Advertisement

Adjunct Instructors In Boston Area Rally To Unionize

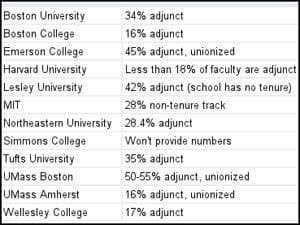

ResumeAdjunct instructors are sometimes called the temps of the world of academia. Colleges and universities rely heavily on them, but adjuncts are paid much less than full-time and tenured professors, often get no health insurance or other benefits, and have little job security.

So there's a movement under way to unionize adjunct faculties in the hopes of improving pay and working conditions. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) has started a movement called Adjunct Action and will be meeting this weekend in Boston with adjuncts from more than 20 area campuses to talk about raising standards for adjunct professors.

WBUR's All Things Considered host Sacha Pfeiffer spoke about this campaign with Deborah Schwartz, an adjunct faculty member in the English department at Boston College, and Anne McLeer, the director of research and strategic planning for the SEIU who's helping organize adjuncts around the country.

Pfeiffer: Deborah, "adjunct" typically means someone who's paid by the class, but the word seems to have different meanings at different institutions. Can you explain what it means in your case at BC?

Schwartz: Well, it means exactly that: You're paid per class, you have no benefits, you don't have a contract, you don't have job security. And I think the big thing is you don't know what your schedule is going to look like. You don't know what your workload is going to look like because you are not given a formal contract.

And you could be asked at the last minute to teach a class or told at the last minute, "We actually don't need you"?

Schwartz: I've had that experience — a call on Labor Day weekend. "We need someone to fill a Comp 2 class. Can you come in on Tuesday?"

And on short notice you have to decide if that's realistic and if you can pull together a syllabus?

Schwartz: Right.

Anne, would you explain what you mean when you call someone an adjunct?

McLeer: It depends on the institution. Fifty percent of faculty in all the institutions of higher ed in our country today are part-time, and that's up from 34 percent in 1987 and 22 percent in 1970.

And why has the use of adjuncts increased so much?

McLeer: It saves the universities a lot of money. I would argue that the institutions of higher education have kind of become dependent on this cost-cutting scheme that has just sort of expanded.

Deborah, would you share with us what you are paid to teach courses as an adjunct and whether you get any benefits at BC?

Schwartz: I'm looking at an annual paycheck from Boston College, teaching two intensive writing courses, two per semester, at $36,000 annually. That doesn't include health insurance or benefits because I haven't worked there long enough to receive those. So the way I supplement it is I have another 30-hour [weekly] position that offsets that and covers my health insurance.

And how much are you paid per course at BC?

Schwartz: It's about $5,900 per course.

Anne, how does Deborah's pay as an adjunct compare to other adjunct paychecks you hear about around the country?

McLeer: I have to say that's on the high end.

Schwartz: It is on the high end. Very high.

McLeer: The average is like $2,500 to $2,900. We improved the pay at George Washington University. When I was teaching there in the English department I was getting $2,700 a course.

What year was that?

McLeer: That was 2007. With the first union contract, that increased by $1,000. But it's still very much not where it should be.

We should clarify that George Washington unionized its adjunct faculty, which is why you were able to get that raise.

McLeer: Yes. We had a successful union election in 2004 and negotiated our first contract, which is when we were able to get that raise.

Did that help with other benefits as well?

McLeer: Oh, absolutely. We were able in our contract at George Washington University to get protections on being rehired to your course. We were able to get a fair and more transparent evaluations procedure where now there's a classroom observation, you can contribute materials to your evaluations file, and you're evaluated in a broader sense rather than just by the students, which added to the sense of job security and ability to access true and meaningful academic freedom, I would argue.

Deborah, many people may say that in a tough economy people often have to piece together work. And they may also say that if you're not a full-time faculty member with a PhD, you should expect that you'll be compensated at a significantly lower rate.

Schwartz: Many of my adjunct colleagues do have PhDs and 20 years of teaching experience and publications. I myself have an MFA. I have publications, so I look on paper like many of my other adjunct colleagues, who look like many of my tenured colleagues. But the difference is when a university is asking $50,000 a year and receiving it.

From students in tuition?

Schwartz: From students in tuition. One wonders where the money's going and why it is not going in instruction, where there's a systemic problem, where a majority of the folks who walk into their first-year English class are going to be taught by adjuncts.

And this is an important part of this issue. Anne, would you say there's an adverse impact on teaching quality or students aren't getting what they're paying for when it's heavily an adjunct faculty?

McLeer: Absolutely. And I want to make it really clear here [that] it's certainly not because part-time faculty are not excellent teachers. But the reason that the overuse of part-time faculty and adjuncts affects student success is because of the bad working conditions. You don't have that much time to speak to students because you're rushing off to teach a course somewhere else or to another job. You don't have that much interaction with other faculty. You're excluded, in many cases, from departmental decision-making.

Schwartz: One example of what I think Anne's talking about: I have a standing date on Thursdays with five students where we talk by cell phone and we're looking at their papers for 20 minutes each because they don't have access to my office hours. And I think many, many faculty end up doing very creative — and perhaps a little bit oddly boundaried — interactions with students so that we can get to their work.

This program aired on April 10, 2013.