Advertisement

Speedy Ortiz On The Brink Of Stardom: A Look At How The Boston Band Got There

“I’m in Austin and I will play drums in your band tomorrow between 12-5pm,” the comedian Hannibal Buress tweeted on March 17. “I can’t play drums. It’ll be bad.”

“Hey @hannibalburess yr cordially invited to drum with speedy ortiz at the @pitchfork showcase,” responded Sadie Dupuis, the lead singer of Massachusetts indie rock band Speedy Ortiz. “Or we could get pizza.”

Lo and behold, the next day there Buress was at South by Southwest, the annual music festival in Austin, Texas, looking mildly astonished as he swapped places with drummer Mike Falcone for the song “MKVI.” “Thanks for letting me ruin your last song,” said Buress, eyebrows raised behind black sunglasses. “If you f--k it up we’re not going to get discovered this year,” Dupuis replied wryly. The sun beat down on a crowd still sleepy in the heat of midday. Dupuis played it cool onstage, but in a photo with Buress after the set she looks disarmingly starstruck.

Buress wasn’t lying—he was very bad—but the video buzzed around the Internet, popping up on Pitchfork, Slate and The AV Club. The next day in an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live, Buress blanked on Speedy Ortiz’s name. It was a strange, exhilarating episode, and seemed to encapsulate the band’s current moment, poised as they are on the brink of a breakthrough: brushing shoulders with fame, but not yet on the tip of the tongue.

“It is kind of a funny spot to be in,” says Falcone. “Because it just kind of seems like everything is wide open at the moment and anything can happen. So it’s kind of an exciting point.”

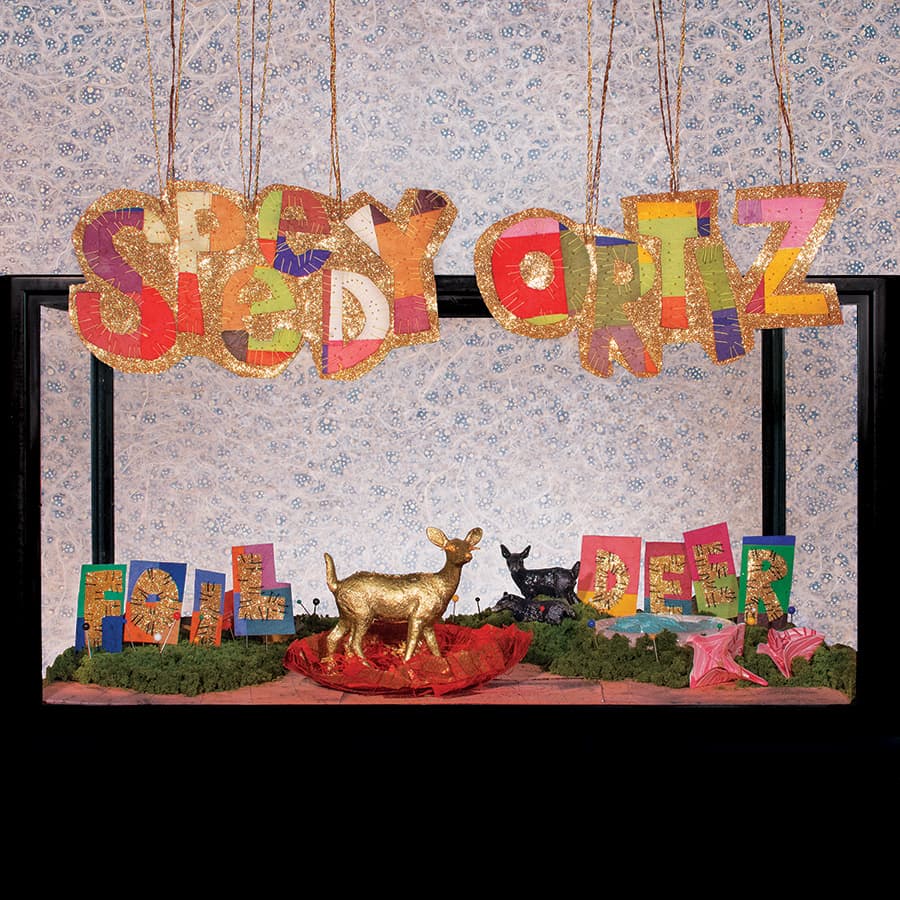

(Preview songs from "Foil Deer" here.)

