Advertisement

New Exhibit Explains How Isabella Stewart Gardner Amassed Her Famous Art Collection

Isabella Stewart Gardner — the astute art collector and artist patron — is famous for stipulating that her trove of masterpieces remain exactly where she hung them in her historic Boston museum.

But parts of her singular collection have been on the move recently for a first-of-its-kind exhibition titled "Off the Wall," which tells the origin story of the collection itself.

A Painting Worth Following

The museum's professional art handlers gently remove an eye-popping 15th century painting from its place on the wall. It’s Italian master Botticelli’s, "The Tragedy of Lucretia."

"Watching it get lifted up off the wall and then taken down is really one of the more nerve-wracking moments for me," Christina Nielsen admitted as she looked on, "as a curator I often have to avert my gaze."

Nielsen relaxes a bit as Botticelli’s masterpiece is secured to a cart that will move it from Gardner’s historic palace to the museum’s new contemporary wing. It will join about 25 other works in the new "Off the Wall" exhibition. It's a creative way to keep highlights from Gardner’s collection in the public view while the roof above their usual location is repaired.

"We are not a museum that’s used to moving the collection around very much," Nielsen told me as we followed the masterwork down the corridor. "And you see they’re putting the Botticelli into our passenger elevator -- which is not really meant for art handling because the collection doesn’t really move," she explained.

Gardner stated in her will that her collection and museum remain as she left them, which has caused legal issues since her death in 1924.

"In this case — bringing 25 works out of the palace and into the new building — we sought permission from the attorney general and were given it," Nielsen recalled, "because it’s part of preserving her vision forever."

Advertisement

That vision is the focus of this new exhibition. Nielsen selected the 25 works to tell the story of how Gardner amassed her stellar art collection. The curator said visitors always ask questions about how the socialite, philanthropist and art patron managed to pull it off.

"'How much did it cost? How did she buy this? How’d she get her money?' So again, these are valid questions, and really interesting ones," Nielsen said.

This new exhibition provides answers.

How Did Mrs. Gardner Do It?

On the ground floor of the original building you can find rarely seen sales receipts, letters and other materials from Gardner’s extensive archive. They're in a funky, little room adjacent to her office that she dubbed, "the Vatichino." (Apparently she made up the word that curators say could mean, "Little Vatican.")

In the '70s the space was converted into a coat room. But it's been reclaimed after the new, Renzo Piano-designed building went up.

