Advertisement

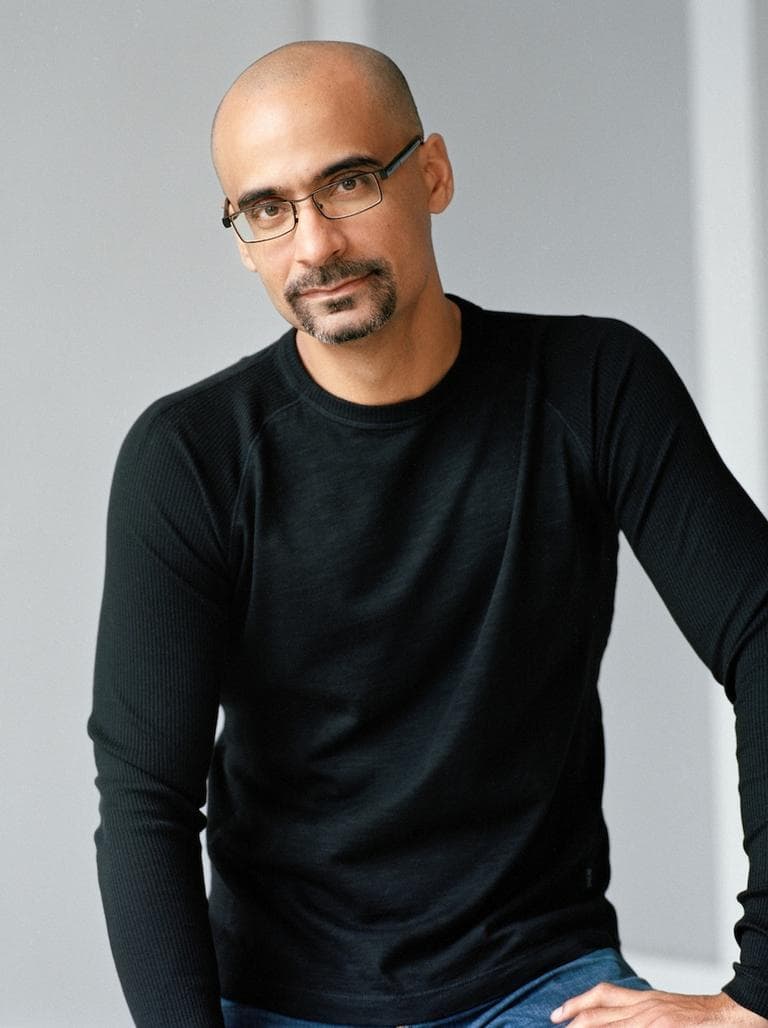

This Is How You Write Seductively

Yunior goes in for sex in a way that might make the legendary Wilt Chamberlain blush.

For good reason. Díaz melds everything from Dominican machismo to tender musings on love and rage against the political machine into a forceful voice of both the Dominican diaspora and the literary quest for 21st century identity. All of that is once again on display in his latest collection, “This Is How You Lose Her.”

His guide/narrator/alter ego is Yunior, the same fellow who tried to convert Oscar from nerdism, obesity and other self-destructive tendencies in the earlier book. Yunior still goes in for sex in a way that might make the legendary Wilt Chamberlain blush. He and other Dominicans in the book trade fidelity for hedonism in a way that borders on the stereotypical. And as the politics in the book are much less overt – Trujillo and his thugs are not a part of this story – “This Is How You Lose Her” might be dismissed as less serious than “Oscar.”

That would not be an accurate conclusion. If the plot of these somewhat connected stories turns on the nexus of love and lust, there is nevertheless the sense of a quest for something deeper. The quest is for a sense of identity in the face of 21st century dissolution — the Dominican diaspora, the death of any kind of over-arching mythology for post-Boomers, generational and ethnic fractiousness — all the ingredients that have won acclaim for writers as diverse as Jonathan Franzen, Jennifer Egan, and Díaz.

