Advertisement

Judge's Quest To Find A 'Fair And Impartial' Tsarnaev Jury In Boston Finally Comes To A Close

Update 12:45 p.m.: A panel of 12 jurors and six alternates has officially been seated in the trial of Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

Our original story continues:

BOSTON — When 12 jurors and six alternates take their seats in Courtroom 9 of the John Joseph Moakley Federal Courthouse on Wednesday, their first sensations no doubt will be the weight of their assignment and the ordeal that lies before them. They are the product of an improbable, winding and wearying path of jury selection that has seemed as interminable as the winter itself.

They have been selected from a pool of 75 jurors who were chosen from a pond of 256 jurors who were chosen for individual questioning from an ocean of 1,373 jurors randomly picked and summonsed to court by Judge George O’Toole a few days into the New Year.

For O’Toole, they are an achievement, 18 “fair and impartial” jurors he was determined to find and who proved far more elusive than he first supposed. Even before they arrived at the courthouse with all the others to fill out a 26-page questionnaire with a hundred questions in early January, O’Toole had already set a date — Jan. 26 — for the start of opening statements, a display of sure confidence that soon come up against reality.

Those who passed their written examination were called back before the court for round two — a second round of questions to be individually asked by the judge and the attorneys in a process called voir dire.

Every day we who watched the proceedings became acquainted with a variety of citizens from the four corners of eastern Massachusetts: students, landscapers, software engineers, teachers, restaurant owners, a musician in Irish pubs, a processor of hamburger patties, an unemployed interior decorator and a nurse about to set out across America with her boyfriend in an RV. Some plead hardship if they were called upon to serve for a four month trial. Some worried their employers would hire someone else or drop their health insurance. Others expressed their willingness to sacrifice to fulfill a civic duty. And some perhaps appeared overly eager to be chosen.

Jan. 25, the date Judge O’Toole had scheduled for the start of opening statements, came and went. The search for a fair and impartial jury, which the defense and critics said he would not be able find in eastern Massachusetts, turned into as big a slog as the streets outside the courthouse. And as the snow piled up, the defense filed squalls of motions arguing that the slog to select jurors was evidence of a fatally flawed process that could never produce a fair and impartial jury in a city and region in which, defense lawyers argued, everyone had been the target and everyone the victims of the bombers.

The storms came and went, and so did the defense appeals, all of them denied, and with opening day at Fenway Park closer than the start of jury selection back in January, an after-hours email last week dryly announced that O’Toole’s search for jurors he deemed fair and impartial was over.

“The Court has identified a sufficient number of qualified jurors not excusable for cause to proceed to the next stage of jury empanelment, which is the parties’ exercise of peremptory challenges,” the judge said.

Translation? O’Toole had reached his goal, as he had all along insisted he would. In the face of those legal appeals to stop him, he found enough jurors — in this case 75 — to produce 12 jurors and six alternates after both the prosecution and defense were allowed to exercise “peremptory challenges” and reject as many as 23 jurors apiece without giving a reason.

Dealing With Pre-Trial Prejudice

There are three recognized methods for dealing with pre-trial prejudice, that in this case, the defense argued, was pervasive and overwhelming. One is to allow the passage of time to lower the heat of emotion and allow a more even-tempered review of events. Judge O’Toole gave one delay of two months, but denied the defense motion for more time which it argued was in line with the average time between indictment and trial in a federal death penalty case — 28 months rather than 20.

A second method is to change the venue of the trial, an extraordinary measure that was used in the case of defendant Timothy McVeigh, who was charged for the Oklahoma City bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in April 1995 in which 168 people were killed and several hundred injured. After finding that the two suspects (McVeigh and his alleged co-conspirator Terry Nichols) had been so demonized by media publicity that he could not get a fair trial in "the entire state of Oklahoma," a federal judge ordered that the trial be moved 700 miles away to Denver, where McVeigh was tried, convicted and sentenced to death.

But in the case of Tsarnaev, and in reaction to zealous advocacy and recurring motions by the defense to move the trial, Judge O’Toole insisted there was another, more suitable remedy than moving the trial. It involved rooting out those in the jury pool who were truly biased by pre-trial publicity and finding those who were not trapped by their initial opinions and attitudes. O'Toole believed, as the prosecution expressed it, that "the time tested method for determining whether a juror can actually set aside his beliefs and apply the presumption of innocence is voir dire."

In other words, if you want to know if jurors can set aside their presumption that Tsarnaev is guilty, ask them yourself.

Voir Dire

Each day for 21 days of voir dire, the judge started by addressing the day’s pool of prospective jurors. The trial might involve two-phases, he instructed them. The first phase would determine if Tsarnaev is guilty and the second phase, if the jury decided he was, would determine whether the defendant should be sentenced to death or to life without the possibility of parole. “The jury is never required to find that a sentence of death is justified,” O'Toole told them. But “the jury and not the judge is responsible for determining if a defendant sentenced to a capital crime should live or die."