Speedy Ortiz had premiered the first single off of their sophomore studio album “Foil Deer” on Feb. 10. The song, “Raising the Skate,” opens with an electric guitar’s lone tremolo. It is joined presently by another note, lower in pitch, and for a moment the two vibrate agreeably, a familiar preamble to the roaring pleasure of rock ‘n’ roll’s inevitable assault. The entrance of a third voice, high and metallic, knocks the triad sideways into an ominous dissonance. By the time the rest of the band slams in, just seven seconds into the song, we have already been handily treated to Speedy Ortiz’s patented concoction of decisiveness and tingling sonic discomfort.

Speedy Ortiz’s singular sound—wittily unharmonious and defiantly verbose—is shaped in large part by the band’s frontwoman and sole songwriter, Sadie Dupuis. In the most obvious ways, “Raising the Skate” is a quintessential Dupuis composition. She is the sort of writer who on occasion prompts the consultation of a dictionary, and in the very first line of “Raising the Skate,” she casually tosses off the term “hypnic jerk,” a reference to the lurching falling sensation that may strike in the final moments before sleep. The phrase neatly encapsulates what Speedy Ortiz is about: Dupuis’s offbeat harmonic sensibility and impressive vocabulary periodically wrest our attention from us, lest we drift off into passive complacency.

At the same time, “Raising the Skate” displays a newfound directness. When Dupuis hits the first chorus, she unleashes a dictum of sorts. “I’m not/ Bossy, I’m the boss/ Shooter, not the shot,” she declares, voice rising amidst a noisy, staggering tumult.

Advertisement

“It’s sort of an album about cutting out bullsh-t and taking care of yourself,” says Dupuis. “And maybe in that sense it’s more clear and direct because I’m not trying to hide these conflicts under a lot of metaphor.”

As she says this it is mid-March, a little over a month before the April 21 release of “Foil Deer” and Speedy Ortiz’s April 22 show at the Sinclair in Cambridge. The press has just begun to hit, and will snowball thrillingly in the coming weeks: a write-up in The New York Times, an exclusive review on NPR Music’s “First Listen.” Stereogum put the band’s single “Puffer” at the top of their list of “The 5 Best Songs of the Week.” Rolling Stone praised Dupuis’s “ornate vocals and elaborate storytelling.”

I am sitting with Dupuis at a cafe in Boston’s Allston neighborhood not far from her apartment. She wears a gray sweater tied at her midriff, black acid wash jeans, and bright blue sneakers. Dupuis is slight, and tends to hold herself coiled up, contained; but she has a blazing, direct gaze, her eyes the kind of green that ought to be impossible without an Instagram filter. She is a fast, hyper-articulate talker with an arch sense of humor that emerges in imaginative asides, like the one she provides about her mother’s home in rural Connecticut: “If, God forbid, Jason Voorhees shows up there, no one’s going to know for weeks because it’s this really spooky woods with bears and coyotes and sh-t.”

Speedy Ortiz’s last album, “Major Arcana,” spent a good deal of time mired in the breakdown of love and relationships. Dupuis says that at some point, she got tired of singing about her exes. She describes struggling to extricate herself from an “emotionally abusive” relationship prior to writing the songs on “Foil Deer.”

“It was this horrible relationship that made me not want to do anything and I couldn’t get out of it,” she says. “And then I did. And I was like, ‘Wow, this is amazing. Let me not write a whole album of angry songs about what this person has done to me.’ Because I think sh-tty people don’t deserve songs about them anymore.”

Yet “Raising the Skate”—and by extension “Foil Deer”—is more than just a personal statement, or even a repudiation of singer-songwriter cliché. It is a self-conscious engagement with a bubbling feminist dialogue about the “soft” sexism so often encountered by women in the workplace. The issue was in the news again recently thanks to a high-profile lawsuit filed by interim Reddit CEO Ellen Pao after she was fired by the venture capitalist firm Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield and Byers; in the view of many feminists, Pao lost because the Silicon Valley boy’s-club culture is too insidious, too difficult to prove in court. Similarly, in a revealing interview in Pitchfork, Bjork recently brought nuanced insight to the sometimes subtle manifestations of sexism in the cultural conversation around female artistry.

Dupuis nods appreciatively when I bring up the Bjork interview. She says that she relates especially to Bjork’s description of how, so often, “producers [take] credit and the women have to be invisible. And it’s certainly something that I’ve felt, and it prompted the writing of [‘Raising the Skate’]. I feel like a lot of people have come out recently with interviews along those lines. [New York singer-songwriter] Mitski has said similar things about working with producers, and she has self-produced a lot of what she works on.”

“I feel like women, more often than men, in interviews are asked, ‘So do you write all the songs? Or is someone else writing them for you?’ I’m like, no, I f--king write the songs.”

