Advertisement

Gaps Found In Care, Safety In Mass. Group Homes

ResumeA joint investigation of the New England Center for Investigative Reporting and WBUR (Part 1 of 2. See Part 2).

BOSTON — Valerie Diaz’s worst fears were realized when she opened the door to her Connecticut home in June to find grim-faced police officers on her front stoop.

“They said, 'Well, we have to inform you that your daughter, Malissie Holloway, was found dead in a closet,' " Diaz said. “I just kinda went into shock after that.

“I still can’t understand why,” Diaz said. “I don’t understand why.”

Her 24-year-old daughter, an ambitious singer afflicted with debilitating mental illnesses, had been found by workers at the Somerville, Mass., group home where she lived, dangling from a pipe. Her family is now questioning how closely Holloway was supervised at the home, run by a private vendor hired by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health.

“I don’t know how she reached that pipe that was like 12 feet in the air. I don’t know how she was able to get a slipknot,” Diaz said. “I have more than my share of questions.”

An ongoing state investigation into Holloway’s death comes as DMH strives to shore up its battered community mental health system, the subject of two critical oversight reports issued in the past 18 months that highlight deep fissures in client care and worker safety. The largest component of a state mental health system providing treatment to over 29,000 people, Community Based Flexible Supports, or CBFS, has come under intense scrutiny following the 2011 slaying of Stephanie Moulton, a 25-year-old Revere group home worker, allegedly killed by a client with a long history of violence.

DMH Commissioner Marcia Fowler said the state, poised to release its own performance report this month, has made significant progress in implementing recommendations made by a special state task force convened after Moulton’s murder. More than 1,600 direct care workers have received personal safety training and DMH is working with state corrections officials to better track released inmates in need of mental health services. CBFS client progress is also being more closely monitored. CBFS works better than ever, Fowler said.

“I think it’s a great model,” she said of CBFS. “I have confidence in the folks that deliver services to the people we serve. I also have confidence in hearing from the people we serve. They’re very vocal advocates for themselves, letting us know what’s working, what’s not.”

Support for the system also comes from lawmakers, mental health vendors and advocates who believe clients fare far better in community settings than being locked away apart from the rest of society.

But a joint investigation by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting and WBUR reveals that six months after Holloway’s suicide and nearly two years after Moulton’s death, the CBFS system is still seriously flawed. Workers and mentally ill clients alike are fearful about understaffing and their personal safety, and there remains a chronic lack of funding to support the mammoth CBFS network, the investigation found. Meanwhile, there are deepening concerns that local police as well as the broader criminal justice system are being increasingly relied upon to intervene as default mental health providers, the investigation found.

The union representing over 12,000 human service workers statewide said calls to police for help at community-based mental health facilities should be the exception, not the rule.

“If a home is properly staffed, and if the clients served are receiving the treatment they need, it should be very rare that anyone in the home would have to call police,” SEIU 509 spokesman Jon Grossman said. “So an increase in calls suggests that proper staffing or treatment isn’t being provided.”

The investigation’s findings are based on interviews with dozens of direct care workers, as well as DMH clients and their families, lawyers, mental health advocates, vendors and state officials; an analysis of thousands of police calls; and a review of more than 1,000 pages of court documents and records released by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Hazard Administration.

Feeling unsafe on the job is a cold, hard fact, some workers said.

“Something like that could easily happen to us,” said Noah Campbell, speaking of Moulton’s murder. For the past three years, Campbell, a member of Service Employees International 509, worked as a counselor for Alternatives Inc., a CBFS vendor providing mental health services in western Massachusetts. “And I don’t think there is anything to prevent that.”

Former DMH Commissioner Marylou Sudders, now an associate professor at Boston College’s Graduate School of Social Work, said CBFS is “great in theory and still a work in progress in practice.”

“I would say the department, in switching to the CBFS model, has not put in the correct level of checks and balances around licensing, reporting and the like, which is really a state responsibility and not a provider responsibility,” Sudders said.

Staffing Shortages, Client Care And Safety Fears

Following Moulton’s murder, state officials vowed to improve the community mental health system, including addressing staffing shortfalls and the quality of client care. Both issues were part of a sharply worded 42-page report (PDF) the task force issued in June 2011 highlighting serious safety gaps throughout the system.

“We heard repeatedly from provider organizations that the system has serious deficiencies in staffing and covered services, most notably clinical care . . .” the report states.

But the DMH investigative report into Holloway’s death at a Somerville group home operated by VinFen shows staff there failed to notice her missing for more than two days.