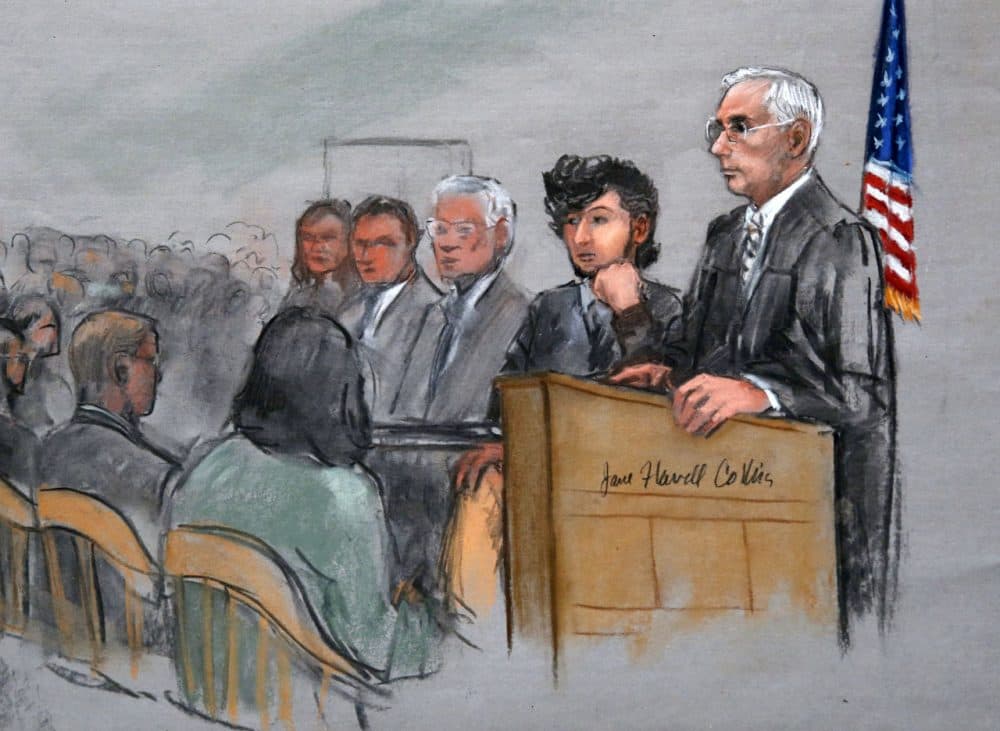

Following those remarks, O’Toole would have the jurors sworn in by his clerk. They would leave the courtroom in a group, then each one would be called back individually for questioning. The prospective juror took a seat at the end of a table, next to the judge, and faced seven or more attorneys along with the defendant, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who seemed to take little interest in the proceedings.

But for all the drama of that question and the answers given or attempted by the prospective jurors in sometimes protracted back and forth, the critical issue in the voir dire for Tsarnaev, and the one at the heart of his motions to move the trial, was whether the people who might decide his fate could be fair and impartial, even when they said they could.

That line of questioning began with the judge, who presided over the questioning and allowed limited questioning from the prosecution and defense. O’Toole asked each potential juror if he or she had formed an opinion of Tsarnaev’s guilt or innocence. Many of them responded that indeed they had, and invariably they presumed Tsarnaev was guilty. Asked how they came to that opinion, they said they had seen, heard or read coverage in the media.

But presumption of guilt did not automatically disqualify jurors from consideration, at least not at the outset, Judge O’Toole stated. He could cite the Supreme Court, as the prosecution did, when quoting a finding that “it is a premise of [our] system that jurors will set aside their preconceptions when they enter the courtroom and decide cases based on the evidence presented.”

In each and every exchange, O’Toole informed the juror that the law requires jurors to set aside their opinions before hearing the evidence at trial. Then he asked this critical question: “Can you set aside your opinion?” Or as he put it to one woman: “Would you be able to discipline your mind so you can make a decision based on evidence presented at trial rather than ideas you came in with?”

Both the nature of the questions and who was asking them came under criticism from members of the Bar and even a recently retired federal judge in Boston. Who wants to give an answer “No, I can’t discipline my mind” or “I can’t be fair"? When the question is posed by a man who dresses in black robes and whose presence commands people to stand whenever he enters or leaves the courtroom, people would more likely tailor their answers to please, noted that former judge, Nancy Gertner. “When you put the question that way,” she said, “is there really any wonder people say ‘Yeah, I can do that.'”

