Advertisement

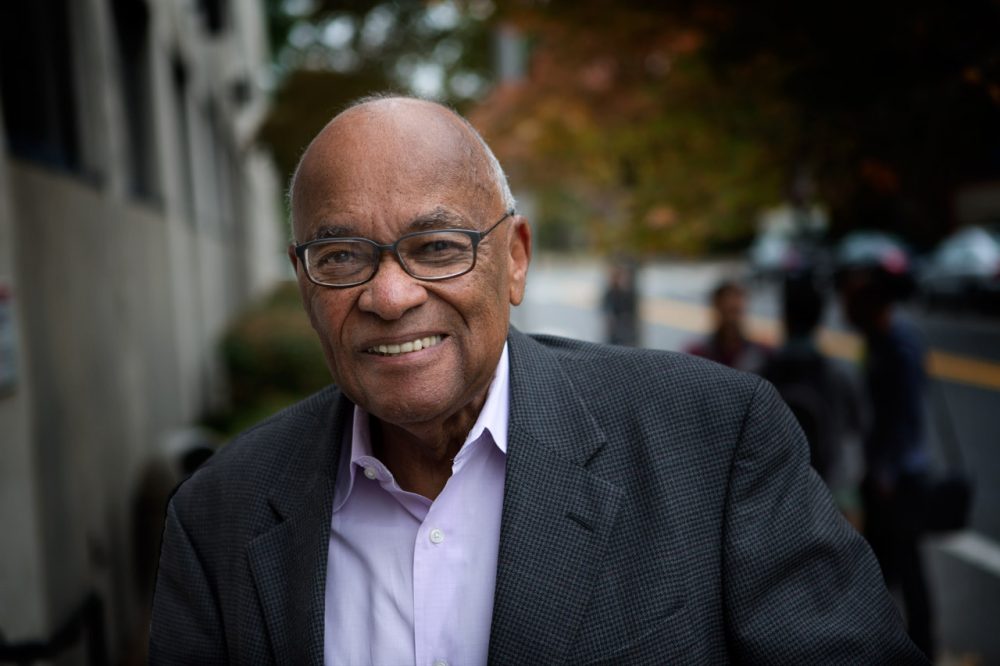

'An Agent For Social Change,' Hubie Jones Has Shaped Boston For 60 Years

For nearly 60 years, Hubie Jones has worked as an agent for social change and social justice in Boston, playing a role in the formation and leadership of some 40 organizations that provide families and their children with the tools to live stronger, more productive lives and enrich their communities.

One of those organizations — the Roxbury Multi-Service Center, one of Boston's oldest social service agencies — will honor Jones, their former executive director, at a gala Thursday night.

At 80 years old, Jones' visionary actions are still shaping Boston, helping it to live up to its ideal of being "a city upon a hill."

Using Scholarship To Advance Public Policy

Jones grew up in the South Bronx in New York City. His father was a pullman porter, his mother a stay-at-home mom who eventually went back to school and became an educator. Jones says his mother wanted her six children to be ambitious despite living in a neighborhood that was breaking under the weight of drug trafficking and fighting gangs.

"I fortunately missed the gang period because I was too young," Jones said. "And by the time I was a teenager, when I would have been approached to be involved with gangs, the gangs were zoned out on drugs. They were gone. They were glassy-eyed on heroin, just around the neighborhood."

"If we begin to get education right, if we begin to get the integration of services right, we can do what no other city probably can do. We have a chance to be spectacular. This is what I live for."

Hubie Jones

Jones initially thought that he'd be a teacher, just as his five sisters were. But his plans changed when the work of one of his professors at City College of New York, Kenneth Clark, was quoted in the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision.

"So this was like a heady experience for me," Jones said. "For me this was powerful because I saw an academic, I saw a scholar using his scholarship to advance public policy and social change."

Jones came to Boston in 1955 to pursue his master's degree in social work at Boston University. A year later he attended a Ford Hall Forum speech delivered by a young minister, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who at the time was making a name for himself in the civil rights movement.

"It was October 28, 1956. I'll never forget the date. And Dr. King came on, he walked up to the podium without a note and out of his mouth came this extraordinary oratory that blew me away," Jones recalled. "It was a part of cementing my commitment to work for social justice and social change in America."