“. . . despite residential staff’s awareness that client had not been seen and therefore missing for nearly sixty (60) hours, no staff at any point in time, including the Program Director, notified the police,” the report states.

The report also states that staff seemed more concerned for “client’s privacy with seemingly little thought given to actual safety risks.”

“That’s the sad part, that she could have been there for two or three days and nobody noticed,” Holloway’s mother, Diaz, said.

VinFen CEO Bruce Bird called Holloway’s death a tragedy.

“It’s a tragic fact that even though there have been lots of improvements in technology to help us intervene and help people in recovery with clinical services, we still don’t have the clinical methods we need to prevent suicides,” Bird said.

Questions about staffing are at the heart of the Moulton case. Moulton was working alone when she was allegedly beaten and stabbed by Deshawn James Chappell, 27, in a home for the mentally ill run by North Suffolk Mental Health Association. Moulton’s mother, Kimberly Flynn, said her daughter was unaware of Chappell’s violent history when she was killed.

There were warning signs the already fragile system was in distress. Newly released DMH records show there was a marked increase in “critical incident reports” — like safety violations or violence — from mental health facilities between January 2009, just before CBFS launched, and February 2011 — less than a month after Moulton’s death — a red flag DMH failed to heed, the task force report noted.

And the unease about safety is not limited to workers. Longtime DMH clients are anxious as well.

“I’ve been in fights. I’ve seen fights. There are times when you feel uncomfortable or at risk. I don’t think anyone should have to feel like that,” said client Brian Lane, 24. Lane has lived in various group homes over the past three years and said police were frequently called in.

Continued Chronic Underfunding

The CBFS system is a mammoth operation, serving nearly 14,000 in hundreds of group homes, clubhouses, private apartments and day shelters statewide. The state pays 19 vendors about $245 million annually to run CBFS programs, Fowler said. But adequate funding remains a core shortcoming. While $10 million was added to this year’s fiscal budget for the CBFS program, overall the DMH budget is $55 million less today than it was in 2009, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. State mental hospital beds have shrunk from 2,272 in 1990 to just 626 today, studies show.

The Disability Law Center, which advocates for the mentally ill, said 94 percent of those released from the closing Westborough State Hospital in 2010 went into the CBFS system, placing a burden on vendors to provide quality care without increased funding.

“Our conclusion is that when you privatize human services under the best system, a portion of the available dollars go to administrative costs, which I believe take away from the needs of the individual,” said DLC attorney Walter Noons. “There is clearly a lack of resources to do the job sufficiently.”

The June 2011 task force report also faulted DMH for repeatedly slashing funding for the community mental health system, leaving employees like Moulton working alone and at risk. The task force urged DMH to act.

“The recommendations in this report focus on fundamental safety concerns. Delays in implementation could result in otherwise avoidable adverse outcomes,” the report states.

Task force members declined interview requests, deferring questions to DMH.

Safety remains in the forefront of the mind of workers like veteran mental health counselor Tony Xaste, 53, who works at a Worcester group home run by Community Health Link. Xaste is the union steward for the SEIU, which represents 12,000 human service workers statewide. He said it’s nerve wracking to work solo shifts, and he has had to call police at least 10 times in the past three years when situations have become uncontrollable.

“Sometimes we work in fear," Xaste said. "Sometimes it’s just unbearable."

The dangers aren’t limited to staff. “The people in the program are at high risk,” he added.

Xaste said he doesn’t blame his employer, but rather the state for failing to provide enough funding to support CBFS vendors, especially when it comes to training.

“We are not trained properly to do the work. Only some of us have experience,” Xaste said.

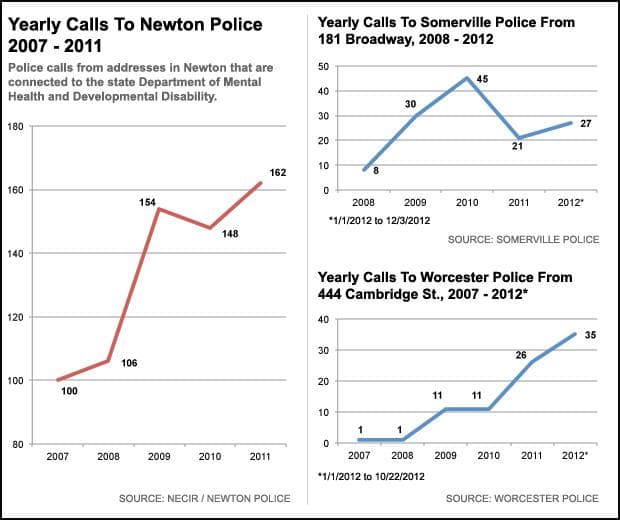

Worcester police records show that before CBFS, police were called to the home where Xaste works once the entire year, but through October of this year they were called 35 times.

