Advertisement

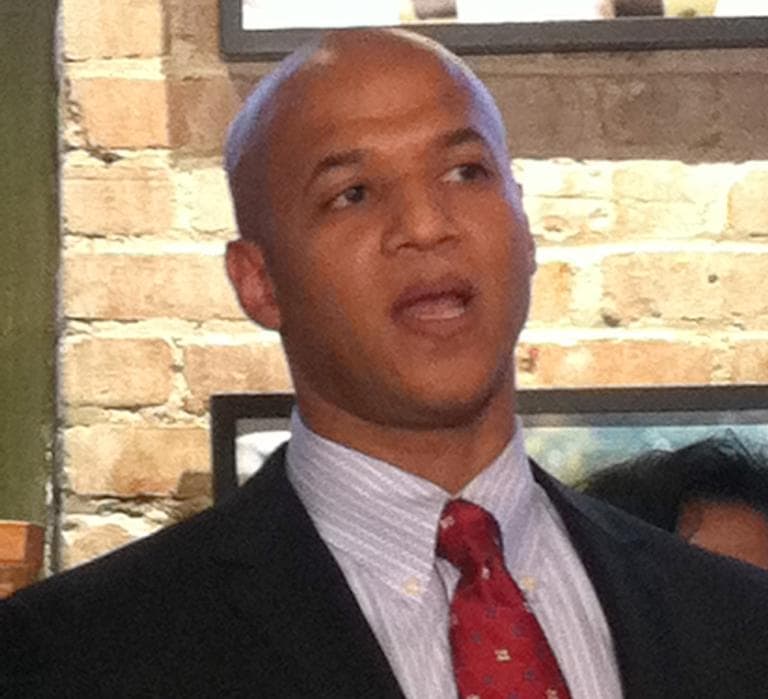

For Barros, A Neighborhood As Source Of Strength — And Weakness

Mayoral candidate John Barros stood in the Dennis Street Park in Roxbury, a small fountain gurgling behind him, and pointed to the trim houses on the edge of the green.

"This whole area was vacant," he said.

Arson, abandonment, illegal dumping: all of a piece with the 1960s- and '70s-era hollowing out of the American inner city.

The transformation of the area — a park, affordable housing, a greenhouse sprouting tomatoes, squash and cucumbers — is in no small part the work of the nonprofit Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative. And Barros has been in and around the organization for 25 years now.

He volunteered for DSNI at age 14, won election to the board three years later and became executive director in 2000. And his story of a place reborn — if still troubled — is among the most compelling in the 12-person race.

But in an election where place matters even more than usual — in an election shaping up as a territorial, neighborhood-by-neighborhood scrum for votes — it's unclear if the place that provided Barros with an identity can deliver the political might he'll need on election day.

'The Street Is The Street'

Barros, 39, is the son of Cape Verdean immigrants.

His father started in the cranberry bogs of Cape Cod, working for pennies an hour, before he moved to Boston and met his wife. The pair settled in the Dudley neighborhood, working on assembly lines turning out rubber products and electronic components.

Barros says the popular conception of the Roxbury of his youth was incomplete and distorted, but not entirely off-base. "Oh, no question, it felt dangerous," he said. "The street's the street."

Young men joined gangs. They flashed colors. And riding the train or bus, he said, was a tricky proposition.

But Barros excelled in school, graduating from Boston College High School and attending Dartmouth.

After college, he went to work for the Chubb Group of Insurance Companies, analyzing tech companies like Priceline.com and Amazon.com. But he frequently traveled home from New York on the weekends.

Advertisement

By the time he took over DSNI, first as an interim executive director in 1999 and then as the official chief a year later, the group was scaling down — a big, national grant coming to an end.

The challenge, he said, was to shrink the place while keeping it relevant: building the greenhouse, helping to erect more affordable housing and co-founding a charter school.

One of Barros's main arguments for his candidacy is that he's one of the few would-be mayors who has actually managed something. Who has engaged a whole community. Who has done place-making.

"I want to take this to scale," he said, driving down Dudley Street on a recent Saturday afternoon. "We can do it in all neighborhoods."