Even when jurors answered that they did not think they could set aside their presumption of guilt, the judge would often remind them that the law requires jurors to set aside their opinions before hearing the evidence. And then he would ask again.

Joshua Dubin, a criminal defense attorney in New York and a noted jury consultant in high-profile cases across the country, called this nothing short of browbeating.

“The message with additional probing and questioning is that it is not OK to feel that way. You’re doing something wrong," Dubin said. "I have yet to understand why judges think they can browbeat people out of a bias. The presumption is supposed to be of innocence. The judge’s job and the prosecutor’s job is not to rehabilitate jurors. It is to excuse them.”

As soon as the jurors revealed their presumption at the outset that Tsarnaev was guilty, Dubin says, they should have been disqualified.

“End of story. It should end there. The presumption is supposed to be of innocence,” Dubin said.

The Pool

A mother from Mansfield, juror number 70, a homemaker with two degrees in psychology, who called herself “a little opinionated” offered her own insight to O’Toole. “We ask jurors to follow the law,” he began, and then asked if she could put her opinions to the side and come in with an open mind. “I think it’s hard,” she replied both pleasantly and pointedly.

“If you have a belief in your head, if you’ve heard so much about something, you start to believe that it’s true," she said. "It’s hard to set that aside. I can try to, but I can’t say that wouldn’t influence my thinking at all. I don’t know if the brain works that way.”

Juror 70 says media coverage of the case leads her to believe that #Tsarnaev is guilty. Judge now asking if that will affect her judgment— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 20, 2015

Juror 70 says it would be difficult to set that belief aside. Says she would try, but can't say it won't influence her thinking. #Tsarnaev— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 20, 2015

Critics citing research into human behavior say the brain doesn’t work that way, and that voir dire shouldn’t be conducted with the judge asking most of the questions while keeping the attorneys to narrow limits.

“Our values, beliefs, life experiences and ultimately our opinions are what they are," Dubin said. "You cannot ask someone if they can put aside their opinion. Where are they going to put it? Into a secret box in their brain?”

Yet for all the assertions and fault-finding by critics, a number of people did tell the court they in fact could not be fair, that indeed they were biased against Tsarnaev.

“I don’t think I could sway my judgment,” said juror number 62, who on a scale of one to 10 in favor of the death penalty put himself at 10. “It would take an awful, awful lot.” And with that answer, he was allowed to leave.

Juror 62 says he believes in death penalty "strongly." Put down a 10 on a scale of 1-10 indicating support. #Tsarnaev— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 20, 2015

Juror 62's wife was at the Pru when the bombs went off. He had to go there to pick her up. #Tsarnaev— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 20, 2015

Others, a number of them software engineers, insisted that they were able, and trained, to distance themselves from media coverage and emotion. “I would base everything on evidence, what the witnesses would say,” said juror 11, a young man with more than a touch of defiance. “I don’t get swayed by the media. I don’t get swayed by anybody.”

Juror 11 said in response to death penalty question: "justice is justice." Says he has almost no reservations about death penalty. #Tsarnaev— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 15, 2015

Juror 98, a senior software engineer with a degree from MIT, said he went along with popular opinion in the media that “said the defendant is guilty ... [but] I understand as an engineer the need for logic and facts,” which meant when it came to putting aside his presumption of guilt, “logically I can do that or believe I can.”

Juror 98, answered on questionnaire that he believes #Tsarnaev is guilty and should be executed.— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 21, 2015

But, Juror 98 says he could set those preconceived notions aside if seated.— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 21, 2015

Then came another researcher and a social scientist, juror 42, who matter-of-factly stated “I look at the evidence.”

Juror 42 says that he would be able to assess the evidence and question assumptions since he is a scientist and researcher.— WBUR Live (@wburLive) January 16, 2015

It was a perfect answer for the proceedings. Answers like that enabled O’Toole to state in written opinions and in casual courtroom remarks to state that voir dire was working and “there is no reason to halt a process that is doing what it is intended to do.”

Invariably the most dramatic of the exchanges with jurors involved their attitude and opinion about the death penalty. Since federal prosecutors seeking the death penalty for someone convicted of capital crimes — and Tsarnaev is charged with 17 capital crimes — can never obtain it from jurors who say they would never impose it, the Supreme Court has upheld the rule that people with such absolute conviction cannot sit on the jury; they are disqualified as unfit to serve on a “death-qualified” jury.

So the climactic moment of each exchange inevitably involved one closing question from prosecution. It generally came from Assistant U.S. Attorney Steven Mellin, and it came down to something like this: When and if the time came and the juror thought the evidence supported the imposition of the death penalty, would the juror balk? Or as Mellin put the question, in four words: “Could you do it?” Answer no and you were off the jury.