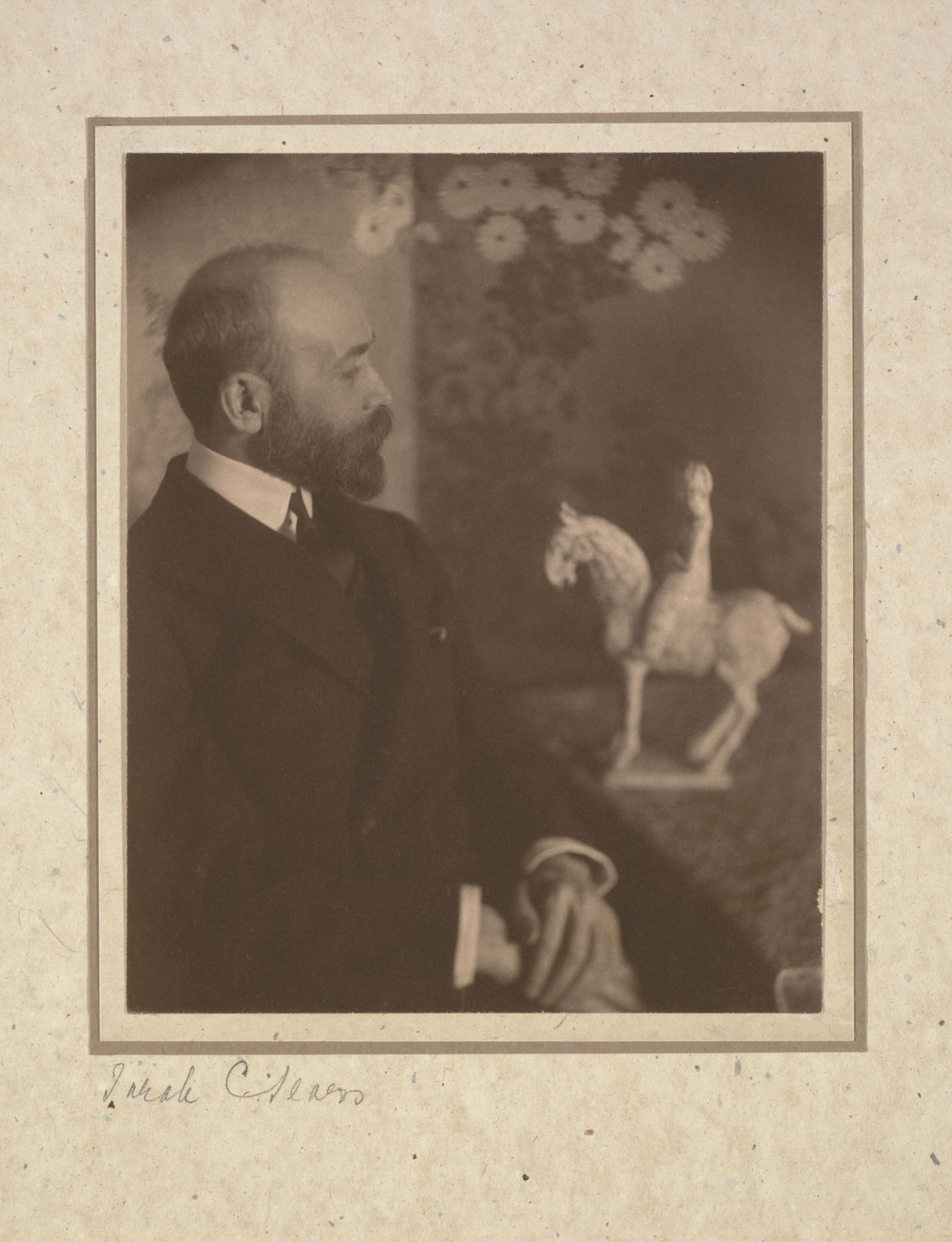

Visitors can peruse photographs of and from Gardner’s art dealers, fellow activists and artist she championed, like John Singer Sargent. A record album of Flamenco music he gave his patron as a gift rests under glass.

Co-curator Casey Riley assembled the Vatichino display and listed off Gardner's constellation of friends.

