Advertisement

When Homer Freed Harold: Justice For The Innocent, And A Friendship Forged

Resume

This story was done in partnership with reporter Ken Armstrong at The Marshall Project.

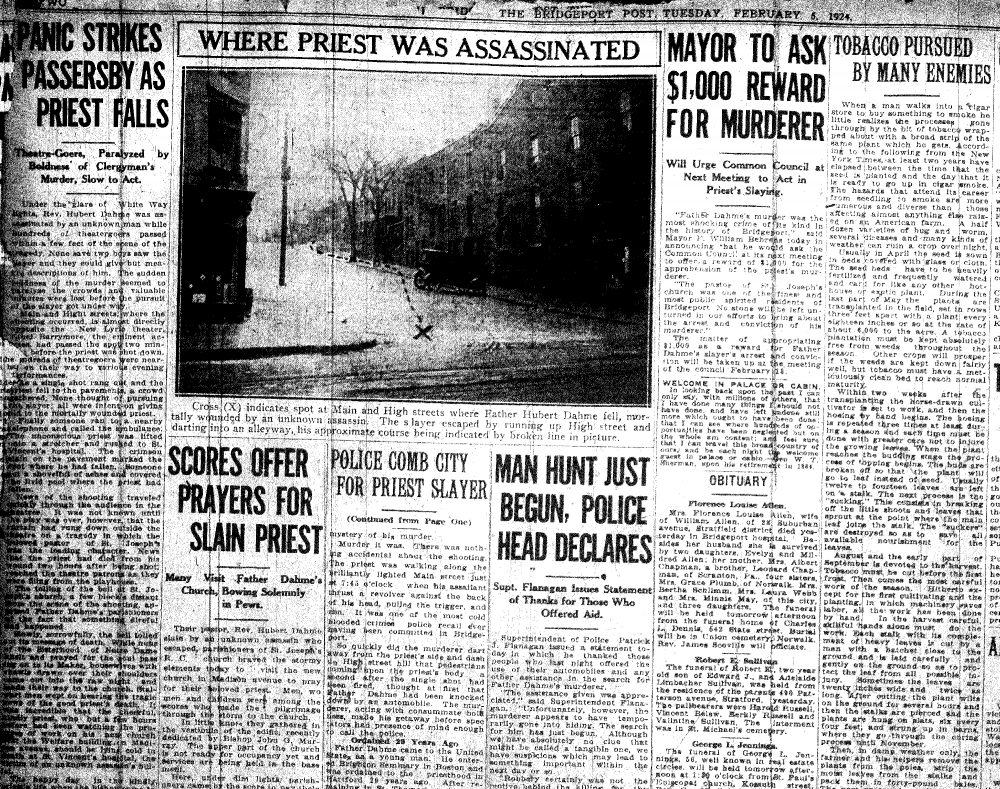

On the night of Feb. 4, 1924, downtown Bridgeport, Connecticut, bustled. People braved the winter chill to enjoy dinner out, or to take in a show at one of the grand theaters. At 7:45, actress Ethel Barrymore was about to take the stage at the New Lyric Theater. Buster Keaton was performing a few streets over.

Meanwhile, a real-life drama was about to play out in Bridgeport — one that would shake the city to its core.

It began mundanely.

A Catholic priest stepped out for his nightly stroll. He was 56-year-old Hubert Dahme. He was born in Germany, went to seminary in Boston, and had become a beloved fixture in Bridgeport since he took the post of pastor at St. Joseph's Church 23 years earlier.

As Father Dahme walked along Main Street, a man approached him from behind. The man pointed a revolver by Dahme's ear and fired a single shot. The gunman fled as Dahme fell face down on the pavement. The priest died that night, as fellow priests chanted the litany of the dead in the hospital halls.

Bridgeport Police came under intense pressure from the public and press to find the killer of the priest — a clergyman who, according to a Bridgeport Times headline, led a "placid, blameless life; hated none and aided many."

