Advertisement

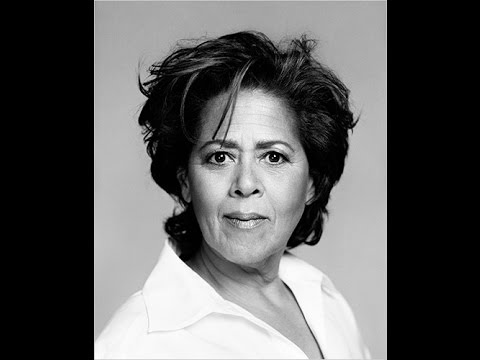

Tony-Nominated Anna Deavere Smith Ably Embodies Those On Front Lines Of School-To-Prison Pipeline

Tony-nominated performer/playwright/professor Anna Deavere Smith includes a “second act” in her new theater piece “Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education,” that is a sort of discussion group. This may seem redundant, since the artist herself is a one-woman discussion group.

Smith’s award-winning documentary dramas, including this latest -- presented by American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) at the Loeb Drama Center through Sept. 17 — are culled from hundreds of verbatim interviews. Interweaving them, the performer, something of a civilly engaged Sybil, represents — and uncannily embodies — a wide range of the folks she’s queried about a given, complicated, troubling issue. “Notes from the Field” homes in on what some call the school-to-prison pipeline: the syndrome in which poor, usually minority youths are disproportionately punished, even in pre-school, then shunted into the juvenile justice system and often into a lifetime of ins and outs at the Big House.

Like “Fires in the Mirror,” Smith’s exploration of the 1991 Crown Heights, Brooklyn riots, and “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” her inquiry into the aftermath of the Rodney King beating, “Notes from the Field” offers a performance of extraordinary emotional and intellectual verisimilitude. In the new work, Smith powerfully channels educators, activists, students, parents, prisoners, politicians, judges, journalists and James Baldwin. But she does not so much mimic her subjects — though she does that with preternatural accuracy — as render them soul, stance, dialect, tics and all. Portraying pummeled freedom rider turned Georgia Congressman John Lewis in all his slow-spoken, Southern, stentorian grace at the end of “Notes from the Field,” she moves you like, well, like John Lewis moves you.

