Advertisement

Lawsuit, Underage Drinking Test Liability Of Kraft, Gillette Stadium

Resume

In a Dedham courtroom Tuesday, lawyers for Robert Kraft will argue that the owner of the New England Patriots and Gillette Stadium is not liable for the deaths of two young women killed in a drunk driving accident in 2008.

Both the driver and a passenger had spent the day drinking at a tailgate party during a country music festival at the stadium. Both were underage.

Kraft's attorney will compare him to a teenage girl in an unrelated case, who threw a party while her parents were away. In that case, the high court ruled the parents were not liable because they did not supply the alcohol.

The Rowdy Tailgate

On July 26, 2008, Debra Davis, of Milton, and four young friends paid $40 to park their minivan in a lot at Gillette. They did not have tickets to get inside the New England Country Music Festival. They came to tailgate and party.

The stadium held 54,000 fans. In the parking lots there were tens of thousands more, police estimated. Many of them had no tickets to get inside, like 20-year-old Davis, 19-year-old Alexa Latteo and 20-year-old Nina Houlihan.

"We were all mixing hard alcohol with soda or a juice and eventually we were just taking straight shots of vodka, or rum in their case, and then drinking beer," Houlihan said.

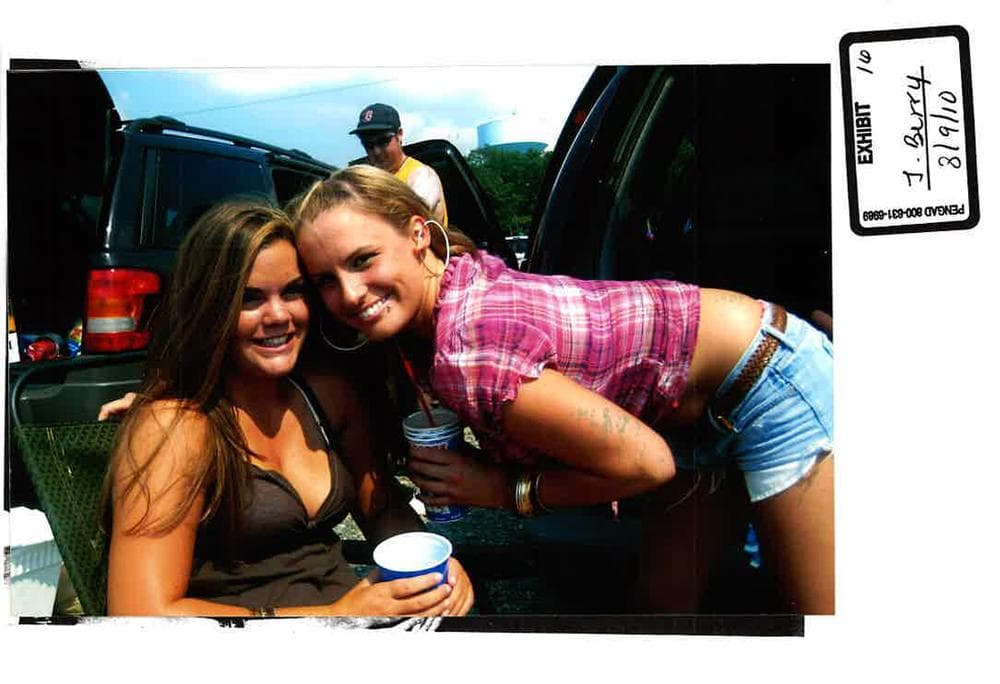

By 2008, the country music festival at Foxborough was gaining a reputation among law enforcement agents as one of the biggest underage binge drinking tailgate parties in New England. The kid drinkers were as conspicuous as their red Solo cups, the drinking games of Beirut or beer pong, the free-for-all — and the mayhem.

Houlihan says the three young women drank with their friends for hours, moving between Parking Lots 11 and 13. Within a couple of hours, she says, she was inebriated, and so was the crowd. It was out of control. Witnesses describe people dancing atop buses. She says guys were brawling, guys and girls were fighting, and they were urinating and vomiting in public.

"It was like a zoo," Houlihan said. "It was crazy. It was just like a party going out of control."

But, she says, no one checked their IDs. No one stopped their games of beer pong or drinking jello shots.

"You never saw any security guards there?" I asked her. "You were never asked if you were underage, if you had a ticket? And you never saw security guards asking that of anybody you were with?"

"No," she said. "None of that. From what I remember, no, none."

Signs on the way into the Gillette lots read "No tickets, no entry." The presence of so many without tickets suggests the policy was not widely or evenly enforced by parking lot attendants.

