

Making Sure Mass. 3rd Graders Are Strong Readers

Resume

When it comes to reading proficiency, third grade is a critical benchmark.

If students don't have strong reading skills by the time they finish third grade, they're more likely to lag behind academically in later years, according to a growing body of educational research. Yet 37 percent of Massachusetts third graders read below grade level, and that number jumps to 57 percent among children from low-income families.

So state lawmakers recently introduced legislation aimed at ensuring that all Massachusetts children are proficient readers by the end of third grade. The bill would establish an advisory council to review reading-related curricula, professional development and testing statewide.

To detail this effort, WBUR's All Things Considered host Sacha Pfeiffer recently spoke with Rick Weissbourd, a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Kennedy School of Government, a founder of city-wide literacy initiatives ReadBoston and WriteBoston, and a board member at the Boston nonprofit Strategies for Children.

Rick Weissbourd: There are kids who enter kindergarten in the Boston Public Schools — a small fraction — who don't know words like "knee" or "elbow," don't know the names of their body parts. And if that is happening, there is very little conversation going on. And that was shocking to me.

Sacha Pfeiffer: How does that happen? How does a kid get to that age and not know words that basic?

I think it's because kids are parked in front of the television. On average, it looks likes kids 2 to 4 years old are watching three to four hours of television a day and that doesn't include other kinds of screen time. It doesn't include video.

"... [R]eading should be a springboard for conversation. It should be a time to wonder out loud with your kids, to engage in conversation about lots of things in the world that come up in the course of reading."

But I would think that enough TV would eventually teach you words like "knee" and "elbow." Is there some benefit, in terms of vocabulary, to watching television?

It looks like television has very few benefits in terms of reading success. Kids can learn some slang from television. Sometimes they can learn a song from television. But in terms of really developing a rich vocabulary, television is not the way to do it. And I think it's better if parents are able to watch with their infants and toddlers and engage in conversation while they're watching TV. I mean, that can help build language, as well.

The "read to your kids" message, I think, is pretty well-circulated. But you're saying that talking to your kids is as important as reading to your kids?

Talking to your kids is absolutely as important as reading to your kids. It's a couple of different kinds of talk. Some parents think that they need to read to the kids for 20 minutes a day, and that's true. But they end up soldiering through the reading, they feel like they have to get through the reading, and reading should be a springboard for conversation. It should be a time to wonder out loud with your kids, to engage in conversation about lots of things in the world that come up in the course of reading. And it's also in just lots of conversation during the day — it's when you're cooking the meal or when you're taking out the garbage or when you're giving an infant a bath.

If a person is giving their child a bath, what's the ideal conversation?

One thing you might want to you might want to do is, on the way to the bath, if you have a 3- or 4-year-old, you might say, "Let's pretend to be an animal" on the way to the bath. You know, "Let's pretend to be an elephant," or a bear — whatever animal you want to be. And then you can talk about that animal and what that animal does, or make animal noises. Or, in the bath, you can sing a song with your infant and you can talk about the words in the song or you can tell a story. There are lots of opportunities for those kinds of conversations.

In lower-income households, in particular — because much of the research shows that reading proficiency is even lower among kids who grew up in low-income households — what is it that is not happening in those households, or that is happening in those households, that makes these kids so far behind in reading proficiency?

Part of this is working two or three jobs. Part of it is the stresses that low-income parents are under. Part of it is that when you're under stress you tend to be abbreviated in your conversation and you tend to use directives rather than to ask questions or really to engage in dialogue. So the quality of the conversation is abbreviated and different. There is a problem of depression in low-income communities, too. About 40 percent of parents, it looks like, in low-income communities are suffering from some kind of low-level depression — a really steady drizzle of helplessness and hopelessness.

This legislation would also try to make teachers better at teaching kids reading. But for kids who come in below the bar, who come in really behind the curve, how much can a teacher really do at that point?

A teacher can do quite a lot. I mean, it's not that kids are doomed if they enter kindergarten and they have low vocabularies. There's a lot you can do with kids in the early grades of elementary school. At high-quality elementary schools where kids get three really strong elementary teachers in a row, for example, you see big gains in the number of kids who are reading proficiently. And I think we have to recruit really strong teachers. We have to retain really strong teachers.

This program aired on February 14, 2011.