The newspaper quoted the city's mayor, William Behrens, announcing plans to offer a $1,000 reward for information leading to the gunman's arrest and conviction:

This repulsive crime instills fear in the hearts of every citizen, and I am determined that the murderer shall not escape the clutches of the law. Every force at the command of the municipality shall be thrown into the hunt for Father Dahme's slayer.

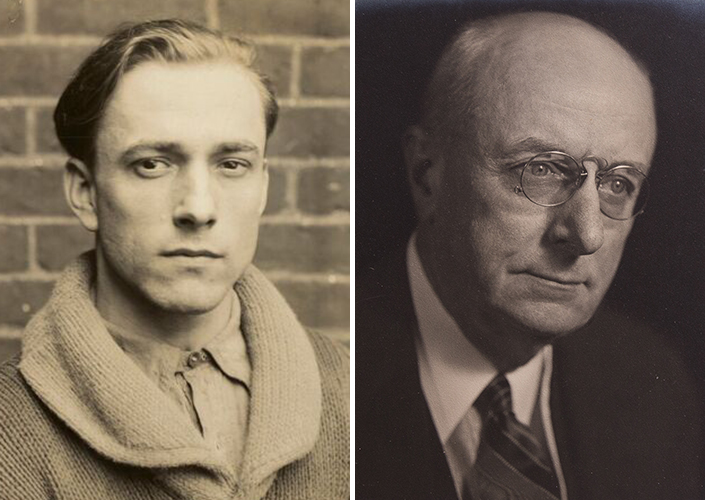

One week after the murder, an officer in a nearby town noticed a young man he thought was acting strangely. The man was Harold Israel from rural Pottsville, Pennsylvania. He was a wispy 20-year old — barely over 5 feet tall. He'd been honorably discharged from the Army a few months before.

Israel had been staying in a Bridgeport boarding house, where he went to meet up with some Army buddies. He didn't own much, but he did have a gun on him. It had five chambers. Four of them were loaded; one bullet had been fired.

Police booked Israel on gun charges. Then Bridgeport cops interrogated him about the murder of Father Dahme. Israel insisted he had nothing to do with the crime. But after 28 hours of intense questioning, he confessed. He was charged with first-degree murder — a crime punishable by hanging. The young veteran became public enemy No. 1.

An inquest determined that the evidence, indeed, pointed to Israel. The police investigation had turned up people who witnessed the shooting and some who saw the gunman run away. They described the shooter's dark overcoat with velvet collar and his gray cap. That sounded similar to Israel's clothes.

Some of the witnesses identified Israel as the killer when police brought him to the station. And a ballistics engineer told police the bullet that killed the priest came from Israel's revolver.

The evidence was presented to the chief prosecutor, Fairfield County State's Attorney Homer Cummings. Cummings, 54, was a man of great prominence. He'd been mayor of Stamford, Connecticut, three times, and he'd served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee. He was an imposing man — 6-foot-2. He was Ivy League-educated, having completed his undergraduate and law degrees at Yale.

'It Seemed Like A ... Perfect Case'