As the search for a pool of 75 jurors ground forward, O’Toole wrote that his success at finding jurors whom he deemed “fair and impartial” proved there was no need to move the trial. To which the Tsarnaev’s lawyers and criminal defense attorneys outside the case complained that declaring jurors to be fair and impartial does not make them so.

A Cloud Of Legal Controversy

Of the three ways to lessen the effect of pre-trial prejudice, delaying the trial is one, and O’Toole had allowed the defense only two additional months. Moving the trial is another, and O’Toole denied it. And a voir dire in which lawyers are given wide latitude in questioning prospective jurors is the third.

Ideally, voir dire is a search for the truth — it’s supposed to get people to tell you how they really feel. And in rejecting three motions to move the trial out of Boston, O’Toole stated his foundational belief in the power of voir dire to find a fair and impartial jury. He characterized the jury questioning as searching and thorough. But here too the defense said it was thwarted by O’Toole, prevented every time from asking jurors what it was they heard or saw or read that made them presume Tsarnaev was guilty.

Even as the judge continued jury selection — despite defense attempts to suspend the proceedings — Tsarnaev’s lawyers filed still a third motion with the judge to move the trial and a second petition with the a federal appeals court for a “writ of mandamus," an order from the appellate judges to O’Toole to move the trial elsewhere. That was asking for extraordinary action in what the defense called an extraordinary case.

The grounds the defense gave for its repeated motions and petitions were emerging facts from its analysis of the initial juror questionnaires filled out by those 1,373 people summonsed at the beginning of January. Sixty-eight percent of them said they presumed that Tsarnaev was guilty and 69 percent had a self-identified connection to “people, places and or events” in the case through allegiance or personal relationships.

From those questionnaires the defense excerpted written attitudes and opinions that they said supported their contention of pervasive prejudice, though the prosecution insisted they were wholly unrepresentative and chosen for their inflammatory value.

"He does not deserve a trial," wrote one prospective juror. "[T]hey shouldn't waste the bulits [sic] or poison," read another. "Hang them." On a parallel note, another juror wrote: "We all know he's guilty so quit wasting everyone's time with a jury and string him up." Someone else quoted advice from his co-workers: "they basically said 'fry him.'"

The defense argued that it was not only the unrelenting media publicity that created the prejudice, but something deeper. It cited the government itself in characterizing the bombing as an attack on the entire community: Boston, the marathon, all of eastern Massachusetts. Citizens had been told by authorities to “shelter in place” and some residents of Watertown were forced out of their homes by squads of armed police responding to a terrorist attack.

But higher courts have always been reluctant to interfere with the decisions of trial judges in selecting juries. And in a split-decision announced late Friday night on the last day of February, the three judge panel of the appeals court denied a second attempt by the defense to get the court to move the trial.

Back at the beginning of February, when he rejected the third motion for him to move the trial, Judge O’Toole had cited a Supreme Court ruling called Skilling (after Jeffrey Skilling, the former CEO charged with fraud and insider trading at the scandalously failed Enron Corporation headquartered in Houston.) It upheld the decision of the judge who denied him a change of venue away from Houston.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court pointed to a potential jury pool of 4.5 million people in the Houston area and said the suggestion that 12 impartial individuals could not be found was “hard to sustain.”

In O’Toole’s opinion, the judge noted that “it stretches the imagination” for Tsarnaev’s attorneys to argue he could not find 12 impartial jurors from about the same number of people who live in eastern Massachusetts as live in the Houston area.

Late Friday night, in closing the door on the defense for perhaps the last time, the majority of two appellate judges said their decision was based on narrow legal grounds: they did not have the authority to order O’Toole to move the trial. Tsarnaev had not shown that he faced irreparable harm since there was no jury, no trial and no conviction yet. Still, they went out of their way to take on the defense claim that “every potential juror in [eastern Massachusetts] is automatically disqualified.”

With arch words they wrote: “That alone is a remarkable assumption about five million people ... and one much to be doubted.”

The sole dissenting judge, Juan Torruella, who has been on the federal bench for over 40 years, had railed against his associates in an earlier ruling. Now he added these stinging words for his colleagues on the appeals court.

“It is absurd to suggest that Tsarnaev will receive a fair and impartial trial in the Eastern Division of the District of Massachusetts ... no amount of voir dire can overcome this pervasive prejudice, no matter how carefully it is conducted,” he wrote.

Torruella’s words ended the week as well as the opinion. They were not going to stop the formation of a jury or the trial from going forward in Boston, even as the defense filed a fourth motion with Judge O'Toole to move the trial. But on the eve of opening arguments, Torruella’s dissent billows the cloud of controversy that may hang over the trial for years to come.

This article was originally published on March 03, 2015.