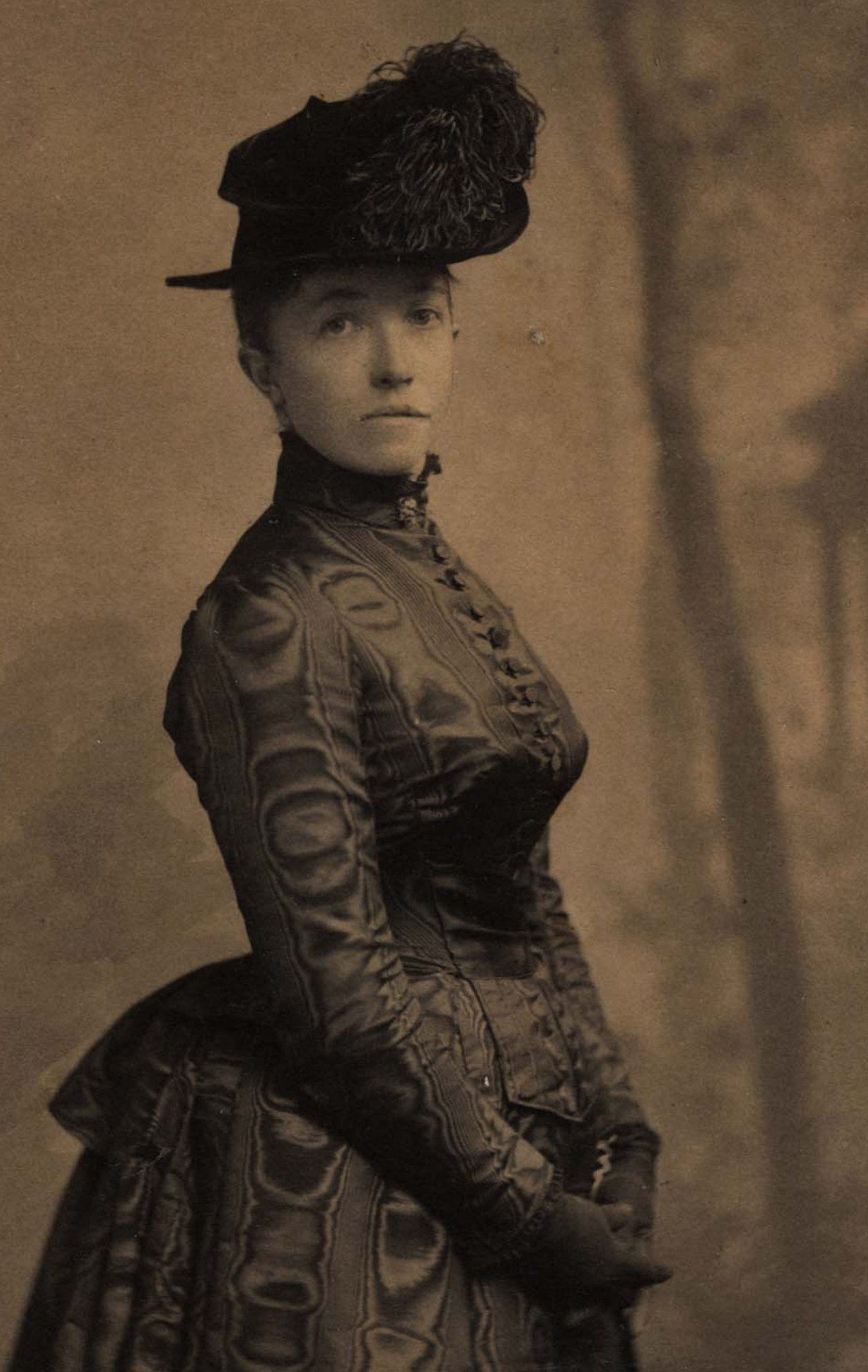

"There’s Sarah Bernhardt, there’s Ellen Terry, the Shakespearean actor. This is Nellie Melba, the operatic singer from Australia -- she actually sang on the steps of the Dutch Room," Riley told me.

"She collected exceptional people the way she collected exceptional works of art," said Peggy Fogelman, the museum's new director.

"She was the original social networker and she surrounded herself with influencers," Fogelman continued. "And they all believed in her, in the amazing museum she was going to build, and in her mission to bring art to the American public."

For Gardner, Nielsen said, the transcendent power of art was what the young, industrializing (sometimes soul-less) America needed.

"You really begin to see the museum itself and the collection very differently as part of a really broad pursuit," Nielsen said.

Charting Gardner's Pursuit Of Art

So how did Gardner's hot pursuit begin? According to Nielsen, it started in earnest at a Paris auction house in 1892.

"The first really serious thing is 'The Concert' by Vermeer," she said.

Gardner would've been up against well-heeled families like the Fricks, the Morgans and the Hearsts. And, unlike most other art buyers and collectors at the time, Gardner was a woman.

"She has a man bid on her behalf," Nielsen said, recalling the story. "She sits in the back of the room, and she’s got a handkerchief over her face. Her main competitors were the National Gallery in London and the Louvre that day," Nielsen went on. "And they realized they were bidding against each other — so they did a sort of gentlemanly bowing out. Meanwhile her agent swooped in and bought the picture and suddenly Isabella Stewart Gardner was a well-known name in the art world overnight."

Tragically, Vermeer’s "The Concert" is one of the 13 works stolen from the museum in 1990. A small reproduction takes its place in the exhibition.

After the Vermeer, Gardner and her husband, Jack, continued to buy more Dutch art, which was in vogue, with money she inherited from her family. Their next major score was a self-portrait by Rembrandt.

In the exhibition you can stare right into the young, rising artist's eyes. But works from the Italian Renaissance became Gardner's true passion. That’s where the Botticelli we were following earlier comes in.

"She wanted a Botticelli," Nielsen said. "What we know about her collecting was there were a couple of different criteria that she had. One was that these masterpieces should be by the hand of a master. Well, Botticelli? You can tick that box."

Gardner also wanted works that had an impressive ownership history and delivered great visual impact. Botticelli’s "Tragedy of Lucretia" had both. Plus there were no other works by Botticelli yet in America.

The man who found the dramatic painting for Gardner knew what she liked. Bernard Berenson, a Lithuanian Jewish immigrant who studied at Harvard, was an influential art historian and an art buyer for Gardner. They had a close but complicated relationship.

Gardner curator Nathaniel Silver read me a letter Berenson wrote to Gardner in 1894:

"How much do you want a Botticelli? Lord Ashburnham has a great one. One of the greatest. A Death of Lucretia. Although the noble lord is not keen on selling it, a handsome offer would not insult him. I should think about 3,000 pounds should be about right."

'For The Education And Enjoyment Of The Public Forever'

Today Nielsen says the Botticelli purchase would’ve been about $440,000. The exhibition’s gallery labels include the prices Gardner paid, which is not usually revealed in the museum world. The list of Gardner’s major "gets" goes on, and each work has its own story to tell.

If you've been to the Gardner you know they usually hang in the historic building’s ornate, dimly lit rooms, sometimes high up on the walls (in the case of Piero della Francesca's "Hercules" (1470). Now in the state-of-the-art, contemporary gallery setting, curator Christina Nielsen says we can see them in a new light.

"Being able to be close to them, and being able to see them lit to their best advantage, it’s like looking over the shoulders of the artists," she mused. "So you notice details on these paintings that you wouldn’t ever have seen before — even if, like me, you pass by them every day."

In 1903, a few years after her husband’s death, Gardner finally realized her dream of opening her palace museum. When she died 20 years later, Gardner left her legacy in trust — “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever.”

The "Off the Wall" exhibition runs through Aug. 15, and then Gardner’s masterpieces will return to their familiar spots in her palazzo.

Correction: Gardner's first bid at a Paris auction house was in 1892, not 1982. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on March 16, 2016.