Dupuis grew up in New York City, splitting her time between her mother’s place on the Upper East Side and her father’s in Greenwich Village. They divorced when the 26-year-old was little, and Dupuis, an only child, does not remember them together. Her parents were well-connected in New York’s underground rock scene, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Lydia Lunch and The New York Dolls, and both held jobs in the music industry; among other things, her father was one of the founders of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

As a child, Dupuis remembers her parents’ rock ‘n’ roll exploits being mostly behind them; her father worked for many years in finance and for his family’s insurance brokerage firm. As a child, Dupuis remembers her mother, a portrait and landscape painter, taking her to galleries and museums. Her father, who died of cancer in February, brought her to concerts—usually bands of her choice, like Hanson and No Doubt, but Dupuis remembers seeing Sonic Youth, too.

“When my dad was sick, I went down to New York all the time to hang out with him,” says Dupuis. “And he was clearly panicking because he thought he had a little more time left than he did, but he was trying to tell me his entire life story. And there are so many f--king crazy stories about—he has some story about a tiger in Plexiglas at a Grace Jones show, he had to wrangle the tiger because it escaped. And some crazy stories about Keith Richards in Jamaica. I think they had pretty interesting lives, and then got totally boring as soon as I was born.”

When she was in middle school, Dupuis moved with her mother to Connecticut. Much of her extracurricular time as a teenager was spent rehearsing with a semi-professional classical children’s choir that performed everything from Haydn to 19th century Russian music to Serbian folk songs. Dupuis spent many an afternoon poring over sheet music riddled with convoluted countermelodies and maddening dissonances. If nothing else, it left her with a healthy appreciation for strange and eerie harmonies. Later, that taste would reemerge, along with a love for Top 40’s emphatic charm, in the music of Speedy Ortiz.

Dupuis entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2006 with the original intention of studying math, then transferred to Barnard College in New York City, where she majored in creative writing. She freelanced briefly as a music journalist and editor before enrolling in a poetry MFA program at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Dupuis was in grad school when Speedy Ortiz released their first studio album, “Major Arcana,” in 2013. In another life, she would probably have become a poet.

Before Speedy Ortiz, there was Quilty. Dupuis founded the band as a freshman in college, and the project morphed into a collaboration with her then-boyfriend, Julian Fader, a drummer. Together they produced moody, slightly experimental bedroom demos and posted them on the Internet. The band went through many phases—at one point they had a trombone player—though their only full-length album, 2010’s “Clover/Coriander,” has a ‘90s alt-rock bent. Dupuis’s taste for minor keys, fuzzy guitars, and tricky phrasing is nevertheless apparent. She did a majority of Quilty’s songwriting, while Fader took charge of the production. “It was definitely a serious collaboration. It was fun,” says Fader, a Brooklyn-based engineer and member of the soul-pop band Ava Luna. “I remember one time just sitting in our practice space, and in one rehearsal, we sort of sketched out the entire album and by the end of the rehearsal we had a concept for this whole album. It was crazy. I could never have done that by myself.”

Back then, Dupuis and Fader were working at a creative arts summer camp where they had met as campers. Often, she would give herself the same assignments as the kids—write a song around a certain theme, like love, or with a particular chord progression. A lot of her early material was composed this way, the result of an exercise, a novelty.

All that changed when she and Fader broke up in 2011. Suddenly, Dupuis found herself writing in a far more personal vein than she ever had before. “I think when that relationship deteriorated and that band broke up, I suddenly had really bad sh-t to process and I, you know—that was my best friend who I had lived with, and spent every day with, for five years, and I couldn’t talk to him anymore.”

The name “Speedy Ortiz” was borrowed from Jaime Hernandez’s punk-inflected stories in the long-running “Love & Rockets” comic book series. “The character that Speedy Ortiz is named after is a brother of one of the main characters,” Dupuis explains. “He dies through sort of devious circumstances. And then the next bunch of issues [depict] these amazing ways in which all of these characters are dealing with grief. And when I first started making demos for this band I was rereading ‘Love and Rockets,’ and ... my roommate had passed away of a heart attack super young, 25, like, in his sleep. And my childhood best friend had overdosed. So I was dealing with these really young deaths and not knowing how to cope, and watching all these other characters: one of them moves far away, one of them goes on tour. I was just like, ‘Oh, I can kind of relate,’ not so much to the character Speedy Ortiz, but to how everybody else deals with his loss. And that is sort of what the songs were for me in the beginning.”