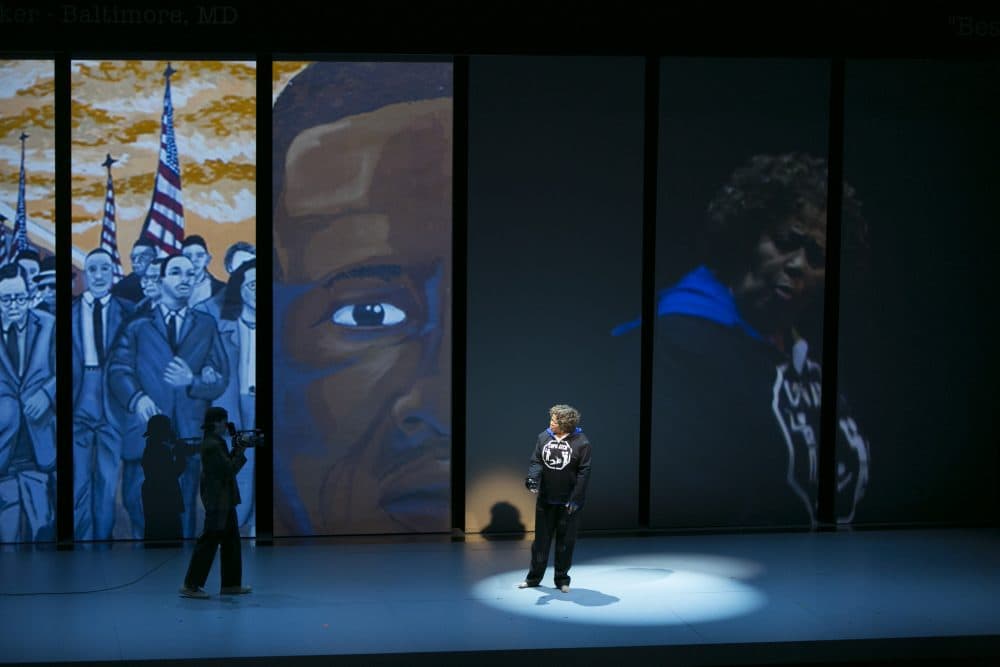

Embodying, in purple robes, with microphone in hand, the pastor Jamal Harrison Bryant, who used the Gospel of Luke to whip up the crowd at Freddie Gray’s funeral, she has the spectators on their feet as if they were there in the congregation. Then, sprawled in a chair with both body and diction hanging loose, she conjures the resigned fury of Allen Bullock, a protestor arrested during the riots that followed Gray’s brutal demise in Baltimore police custody. Telling it like it is about generalized police aggression in his city (which is also Smith’s hometown), Bullock memorably maintains that it’s “not a racist thing; it’s a hatred thing.”

That brings me to “act two,” since that quote from Bullock formed the centerpiece of the facilitated discussion I attended (we are broken down into groups of about 20) before the audience’s return to the playing space for a “coda,” performed by Smith with call-and-response punctuation by San Francisco-based jazz bassist Marcus Shelby (who also provides effective musical embellishment to act one).

Talkbacks, of course, have become de rigueur in the theater. They usually occur at the end of a performance and attendance is voluntary. At some institutions, including the A.R.T., experts in pertinent fields have been engaged to lead these discussions. Here, however, the civil engagement is sandwiched into the performance, with staff-trained facilitators (there are 49 of them listed in the program) guiding chats among strangers still strongly in the grip of both the issue and the performance.

Smith is passionate about these meetings being an integral part of the nearly three-hour “Notes from the Field” experience. As several of the most compelling voices in the piece argue, this school-to-prison trajectory, particularly in underserved, over-policed communities, is an urgent, explosive problem. And Smith hopes this opportunity to talk about it will inspire at least some playgoers to become actively involved in communal efforts to “fix things.” As interviewee Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, suggests, what’s required here is a “massive investment,” tantamount to what we put into our highways, and the window for that investment is now.

Advertisement

As a theatergoer who came for Smith’s profoundly affecting, activism-propelled art, not to share in mild conversation triggered by it, I can’t say that lightning struck during my particular "act two." On the other hand, the consideration of racism, hatred and how to ameliorate them didn’t interrupt the mounting power of Smith’s intricately informed presentation, and it may have beaten eating brownies while lingering in the Loeb lobby. You decide.

