Advertisement

Cézanne and Gauguin Side By Side: Which Way Would 20th Century Art Go?

In retrospect, the two major late paintings by Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin represent a fork in path of 20th century art.

“It is one of the greatest French paintings in the United States. It’s Cézanne’s masterpiece,” says Emily Beeny, assistant curator of European paintings at Museum of Fine Arts, of Cézanne’s 1906 painting “The Large Bathers,” on view at the museum (465 Huntington Ave., Boston) through May 12. It’s on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art part of the MFA’s “Visiting Masterpieces” series.

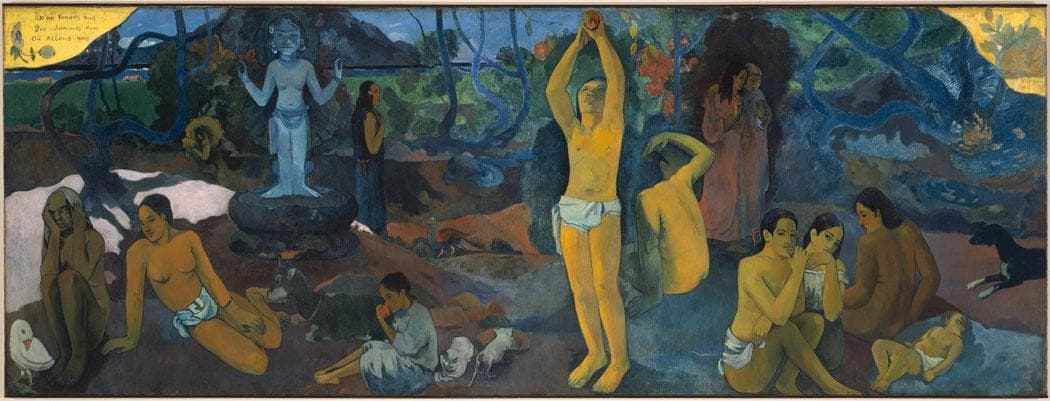

Hung to the right of it is the MFA’s own iconic Gauguin, “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” from 1898.

“Which is arguably Gauguin’s greatest masterpiece as well,” Beeny says. “And like the Cézanne it is conceived as a last great painting.”

“What,” Beeny asks, “does that tell us about what they hoped would come next?”

Gauguin’s 12-foot-wide panorama is a sensual dreamscape of nearly nude Tahitian women in a warm, idealized tropical landscape. The artist intended it, at least in part, to be an allegory of the stages of life—infant at the right to old woman at left. But it doesn’t resolve as simply as that. The careful groupings of figures and cats, goat, birds and dog, plus a blue figurative statue, suggest both actual observation of people and myth making. It’s psychically and sexually charged, tapping into what Gauguin called “the mysterious centers of thought.”

Cézanne paints 17 nude white women densely packed along the shore of a body of water in the 8-foot-wide “Large Bathers.” They and a town on the other side of the water are framed at either side by tree trunks that arch toward the center. Gauguin’s women stare out at us or seem to stare off, lost in thought. Cézanne barely sketches in his women’s facial features. They’re types, not individuals. The whole painting is schematic. And its cool blues and greens contrast with the sultry golds Gauguin chooses to paint flesh.

“The Cézanne is so distant from any carnal meaning,” Beeny says.

“It’s a tough painting,” she adds. “It’s not necessarily as easy to enjoy.”

“We can see Cézanne changing his mind about things actually on the canvas,” Beeny says, “and that contributes to the strangeness of the figures and makes it so boundlessly fascinating.” In particular, she notes how the arms of the woman at the far right look like they were once the legs of another woman behind her, and not yet fully transformed into their new role. “We get more of a sense of his kind of struggle with the nudes.”

One might trace Gauguin’s stylistic influence to Matisse or the Surrealists. But Cézanne’s formalism—his focus on the way he paints (“He uses almost facets to built up tones,” Beeny says) over what he paints—would become the predominant mode of Modernist painting.

“I think at the end of his life in Cézanne we see him reaching a painting of abstraction and serenity and a kind of classicism,” Beeny says.

“He very much looks forward to the experiments of the next generation of painters,” she says, “particularly Picasso, whose ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’ appears in 1907, the year after Cézanne’s death.”

This program aired on February 18, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.