Fowler said requests for police assistance to CBFS addresses have been in “sharp decline” since 2008, but did not provide data to support the claim. Police data from some communities, such as Newton, Somerville and Boston, shows that calls for police help have risen since the implementation of CBFS.

Between 2009, when CBFS took effect, and 2012, police calls to the group home where Hollway was found dead in June rose threefold, Somerville police said. A new state grant to help train officers and dispatchers how to handle mental health calls will help police respond more effectively, said Somerville Police Lt. Gerald Reardon.

In Boston, police Commissioner Edward Davis said his officers are increasingly relied on to deal with mental health issues both in DMH facilities and on the streets.

“Our call volume on mental health issues is substantial,” Davis said. “It is certainly becoming more acute.”

In Cambridge, where calls to CBFS addresses have remained steady in recent years, a need for help from people living on the street is increasing, said Sgt. Kathleen Murphy.

“What I try to say is, ‘You’re a social worker with a gun’,” said Murphy, who trains police staff in how to deal with mental health calls. “We are the so-called first responders.”

The department is preparing for intensive mental health training to aid police staff in helping diffuse a tense situation and get help for the mentally ill individual.

“It’s not what you see on TV and go into bang, bang, shoot-em-up. A lot of it is dealing with people in crisis,” Murphy said.

The Criminal Justice System As A Satellite Provider

Other CBFS critics said the lack of training coupled with a flawed understanding of the complexities of mental illness are creating unnecessary dangers.

To Steve Definis, CBFS represents a fractured and ineffective way of dealing with his son’s mental illness. Chris Definis, a 22-year-old bipolar addict, has been in 19 different state mental health facilities in the past three years, ricocheting from group homes to sober houses to hospitals. Workers’ lack of training, including recognizing when his son was spiraling out of control, is central to Steve Definis’s complaints. He and his wife sent emails to workers at a facility Chris was housed in in July warning the staff they felt he was “faltering.” Within days Chris overdosed on heroin.

After a five-week hospital stay, workers took him off his medications and discharged him, Steve Definis said.

“They released him at 10 in the morning and let him sit there and wait for a ride until almost 10 at night,” said Definis, who later filed a complaint with DMH. “They never did look or take into consideration a repeated diagnosis of mental illness . . . I would be perfectly happy with a diagnosis of not mentally ill but that’s clearly not the case.”

Steve Definis claims DMH is increasingly relying on the criminal justice system as a satellite mental health treatment provider. Multiple times this year, Definis’ son has been jailed after sinking back into drugs and erratic behavior following his release to the streets from DMH facilities.

“I spoke to the probation officer on April 12 and said, ‘You’re putting a mentally ill person in jail,’ ” Steve Definis said. “The probation officer was understanding but said it’s the only tool they had. They had no other place to put him.”

The inability of the state system to deal effectively with Chris Definis’ chronic issues has forced his heartbroken parents to spend weeks trying to track him down to make sure he is safe.

“There was a time when I was in the dark. You walk down the street and see someone who is mentally ill and you don’t think ‘that’s somebody’s son or daughter or whatever’,” Steve Definis said. Steve’s wife once found their son sleeping in Harvard Square, eating chestnuts and laughing to himself.

“We couldn’t recognize him at first. He was very thin, he was ill, he was not rational or coherent. You couldn’t carry on a conversation with him,” Steve Definis said.

DMH Commissioner Fowler disagrees that CBFS is not working properly. She praised the system as nimble enough to adapt to a client’s changing mental health needs, something the previous structure did not. Many of the task force recommendations are close to being implemented, except increasing the agency’s budget by $100 million, she said.

“In terms of consumer satisfaction, the people we serve are happy with their engagement and level of treatment,” Fowler said.

“It’s incumbent upon us to provide services to everybody who needs them and we need to do the best job we can with the money appropriated from the Legislature,” Fowler said.

Meanwhile, Holloway's family waits for answers. For more than a decade, Holloway, who struggled with bipolar disorder, had bounced around state facilities until she arrived at the VinFen home in Somerville in 2009.

“We’re just trying to piece together what happened to my baby,” Holloway’s mother said.

Audio report by WBUR's Deborah Becker; Web report by Maggie Mulvihill. The New England Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit newsroom based at Boston University. Jillian Sandler and Sydney Lupkin of NECIR contributed to this report.

This article was originally published on December 18, 2012.

This program aired on December 18, 2012.