Barros's management record is not unblemished. A Cape Verdean restaurant he co-founded with two brothers and a cousin, Restaurante Cesaria in Dorchester, struggled financially and landed on a payment plan for back taxes; his campaign chalks up the problem to a switch in payroll companies, with the new firm failing to withhold from paychecks for a time.

But the candidate has framed the experience as a window onto the struggles of small business. And he says the restaurant was less a business investment than a community builder.

That focus on community building is central to his campaign. Driving from one campaign event to another on a recent Saturday, Barros lauded departing Mayor Thomas Menino for operating city government effectively. "[But] I think we can do a better job at getting more people to the table to help, be more inclusive, engage more young people — and really maximize the new Boston," he said, using a catch-all phrase for an increasingly diverse city.

It is language that plays well among community organizers. But it is not the stuff of headlines.

Neither is his nuanced take on education, a signature issue for the former Boston School Committee member.

"It's not hard line — 'I'm here to support charter schools' — it's not hard line — 'I'm here to support traditional schools,' " he said. "It's really, 'I'm here to support schools that work.' "

It's the sort of formulation, he allowed, that has not satisfied either the well-heeled, pro-charter education reform movement or the unions with a more traditional view -- both potentially important players in the mayor's race.

'He Needs To Make A Move'

Jeffrey Berry, a political science professor at Tufts University, said Barros' failure to stake out headline-grabbing positions — paired with poor polling and fundraising results in the early going — could prove fatal to his campaign.

"He needs to make a move and attract some attention soon, because he may be discounted," Berry said. "Candidates can get caught in a downward spiral where they're not doing well, so people then start hesitating to support them because they don't want to waste their vote."

The political scientist also suggested that Barros' Cape Verdean ancestry may not be as potent at the ballot box as that of other minority candidates in the race — former state Rep. Charlotte Golar Richie and City Councilor Charles Yancey, who are African-American, and City Councilor Felix Arroyo, who is Latino.

At least some minority voters, moreover, worry that there are too many candidates of color in the race.

"There's too many blacks running," said Henry Jones, 60, a blunt-spoken retired firefighter waiting for a bus in Dudley Square one recent afternoon. "They're going to split the vote."

Barros rejects talk of a campaign-within-a-campaign among the minority candidates. But he does acknowledge the realities of political geography.

Golar Richie, who lives nearby, has signs sprinkled along the Dudley Street and looming over Dudley Square. And neither of the candidates can afford to splinter a neighborhood where votes are relatively scarce; in the preliminary mayoral election four years ago, the ward enveloping the Dudley Street corridor produced the fewest votes of all the city's 22 wards.

So energizing the neighborhood, Barros acknowledged — winning it and boosting turnout — is vital if he is to survive the Sept. 24 preliminary election, which will narrow the field to two.

That was the aim one recent weekend afternoon when he descended on a Dudley Street barber shop, shaking hands and chatting with customers in Cape Verdean creole as a soccer game played on the television above.

"This," Barros said, "is where the word gets spread."

It was the latest stop in what Barros is calling his Stand Up Now campaign, designed to meet voters where they are — in barber shops, in churches and on street corners — and get them involved the race.

For Barros, this sort of face-to-face contact — this constant engagement — is the key to overcoming his natural disadvantages.

The aim is to enlist civic leaders, in his neighborhood and beyond, and get them out talking to their friends and co-workers — generating buzz in an organic way.

This intense focus on grassroots organizing was a pillar of Deval Patrick's gubernatorial victories and Elizabeth Warren's successful campaign for the U.S. Senate last year.

And Barros' campaign manager, Matt Patton, was in the thick of both political operations — serving as deputy field director on Patrick's re-election campaign and field director for Warren.

Patton, though, is not the only member of Patrick-Warren diaspora working on the mayoral race. And his candidate is hardly the only one who believes the campaign will be won on the ground.

Barros' charge, then, is to do it better. To linger longer at events. To turn the community organizing skills he's built on the vacant lots and back streets of a tough neighborhood into something more.

His task is to take the story of a forlorn area turned brighter and spread it, one voter to another.

He's got seven weeks.

This program aired on August 5, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.