Advertisement

Harvard Film Archive Reminds Us That 'Saturday Night Fever' Is More Than A Dance Contest

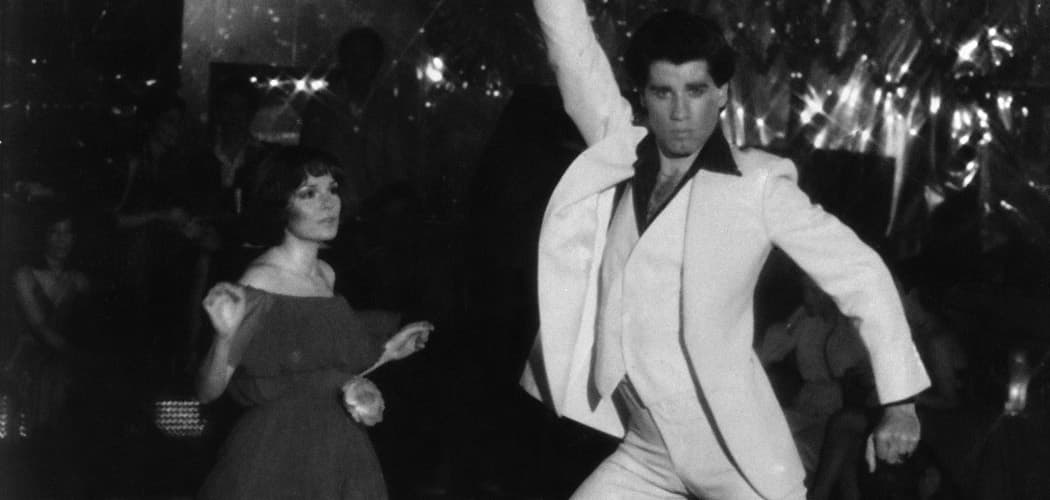

The white suit, that lighted dance floor, the strut — so many tropes from “Saturday Night Fever” have been so tirelessly parodied over the years, becoming such part and parcel of our shared pop iconography that I’ve noticed a lot folks tend to just assume they’ve seen the movie at some point or another, if only through cultural osmosis. Here’s a good way to tell for sure: If you’re laughing derisively about it, you probably haven’t watched “Saturday Night Fever” recently.

This is one tough picture — bristling and raw, with an aggression more attuned to angry-young-man British kitchen sink dramas than Hollywood’s quickie music-fad cash-ins. That’s why “Saturday Night Fever” is screening Monday, Sept. 21 at the Harvard Film Archive as part of guest programmer Athina Rachel Tsangari’s “Furiouser and Furiouser” series, which chronicles some of 1970’s cinema’s harshest outliers. 1977’s unlikely blockbuster will be shown alongside Paul Schrader’s “Blue Collar,” Robert Downey Sr.’s “Greaser’s Palace,” and even Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.” Good company for Tony Manero, crazy as that may sound.

And “crazy” is a polite word for the way folks in Hollywood described theater and record industry impresario Robert Stigwood when he signed “Welcome Back, Kotter’s” Vinnie Barbarino to a million dollar, three-movie contract. It was an era when the carefully segregated worlds of film and television forbid sitcom stars from making the leap to the big screen, but having already auditioned him for the title role in “Jesus Christ Superstar” some five years earlier, Stigwood insisted this John Travolta kid had something special.

The original plan was for Travolta to first star in a movie adaptation of “Grease,” but contractual obligations specified that they couldn’t start filming until 1978, as not to cut into the still-booming Broadway ticket sales. So in the meantime, the producer snapped up the rights to a head-turning New York Magazine cover story, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night.”

Penned by rock critic Nik Cohn, the impressionistic New Journalism piece painted an evocative picture of how this predominantly black and gay disco craze had recently caught on with Italian-American tough guys in the working-class Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn. His story began with the promise: “Everything described in this article is factual and was either witnessed by me or told to me directly by the people involved.” Twenty years later, Cohn admitted that he made most of it up.

“Tribal Rites” is a grim read, with violent, ill-tempered king of the dance floor Vincent a far cry from Tony Manero. It’s also not much of a story. For that, Stigwood turned to screenwriter Norman Wexler. A native of New Bedford and one of the '70s unsung celluloid heroes, Wexler penned outrageous provocations like “Joe” and “Mandingo” while scoring an Oscar nomination for his “Serpico” screenplay. Hollywood’s go-to rewrite guy for “street dialogue,” he was also a dangerously ill manic-depressive, once arrested and escorted off a plane for threatening to kill Richard Nixon.

Comedian Bob Zmuda worked as Wexler’s personal assistant for an entire two weeks, and has spoken extensively about the writer’s penchant for strolling into rough neighborhoods and picking fights, always with a tape recorder rolling. The lines that were shouted during ensuing melees often made their way into the movies. (Zmuda sometimes likes to claim that he and Andy Kaufman’s louche, insult-hurling “Tony Clifton” character was inspired by Wexler.)