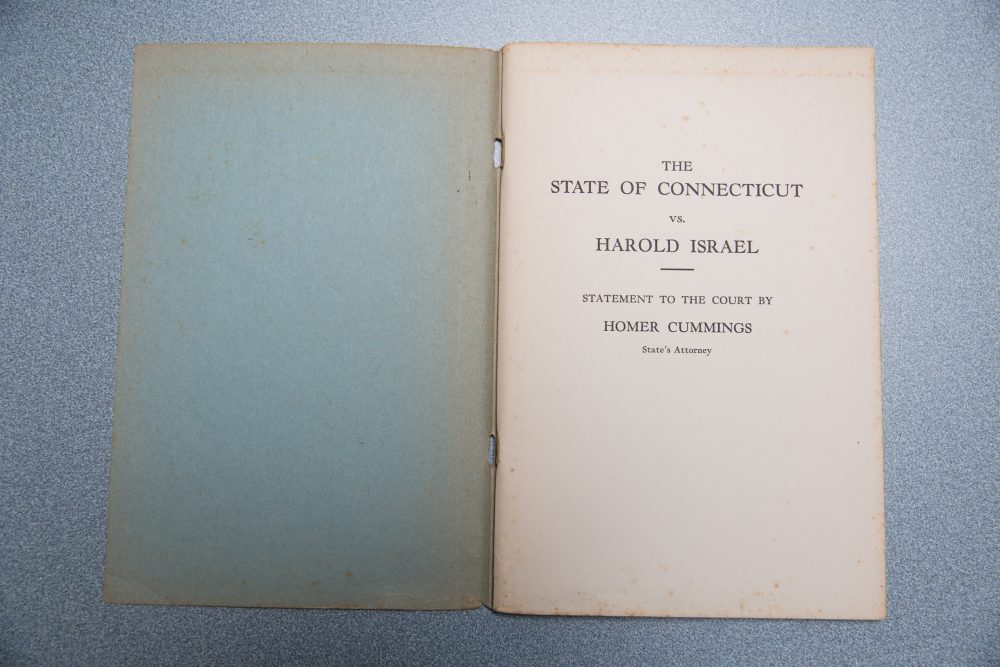

On May 27, more than three months after Father Dahme was murdered, there was a pretrial hearing. Prosecutor Cummings stood before the judge and spoke for about 90 minutes without any notes:

The case against the accused seemed overwhelming. Upon its face, at least, it seemed like a well-nigh perfect case...

But maybe it wasn't the perfect case.

Some people had wondered if Israel was a victim of circumstance. Cummings told the judge he had felt there were "sufficient circumstances of an unusual character involved to make it highly important that every fact should be scrutinized with the utmost care and in the most impartial manner."

So that's what Cummings had done. He had conducted his own detailed investigation.

And that day in court, Cummings — the lawyer charged with prosecuting the case — methodically addressed each scrap of evidence and then tore it to shreds.

Cummings had gone to the scene of the crime in the dark of night. He had concluded that the people who saw the killer could not have identified the gunman running away in such dim light.

What's more, Cummings had hired six ballistics experts. They all told him that the bullet that killed Father Dahme could not have come from the gun found on Israel. The markings on the bullet didn't match up.

As for the fact that Israel had confessed to the crime, doctors who'd examined him claimed the police interrogation left the young suspect too exhausted to say anything reliable — that he only wanted to get some sleep. In fact, once Israel did get rest, he again insisted he was innocent.

And that's what Cummings concluded: Harold Israel was not the killer. The prosecutor told the court:

It is just as important for a state's attorney to use the great powers of his office to protect the innocent as it is to convict the guilty.

Cummings entered a nolle prosequi. That's a Latin term for the decision to no longer prosecute, or no longer pursue. The judge agreed and ordered the case against Israel dropped.

Cummings was celebrated in the press and in legal circles. Harvard Law School professor and future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter later told Cummings his actions would "live in the annals as a standard by which other prosecutors [would] be judged." The court remarks of Cummings and the judge are transcribed in a 28-page booklet and have been published in law journals.

'Your Friend'

Israel wasn't in court the day his life was spared. When he was told he'd be set free, he said, "That's good. It came out right."

The former murder suspect and Army vet headed home to Pennsylvania to find a job. Meanwhile, Cummings' star kept rising. In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt named Cummings U.S. attorney general. Cummings built up the FBI and fought organized crime. He is credited with the creation of Alcatraz, the federal penitentiary in San Francisco Bay.

When he retired from the government, Cummings went back to practice law at the two firms he had founded, in Stamford and Washington, D.C.