"We stopped to pay, but nothing to do with tickets. We were all fine," Houlihan said. "We didn't have any trouble."

"Did anybody ever come up to you and ask you if you had a ticket or not?" I asked her. She said no.

The Accident

The day sizzled, just shy of 90 degrees, and then at 6, Houlihan says, security guards and cops showed up to tell everyone without a ticket to get out or be arrested.

"How can you have something host an event where you know that everyone is getting wasted, drunk, inebriated, and then kicking them out?" she said.

Davis got into the front passenger seat of Latteo's car, Houlihan got into the back, and Latteo took the wheel. A mile or so down Route 1, she took a curve at high speed, lost control, and hit a tree. Houlihan suffered multiple fractures and a broken pelvis. She believes Latteo and Davis died instantly.

"I just remember looking in the front seat and seeing, they weren't there anymore," Houlihan said. "I kept tapping them and shaking them, trying to do anything I could and I knew they weren't passed out or had concussions. I just had a feeling."

"It seemed that their necks had been broken?" I asked. She said yes.

Latteo had a blood alcohol content of .24, three times the legal standard of intoxication. Davis' was .20.

So who was to blame? Kraft and his family businesses did not supply alcohol to any of them. The young women brought it with them, they drank it on Kraft property, and chose to drive off while intoxicated. By any standard, the women contributed to the accident.

"Yes, I was negligent," Houlihan said. "Yeah, it is hard to live sometimes, you know, knowing you are the only one." She added: "I wish I had never gone."

The Legal Case

Both Houlihan and Davis' parents are suing the Kraft companies, claiming negligence, gross negligence and willful and wanton behavior. Their attorney, Joseph Borsellino, argues that Kraft and his companies are just as liable as if Kraft had sold the three women alcohol.

"Supplying alcohol, furnishing, means to allow underage drinking to occur, whether you actually hand the alcohol to the party or sell it to them or not," Borsellino said. "If you are allowing them to underage drink on your property and you're not doing enough to prevent, you are now furnishing them alcohol."

That is the criminal standard for “furnishing” in Massachusetts. The civil standard is much narrower. It has a bright line test. The lawyer for the Krafts cites a recent ruling by the state's highest court, called "Juliano." It's the case of a teenage girl who threw a party while her parents were away. One of the guests drove off drunk and crashed, causing permanent injuries to his passenger. The court found the parents were not responsible because neither they nor their daughter supplied the alcohol.

But, Borsellino argued, "in the Juliano case there was no fee for entry. It was not a profit-making activity. In the country music fest it was just the opposite. The profit-making activity brings along with it the duties and responsibilities to keep the property safe."

And unlike the 19-year-old hosting the party in the Juliano case, Borsellino argues, the Krafts had the means or ability to control these underage drinkers at the music festival.

"In the country music festival, in contrast, the owners of the property had an 800-man security force," Borsellino said.

The two lawsuits draw a picture of CEO Robert Kraft and his group with their heads in the sand about underage drinking. Just a year before the deaths, in 2007, violence, vandalism and underage drinking at the festival led Foxborough selectmen to suggest it was a "riot." The police and fire chiefs said that tailgating and underage drinking were the major issues; what was once acceptable had become "an impossibility."

By July 26, 2008, underage binge drinking could no longer be a surprise. But, according to testimony, the Kraft Group added a thousand more parking spaces in lot P11, and it had no more than two guards who said they didn't patrol.

"The testimony of the security guards and the kids is unanimous," Borsellino said, "that no one from the Kraft companies stopped and inquired of a single one of them at any time throughout the day."

We tried to get comment from the Kraft Group. On Monday, Douglas Fox, the Krafts' main attorney in the case, stated it's long-standing practice not to discuss current litigation.

The Family's Case

"As soon as we lost Deb, I used to stand in front of refrigerator and cry and look at my Deb's picture," said Maryann Davis, Debra's mother.

"I said, 'You know what, Deb? I promise that I'm going to do everything in my power to spare another family from going through this suffering.' "

By the way, if you think you've heard the name of Debra Davis before, you probably have. She was named after her aunt, who was allegedly murdered by James "Whitey" Bulger. Her father, Steven Davis, who's had more than his share of loss, vows he will take this lawsuit to the very end.

"Bob Kraft and Jonathan could put a stop to this thing on a phone call," he said. "Two words: Stop it. They have the power. They own it."

In Superior Court Tuesday, the attorney for the Krafts will seek to have the lawsuits dismissed summarily.

This program aired on November 20, 2012.