It was a “weird year,” says Dupuis. She was newly enrolled at UMass, alone in an unfamiliar town, and plunged in grief. But the death of her roommate, a photographer and poet, seemed only to speed her musical output. “I think after James died I kind of wanted to be more engaged and work harder,” she says. “The big takeaway from that was, you can be a totally healthy young person and then your time is up for no apparent reason.”

The first Speedy Ortiz demo, which has since been removed from the band’s website, sounded nothing like the music they make now. “The Death of Speedy Ortiz,” from 2011, was essentially a solo home recording project, with banjo, cello and timpani counted among its eccentric cast of instruments. Dupuis quickly realized that if she wanted to perform the material live she would need to simplify things: “It was either going to be an Arcade Fire deal with too many people, and I kind of hate that look, or just rearrange them to be kind of stripped down.” The lineup eventually coalesced around drummer Mike Falcone, bassist Darl Ferm, and guitarist Matt Robidoux. It didn’t take long for Speedy Ortiz to get noticed. The band’s 2013 full-length studio debut, “Major Arcana,” earned them a review in Rolling Stone and the rarified indie-rock honor of Pitchfork’s “Best New Music.” After that, they hit the road in earnest.

"Sad to say s.o. guitarist [Matt Robidoux] @riddentemple is on an indefinite hiatus," Dupuis tweeted on the morning of May 6, 2014. "Meantime, check his new band pony bones, who slay http://bonypones.bandcamp.com.”

Robidoux followed minutes later with his own Tweet: "After almost 3 years of amazing times I'll be taking an indefinite hiatus from Speedy Ortiz. thank you for everything! See u on the street."

The rollout of the news may have been diplomatic, but it hinted at brewing tensions. The band had just come off of a long, exhausting tour in Europe and the States. Falcone remembers that Robidoux didn’t seem happy during that trip. “It just felt like it didn’t fit,” he says. “And it was kind of a mutual thing. I don’t think any of us wanted to admit it at the time, because we all really wanted to keep it as it was. And I don’t think any of us wanted to say it out loud until we got home from that really long tour.”

“He was used to fronting his own band and really was somewhat imposing with his views of what we should be doing and what it should sound like,” Dupuis says of Robidoux. “And if I disagreed, I was, you know, being dictatorial, instead of just, like, a writer.”

Robidoux saw it differently. “It has always [been] said we were born of a solo project, of Sadie's demos, which is true, but when we spent years touring the country together through basements for no money and were active participants in the Massachusetts scene, it was a real band,” he wrote in an email. “To see this band camaraderie disappear in favor of the monolith of the solo artist was painful to me, mostly because we agreed not to let that happen.”

Since Robidoux’s departure, Dupuis says she has become more assertive of her vision for her songs. “If I write a song, I hear all of the parts at once when I’m thinking it up in the first place,” she explains. “So I have a sense of how the whole thing will sound. And on this album I felt a little more comfortable, and I think my bandmates are more comfortable, too, with knowing that if I’m writing a song, I hear how the drums should be and what the bass part is. So I’ll come to them with fairly fleshed-out ideas for what I’d like them to do. And then they’re all amazing musicians [and] they’re comfortable making changes, and I’m cool accepting that.”

Speedy Ortiz guitarist Devin McKnight, who stepped into Robidoux’s spot after he left the band, calls learning Dupuis’s songs “an exercise of trying to add your own character,” and says that the clarity of her vision has certain artistic advantages over its alternative. “Sometimes it’s hard to get a clear aesthetic from a band if there are a lot of cooks in the kitchen.”

McKnight’s particular contributions can be tough to tease out in the music—his role consists mainly of filling in the space between Dupuis’s own intricate guitar parts, and providing the occasional solo, eloquently distorted—although Dupuis says that she admires his playing so much that she tries to imitate it. Falcone is a loose and expressive drummer, the kind who seems to be holding back even when he is driving. Bassist Darl Ferm is a stealthy, insistent presence, employing a dark, sludgy tone that oozes into its surroundings. (He also provided a number of guitar parts on “Foil Deer.”)

Speedy Ortiz practices in a vast warehouse in Allston, where the muffled cacophony from neighboring rehearsal rooms bleeds through stark white walls adorned with images of rock stars whose pedigrees place them far above such mundane milieu, and the air smells faintly of weed. On the evening of my mid-March meeting with Dupuis, the band convened for a rehearsal in preparation for their performances at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas.

Dupuis describes Speedy Ortiz’s current incarnation as low-key: “Touring is so easy. I didn’t know it could be that easy.” At rehearsal, they display an almost wordless rapport. The practice room is heaped with guitar cases and amplifiers and drum kits arranged higgledy-piggledy. A Budweiser box skulks in the corner. There is a long, aimless preamble while Falcone sets up his drums. “I don’t know how to do this guy,” says Ferm, fiddling with an amp. McKnight replaces a string. We can hear the band next door. Dupuis begins to noodle along, her fingers chasing the chords absentmindedly up the fingerboard.