Advertisement

As a young social worker at the Roxbury Multi-Service Center in the 1960s, Jones led a task force which produced a headline-grabbing report showing that thousands of children were being excluded from Boston Public Schools because they either didn't speak English or had been branded as unteachable because of behavioral problems or physical handicaps.

That task force report led to groundbreaking legislation on Beacon Hill.

"The legislation created the first bilingual education law in the nation, and the first special education law in the nation," said Jerry Mogul, executive director of Mass. Advocates for Children, an organization founded by Jones that became a model for Marian Wright Edelman's national organization, the Children's Defense Fund.

That was just the start of Jones' impact on the Boston community.

"The list of people he has mentored is unending, it is unending," said Frieda Garcia, who counts herself among them. In the 1960s as a new immigrant from the Dominican Republic, she was hired by Jones at a time when more Hispanics were moving to Roxbury.

"Hubie was determined not to have repeated what had happened in Harlem. That is, the tensions between Latinos and blacks. And that was one of his goals. So he set me off to find out who were the agencies and what was going on in the Hispanic community," Garcia said. "And when I came back I did a report to the board and the decision was made to support an agency that was just starting, the Spanish Alliance, Alianza Hispana."

Garcia was hired as the first executive director of the organization.

An Agent Of Social Change

Jones went on to become the dean of Boston University's School of Social Work, the first African-American in that role. He held the post from 1977 to 1993.

It was while he was dean at BU that a couple of Harvard students managed to get an appointment.

"We walked in and he kind of looked at us and said, 'Wait a minute, you guys don't go to school here. Who are you?'" recalled Alan Khazei, one of the co-founders of City Year. They were there seeking advice. "And so we quickly went into our spiel. Well, you know, graduated Harvard Law School, Harvard Business School, want to start this urban Peace Corps. We think it can to change the world. Boston is a great place to do it. And we're like talking a mile a minute. He was like, 'OK, slow down, you've got my attention.' We were there for two hours. He was incredible."

"You literally can't scratch the surface of anything in this community that's of any value and not find Hubie Jones was at the center of it," said Michael Brown, another co-founder of City Year, which is now in its 25th year.

For many, Jones became a familiar face for his weekly appearances as a regular progressive voice on a WCVB-TV opinion show, a role rare for African-Americans even today.

Communications consultant and political blogger Marjorie Arons-Barron worked with Jones for 20 years as a producer and and fellow panel member.

"Hubie's whole career has been as an agent of social change and he may be one of the most prominent instruments of social change in Boston in the last 60 years," Arons-Barron said.

Jones understood the power of television and its reach in helping to foster understanding. "I lived to get people to take in information that would get them to think in a different way," he said, "that's what the power of the program was."

Jones has recently expressed concern that despite the number of organizations out there today helping young people in inner cities, we're seeing the same problems with negative indicators that are worse now than what he saw in the 1960s.

"So we don't need more agencies. We've got enough probably. We need to make sure that they are integrated, working with each other, coordinating with each other and leveraging what they do to get really powerful results," Jones said.

That's the impetus for his most recent project, Higher Ground. It's modeled after the Harlem Children's Zone, which seeks to improve the lives of children in low income families by maximizing the coordination of services.

'This Is What I Live For'

Of all of his contributions, though, perhaps the one that makes him most proud is the Boston Children's Chorus.

It's an idea he wanted to bring to Boston after witnessing a performance by the Chicago Children's Chorus more than a decade ago.

"On to the stage came a very diverse group of primarily high school kids singing at a level of excellence that most adult choirs could not sing at," Jones recalled. "There it was, a diverse group using music and the power of music to achieve social integration of young people."

Starting out with just one chorus of 30 singers, the Boston Children's Chorus now has 12 choirs and 500 singers from across the region.

At a White House ceremony last fall, the chorus was awarded the nation's highest honor for youth arts and humanities programs.

"I just want this city to be as inclusive and as great as it can be. We have so many resources in this city in terms of intellectual capital, the universities, the medical community is unbelievable, the nonprofit service sector is more broad and deep than any other in a city of our size in the country," Jones said. "If we begin to get education right, if we begin to get the integration of services right, we can do what no other city probably can do. We have a chance to be spectacular. This is what I live for."

Hubert Eugene Jones, a man who has helped shape and define the social and civic landscape of Boston for more than half a century, now at 80 years of age continues to work to make difference.