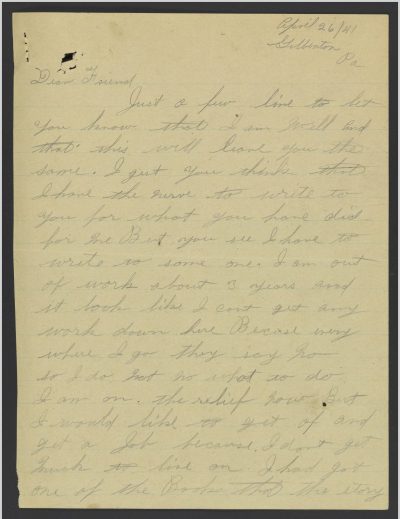

A couple of years went by. Then the former prosecutor received a letter from someone he likely thought he'd never encounter again — the man he'd saved from the gallows, Harold Israel:

Dear Friend: Just a few line to let you know that I am well and that this will leave you the same. I guess you think that I have the nerve to write to you for what you have did for me. But you see I have to write to some one. I am out of work about 3 years and it looks like I can't get any work down here because everywhere I go they say No so I do not know what to do.

He signed it: "Your friend, Harold Israel."

Cummings wrote back within a week. He was kind, but said he wasn't sure how he could help:

... was very glad, indeed, to hear from you. I do not know at present what I can do with reference to the matter you mention but I shall certainly be glad to do anything I can.

'Boomerang' — And A Payday

Five more years passed, then Cummings got another surprise: Hollywood came calling.

20th Century Fox was beginning work on a movie based on the Cummings-Israel court case. It would come to be called "Boomerang." The filmmakers wanted to know where Israel had ended up. So Cummings asked his former federal colleague, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, to investigate.

Hoover reported back: Israel, the onetime murder suspect, was a family man, hard worker and trustee at his church in the village of Gilberton, Pennsylvania.

Cummings welcomed the news. And he decided to go even further, getting involved with the movie production. He reviewed the script and urged the filmmakers to depict Israel as a respectable man, not as a "penniless tramp," as the former defendant had been portrayed in a magazine article that led to the film.

But that wasn't all. Cummings negotiated with the movie producers to pay Israel $18,000 for the rights to his story. That would be about $220,000 today — a nice take for a coal worker raising a family in a small town.

'He Worships You'

Gilberton was a company town. A coal company owned most of the land in the village. Israel worked in the coal yard seven days a week for a sum of $60. He lived in a simple duplex on an unpaved road.

Some of Israel's descendants still live nearby. We went to Gilberton to meet them at the home of Israel's granddaughter, Darlene Freil. We brought along something we knew the Israel descendants would want to see: transcripts of letters that had gone back and forth from their family in Pennsylvania to the grand home of attorney Cummings. The letters are housed in an archive of Cummings' papers at the University of Virginia.

The Israel grandkids knew the letters existed; their grandmother had a big drawer full of them. But they'd never read them. The family sat around Freil's kitchen table to look at the transcripts.

The first letter was written by their grandmother, Olive Israel — Harold's wife. She had written to Cummings to thank him for securing the money for Harold from the film "Boomerang." The letter reads, in part:

We can't begin to thank you enough for what you have done for us... I keep asking my husband "Are you sure it is true." He just laughs at me and says "Sure it is."... To him Mr. Cummings you are next to God. He worships you. He said he would trust you more than anybody in this world.

As Lisa Berrier read the letter out loud, her voice cracked and tears welled in her eyes.

"Typical of my Gram. That's why I started crying," Berrier said.

She and the rest of the Israel family have always known about their grandfather's brush with the law. But they heard about it from his wife — their grandmother Olive — not from him.

"It was always Gram. [Harold] never talked about that," Freil said. "I think that was one part of his life that he didn't want to dwell on or think of. He just wanted to get on with his life and enjoy his family and everything."

As the years went by, there were many more letters between Olive Israel and Homer Cummings — 10 years' worth. Olive often asked the former prosecutor for advice. In one letter, she wondered if she and Harold were spending the movie payout too lavishly. They'd bought a used Chevy, were each planning to get a new set of teeth, and wanted to put a bathroom inside the house. Olive wrote:

I think every house should have a bathroom. We have to wait for the bathroom fixtures, tub, etc. as they are very hard to get. But I hope we can soon get them as it would be much more convenient with a bathroom... So Mr. Cummings I don't think it is extravagant to try to buy these things that we wanted all our life and could never get until you made it possible, do you?