“There’s a part I want to figure out in ‘Dead Girl,’” she says. She doesn’t bother to sing, since the focus is on the guitars, and they try it out, Dupuis and McKnight slithering in parallel melodies. They stop, try it again.

The band’s main task is to make sure that they can execute the arrangements on “Foil Deer,” since they haven’t had many chances to perform the material live. Dupuis is still monkeying with her parts, honing in on small details. “I want to put a different melody in there,” she says at one point. The session has a calm, collaborative quality, but it is equally clear that Dupuis has no problem speaking her mind, prodding at weak points, pushing for something better.

“Foil Deer” was recorded in three weeks at the Rare Book Room in Brooklyn with producer Nicolas Vernhes, known for his work with Deerhunter. “It’s our best-sounding record,” says Falcone. “Major Arcana” was done on the cheap, but with “Foil Deer,” Speedy Ortiz were afforded the luxury of numerous takes, of tinkering and experimentation. Dupuis says she was at last able to capture the songs as she envisioned them: the extra keyboard parts, the vocal harmonies. It was the also the first time the band recorded to a click track, which may seem inconsequential (or just boring), but it was crucial in helping them stay deliberately mid-tempo. “Major Arcana” is almost frantic by comparison. “Foil Deer” has a swaggering, confident quality, like a villain strolling menacingly into frame in the tense moments before chaos erupts. It is muscular, weightier, and it leaves a more permanent mark.

Not long after the band’s appearance at South by Southwest, Dupuis and I reconvene at the coffee shop. It is overcast and chilly, the seasons seeming to skitter frantically in reverse. I ask Dupuis if she can identify the moment when she realized that her songwriting needed to take a different turn on “Foil Deer.” How did she know that it was time to make an album about “cutting out bullsh-t and taking care of yourself?”

“There were so many sh-tty people the past year who ... we worked with who were sexually inappropriate,” she says.

“I’d hang out with friends and they’d have the exact same stories,” she remarks some time later. “And nobody wants to talk about it because they don’t want to come out as a victim, but I don’t feel victimized. I feel I have a responsibility to call out this kind of behavior so that my friends and people like my friends know, hey, this sh-t happens to everyone. It’s unfortunately a reality of being woman even though we’ve made all these other strides. And what’s left to do is to call it out and not put up with it. So any of the love songs on this album are not really about love. They’re about taking care of yourself.”

Eventually our conversation winds its way to pop music, a favorite topic. Dupuis expresses her admiration for the Charli XCX song “Body of My Own,” a salacious bubble-gum feminist anthem: “Yeah I can do it better when I’m all alone/ Lights out, so high/ All alone/ I got a body of my own.”

Dupuis’s own lyrics are rarely so blunt. She is a devotee of wordplay, of double and triple meanings, of private significances that reveal themselves slyly between entendres. It’s not surprising that she claims more of a kinship with rap’s knotty wit than the bald confessionalism of a lot of indie rock. Her lyrics, she says, must always read well on the page—few sentence fragments, no nonsense. You could spend hours, days, parsing her poetry, following a metaphor as it transmutes. “Everybody’s getting wasted. I just pick my teeth/ Lurking in the shadows of the party lights,” Dupuis sings on “Ginger.” “I wanna fold up/ And fall inside/ The interstitials/ Of killing time/ Wasted/ Wasted, like you.” But time passes differently in Speedy-Ortiz-land: a swerving seven-count, a giddy triple-time. As clearly as she’ll tell you in person what she’s about, Dupuis says so much more in her songs, all at once, strangely and complexly and loudly.

Which is why the strident, exultant chorus in “Raising the Skate”—“I’m not bossy, I’m the boss”—stands out. The phrase is lifted directly from a LeanIn.org video, in which celebrities like Beyoncé and Jennifer Garner endorse a campaign to ban the use of “bossy” as an insult against confident, ambitious young women. It’s not as though Dupuis has never referenced popular culture in her music before—the first Speedy Ortiz EP contained a song titled “Taylor Swift”—but the “bossy” allusion is nevertheless surprising because she tends to write in a more personal vernacular. And indeed, throughout “Foil Deer” Dupuis hews mostly to her usual lyrical style: oblique, interior, evocative. When the claws of the outside world do manage to pierce through, she doesn’t flinch or shrug them off. She just sharpens her own.