However it was obtained, the dialogue in “Saturday Night Fever” is acrid, filthy and altogether unthinkable in today’s political climate. According to Hollywood legend, it was the first major studio release to use the term “blow job,” and director John Badham brags on the DVD commentary that the relentless vulgarity got him fired from his next gig after executives finally screened the picture. (When “Saturday Night Fever” was re-released in a PG version to appeal to a wider audience in 1979, 121 edits were required to obtain the more kid-friendly rating.)

Travolta’s 19-year-old Tony Manero and his claque of go-nowhere friends live at home with their parents, work dead-end jobs and, every Saturday night, spend all their money trying to score with girls at the tacky 2001 Odyssey disco. They’re thoughtlessly racist and downright horrible to women. The only respite is when Tony hits the dance floor, his boorishness redeemed by grace, and this scummy, druggy scene is elevated briefly to nirvana before Sunday morning’s inevitable hangover kicks in.

“You can be a nice girl, or you can be a dame,” explains Harvey Keitel in Martin Scorsese’s 1967 debut feature “Who’s That Knocking at My Door.” The line gets an unprintable update in “Saturday Night Fever,” summing up Tony’s textbook Madonna-whore complex and his bafflement when he encounters the pricelessly named Stephanie Mangano (Karen Lynn Gorney) kicking up her heels on that lighted 2001 Odyssey floor.

The slender thread of a plot follows Tony’s attempts to woo Stephanie into being his partner in a local dance contest, but she’s outgrown guys like him. Moving to Manhattan and taking night classes, Stephanie is trying to better herself and it is very much to the credit of Wexler’s script that she’s stumbling every step of the way. Still, Tony sees her not just as a dance partner but also as possibly his way out of his increasingly claustrophobic neighborhood’s conscripted rituals. It’s no accident they end up dancing to The Bee Gees’ “More Than a Woman,” because Stephanie’s more than a [dame] to Tony, she’s a life raft.

One of the things that makes “Saturday Night Fever” so bruising is that despite considerable charm and a good heart, Tony Manero consistently fails to rise to the occasion. His yearning for something more is always palpable in Travolta’s impossibly endearing performance, but the character is hamstrung by deeply ingrained, stupid macho codes of behavior. By the final reel that dumb dance contest has become an afterthought, and the film goes on spiraling into one shocking scene after another, complete with a suicide and a gang rape — nothing you’d expect from the kitschy reputation. The movie ends on a note of hesitant uncertainty. We don’t know if these kids are gonna make it through, but you really hope they will.

It almost wasn’t that way, as original director John G. Avildsen showed up for work immediately aiming to soften the Tony character and smooth out all of Wexler’s rough edges. After much discussion, an accident of timing put Stigwood in the awkward position of informing Avildsen that he had just been nominated for an Academy Award for his recently released “Rocky,” and also that he was fired from “Saturday Night Fever.” Badham took over the project a scant couple weeks before shooting began.

It’s tough to blame Avildsen for trying to tone down Tony’s crassness, as on paper the character is practically a monster. But the director wasn’t accounting for the unexpected magnetism and sweetness Travolta brought to this misguided soul, in a lightning-in-a-bottle performance I personally consider every bit the equal of James Dean in “Rebel Without a Cause.” Writing in “The New Yorker,” Pauline Kael enthused: “He expresses shades of emotion that aren’t set down in scripts, and he knows how to show us the decency and intelligence under Tony’s uncouthness … He isn’t just a good actor, he’s a generous-hearted actor.” I still dutifully go see every lousy Travolta picture hoping he will someday do this again.

Of course we cannot discuss critical response to “Saturday Night Fever” without mentioning the late Gene Siskel, who reportedly went to see the movie at least 17 times and paid an exorbitant amount of money to buy Travolta’s famous white suit at a charity auction.

“Movies sometimes complete the unfinished corners of our lives,” wrote Siskel’s longtime sparring partner Roger Ebert in a beautiful remembrance, “We all have a powerful memory of the person we were at that moment when we formed a vision for our lives. Tony Manero stands poised precisely at that moment. He makes mistakes, he fumbles, he says the wrong things, but when he does what he loves he feels a special grace.”

Those transporting moments of grace are probably why “Saturday Night Fever” made Marvel money at the box office back in 1977. The uncompromising grit surrounding them are why we’re still talking about it today. Again, this is one tough picture.

Over the past 16 years, Sean Burns’ reviews, interviews and essays have appeared in Philadelphia Weekly, The Improper Bostonian, Metro, The Boston Herald, Nashville Scene, Time Out New York, Philadelphia City Paper and RogerEbert.com. He stashes them all at splicedpersonality.com.