She added a P.S.:

We got a frame for your picture and have it sitting on our fireplace. The fireplace isn't a real one, tho. Just an imitation.

Cummings wrote her back:

I note also the description of the expenditures you are making, and it seems to me that they are entirely justified. I hope that you and your family will derive great comfort and happiness from these expenditures.

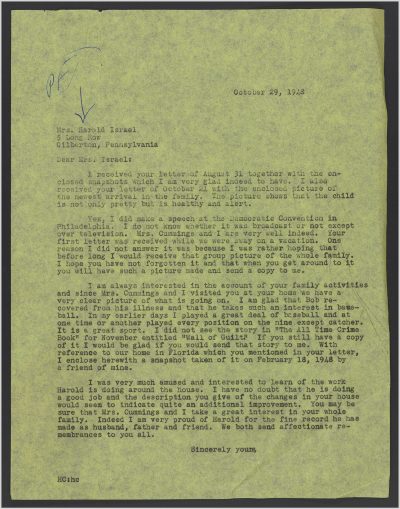

The correspondence continued. These are excerpts of some of the letters, including one of the few Cummings directed to Harold specifically:

Olive to Cummings:

We have built an extra room on our home... We use our home a good deal. The boys love to read funny books and play records so this room will be used real hard. Someday I hope you can come and visit us when we get all fixed up. I guess your house is beautiful...

Cummings to Harold:

Enclosed you will find a few clippings relative to the "Boomerang." From all I can learn, the critics have given very favorable reviews. I myself saw the picture and it certainly makes quite an exciting story... By the way, if any newspaper people or others make any attempt to interview you or members of your family I would suggest it would be best not to make any statements of any kind... I suggest that you refer them to me.

Cummings to Olive:

I am always interested in the account of your family activities and since Mrs. Cummings and I visited you at your home we have a very clear picture of what is going on... Indeed I am very proud of Harold for the fine record he has made as husband, father, and friend.

Gifts, And A Visit To Coal Country

Cummings had a small family. He'd married four times. He became a widower twice and divorced twice. He had just one grandson. But the dynamics of divorce kept the Cummings family members distant.

Meanwhile, Cummings' relationship with the Israels grew warmer. He sent gifts to the Israel home in Pennsylvania, including pearls and perfumes for Olive, ornate lamps, and baby clothes his wife knit for the Israel grandchildren. Cummings, the Washington socialite, even brought his wife to visit the Israels at their home in coal country. Olive wanted so much to impress them, she dyed the hair of the pet terrier so it wouldn't look gray.

You are getting together quite a family, and I hope that happiness and content follow you all the days of your life.

Cummings wrote that to Olive in October 1949. The Israel family is grateful to Cummings to this day — first for his courage in the courtroom and then for his kindness. Olive Israel used to remind her grandchildren that they wouldn't be here if the prosecutor hadn't done what he did: eviscerate the prosecution's own case and exonerate their grandfather.

"Cummings had a good heart for how he treated my grandfather and tried to protect him," said Harold's granddaughter, Darlene Freil, during our visit.

Cummings wrote his last letter to the Israels in 1956. Two months later, he died, at age 86.

There's a list of dozens of people who sent flowers to the Cummings funeral. Among them: a Supreme Court justice, a college president and an ambassador.

Also on the list: Mr. and Mrs. Harold Israel of Gilberton, Pennsylvania — a final thank-you from the onetime murder defendant to the former prosecutor who saved his life.

Harold died eight years later of black lung disease — the scourge of the coal worker. He was 60 years old.

The man who murdered Father Dahme in Bridgeport in 1924 was never caught. Connecticut authorities today say that's a tragedy, but not as great a tragedy as convicting the wrong man.

-- Read The Marshall Project story, "Homer and Harold: An Extraordinary Story of Justice Done, and What Came After," here, and via Smithsonian magazine.

-- For more on Homer and Harold, listen to these stories (photos by Ryan Caron King for WBUR):

This segment aired on December 20, 2016.