Advertisement

Analysis: 'SEC Primary'? More Like March Madness

On March 1, 13 states hold their Republican primary contests. Under party rules, March 1 is the first possible day states other than Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada are allowed to hold their primaries. This delegate bonanza contest has been dubbed the “SEC Primary,” after the six states that vote that day and are home to colleges from the Southeastern Conference.

Catchy as the name is, it’s not a good fit, for two reasons. First, it understates the considerable influence of the non-SEC states voting that same day. Second, winning the “SEC states” voting on March 1 has not meant that much during the last few nomination cycles.

Let’s take the second point first. The SEC is good at some things. As a Big-10 alum, it pains me to stipulate that the SEC seems to be pretty good at football lately. With the Alabama Football Factory set to contend for its roughly 247th national championship Monday, I can’t deny there seems to be some good teams in the SEC. But when it comes to predicting who will win the Republican nomination, the SEC states’ record is spotty of late.

In 2012, three of the six March 1 SEC states voted for Rick Santorum, and one went to Newt Gingrich. Just two (Arkansas and Texas) went to the eventual nominee, Mitt Romney. In 2008, Mike Huckabee won four of the six, leaving eventual nominee John McCain with wins in Texas and Oklahoma. This year, we may again see moderates struggle in the South and lose to more conservative competitors. And once again, it could turn out that this may have little bearing on the final nominee. In some ways, the SEC states are behaving more like Big-10 Iowa in this regard: highly prized, but not predictive of the ultimate winner.

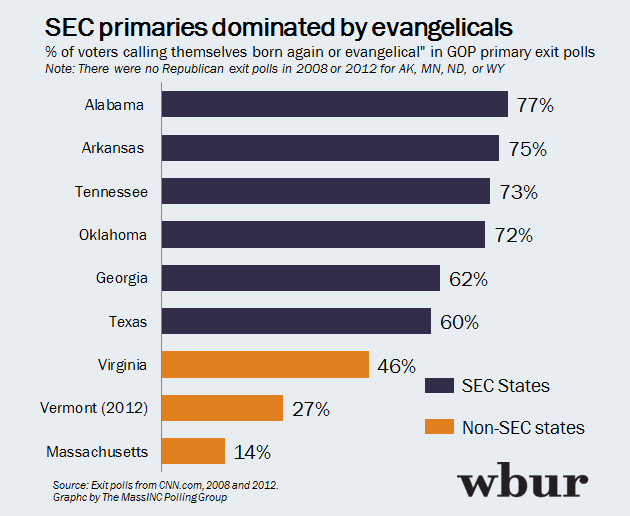

Meanwhile, there are seven non-SEC states voting or caucusing the same day: Alaska, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, Virginia and Wyoming. Together, these account for around a third of all delegates up for grabs on March 1. The voters in many of these states are more moderate than those in the SEC where, according to exit polls, an average of 66 percent attend church weekly, 70 percent are evangelical, and 71 percent call themselves conservatives. In the case of the Northeast primary states of Massachusetts and Vermont, the electorates are dramatically different, and likely friendly to a different type of candidate. While exit polls are not available for all of the states that vote on March 1, their voting records in recent elections point to far more moderate electorates than will show up in the SEC states.

The SEC states also have minimum thresholds of 15 to 20 percent to receive any delegates. Unless a candidate is planning a serious effort in the South, there is no payoff for just showing up. In other words, the moderate lane to the GOP nomination pretty much detours around the South. Moderates have a better shot of clearing the lower minimum bars and winning over more receptive voters in the non-SEC states voting on March 1.

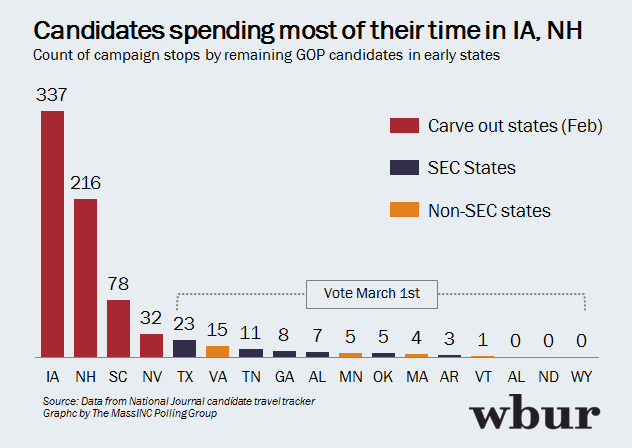

All of these factors suggest conservative and moderates candidates should pursue differing strategies heading into March 1. But with a couple of exceptions, the campaigns don’t seem to have given much if any thought beyond the first few primaries. In the last three months, the remaining GOP candidates have made a combined total of 497 campaign stops in New Hampshire, compared to just 86 stops in all the March 1 states put together.

The media seem to be suffering from tunnel vision as well. Commentators were stumped when Donald Trump left the very well-trodden paths of Iowa and New Hampshire last week to make only the second visit to Vermont by any GOP candidate. Vermont doesn’t have a lot of delegates at stake. In fact, it’s tied with Delaware for the fewest of any GOP contest. But Vermont votes on March 1, as does Massachusetts, where Trump has also held rallies. More than any candidate, Trump seems to understand the value of looking ahead to all the states voting on March 1, especially when two of those states border New Hampshire.

So rather than the “SEC Primary,” let’s call March 1 what it is: the beginning of a month of March madness.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly reported one of the state primary results for the 2012 Republican race. We regret the error.

Steve Koczela is president of the MassINC Polling Group and a regular contributor to WBUR Politicker.

This article was originally published on January 11, 2016.