Yunior’s obsessiveness about the opposite sex seems joyless, as most obsessions ultimately are. The same for his attempts to find much sustenance in popular culture or ethnocentrism. They get him only so far. Díaz's writing is often celebrated for its earthy embrace of all of the above, but those are, in the scheme of things, minor accomplishments. What makes Diaz more impressive is the underlying acknowledgment of the tragedy underneath that macho earthiness. Díaz’s philandering borders on the suicidal when measured against the loss of love from any self-respecting woman.

I’m not sure how well we get to know Yunior, despite all his reflecting on what went wrong with his love life. Then again, he doesn’t know himself. He begins by stating “I’m not a bad guy” and he isn’t. But there’s seemingly no code of behavior — nationally, ethnically, generationally — that can make sense of his life.

The women of the book fare better in that regard than Yunior. At least they seem to know what the stakes are, particularly Yasmin, who works in a laundry room in a story that doesn’t involve Yunior, “Otravida Otravez.” The depiction of poverty and her methods of coping make this some of of Díaz’s most soulful writing.

It also makes me wonder if Díaz might ultimately be better off relying less on Yunior in the future. Just as most mystery writers do their best writing without a standing detective, Díaz might find richer soil without the encumbrance of an alter ego. I’d love to read a nonfiction book about his experiences teaching creative writing at MIT. Yunior might ultimately play the same role for Díaz that Nathan Zuckerman plays for Philip Roth. In honor of Díaz’s penchant for mixing English and Spanish together, we’ll just say, Nada wrong with that.

Excerpted from THIS IS HOW YOU LOSE HER by Junot Díaz by arrangement with Riverhead Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc., Copyright © 2012 by Junot Díaz

Your girl catches you cheating. (Well, actually she’s your fiancée, but hey, in a bit it so won’t matter.) She could have caught you with one sucia, she could have caught you with two, but as you’re a totally batshit cuero who didn’t ever empty his email trash can, she caught you with fifty! Sure, over a sixyear period, but still. Fifty fucking girls? Goddamn. Maybe if you’d been engaged to a super open-minded blanquita you could have survived it—but you’re not engaged to a super openminded blanquita. Your girl is a badass salcedeña who doesn’t believe in open anything; in fact the one thing she warned you about, that she swore she would never forgive, was cheating. I’ll put a machete in you, she promised. And of course you swore you wouldn’t do it. You swore you wouldn’t. You swore you wouldn’t.

And you did.

She’ll stick around for a few months because you dated for a long long time. Because you went through much together—her father’s death, your tenure madness, her bar exam (passed on the third attempt). And because love, real love, is not so easily shed. Over a tortured six-month period you will fly to the DR, to Mexico (for the funeral of a friend), to New Zealand. You will walk the beach where they filmed The Piano, something she’s always wanted to do, and now, in penitent desperation, you give it to her. She is immensely sad on that beach and she walks up and down the shining sand alone, bare feet in the freezing water, and when you try to hug her she says, Don’t. She stares at the rocks jutting out of the water, the wind taking her hair straight back. On the ride back to the hotel, up through those wild steeps, you pick up a pair of hitchhikers, a couple, so mixed it’s ridiculous, and so giddy with love that you almost throw them out the car. She says nothing. Later, in the hotel, she will cry.

You try every trick in the book to keep her. You write her letters. You drive her to work. You quote Neruda. You compose a mass e-mail disowning all your sucias. You block their e-mails. You change your phone number. You stop drinking. You stop smoking. You claim you’re a sex addict and start attending meetings. You blame your father. You blame your mother. You blame the patriarchy. You blame Santo Domingo. You find a therapist. You cancel your Facebook. You give her the passwords to all your email accounts. You start taking salsa classes like you always swore you would so that the two of you could dance together. You claim that you were sick, you claim that you were weak—It was the book! It was the pressure!—and every hour like clockwork you say that you’re so so sorry. You try it all, but one day she will simply sit up in bed and say, No more, and, Ya, and you will have to move from the Harlem apartment that you two have shared. You consider not going. You consider a squat protest. In fact, you say won’t go. But in the end you do.

This program aired on September 14, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.