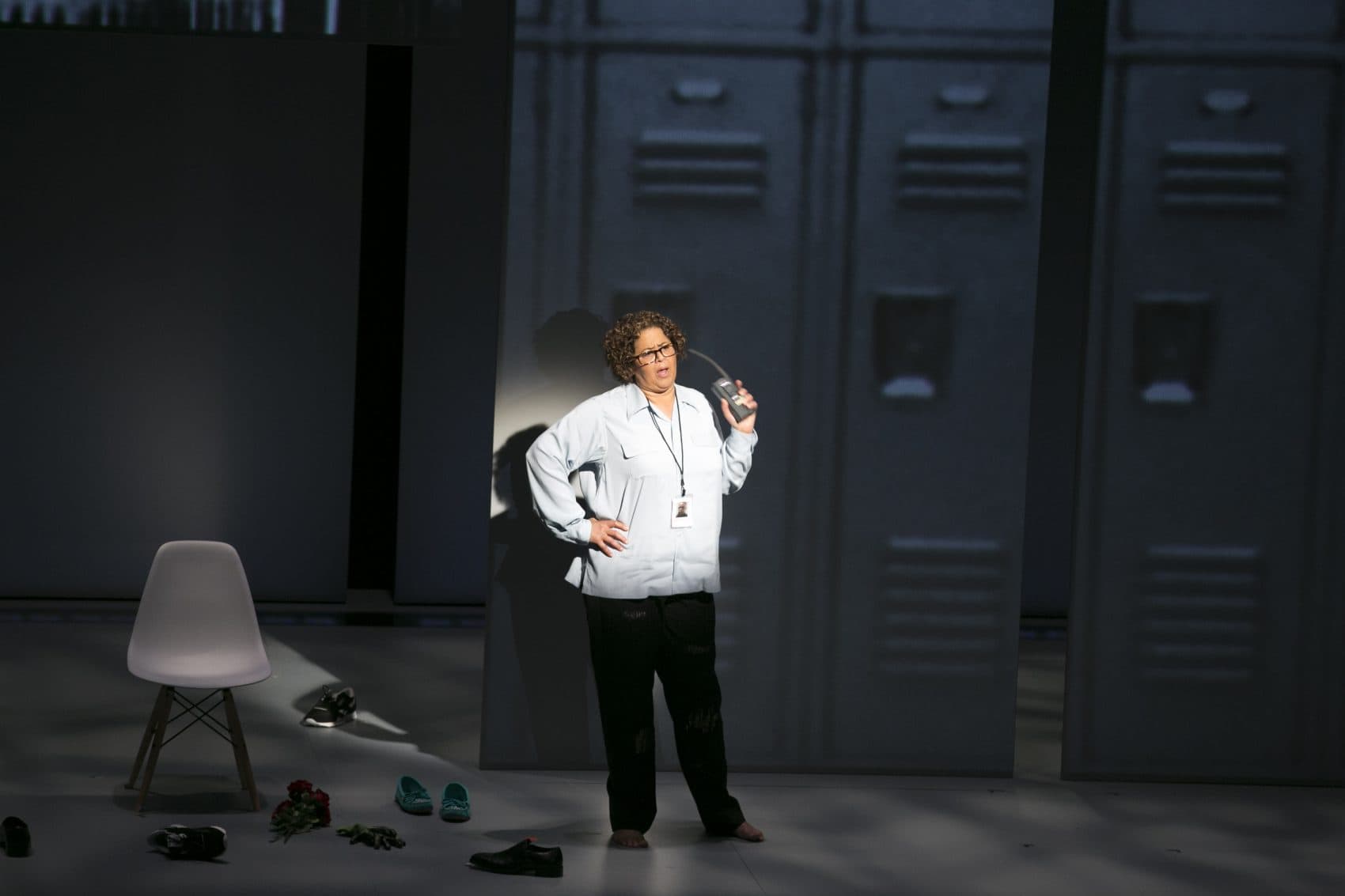

But about the work itself: I have seen three of Smith’s documentary theater pieces (both “Fires in the Mirror” and “Let Me Down Easy,” about our health care system, were performed at A.R.T.) and consider her a scholar and a genius. But “Notes,” directed by Leonard Foglia with a projection design by Elaine McCarthy, is both the busiest and the most cinematic of Smith’s solo works. With its barrage of visual information, the piece mirrors the means as well as the times of its 21st-century subjects, augmenting the performer’s eerily diverse representations of folks on the front lines, both burned out and on fire, with larger-than-life video footage.

For example, Smith morphs into incredulous Baltimore deli worker Kevin Moore, who filmed the police takedown of Freddie Gray on his cellphone, and that footage looms. As Washington-based Emerson Collective journalist Amanda Ripley and appalled student witness Niya Kenny recap “The Shakara Story,” about the Columbia, South Carolina, high-school girl forcibly flipped from her desk by a hulking white policeman for refusing to relinquish her cellphone, we see it go down. “He just threw a whole girl,” Kenny exclaims.

But at the center of the visceral flash and struggle is Smith, whose engagement with this issue is palpable. The artist, 65, comes from Baltimore, from a family of educators in an era when individual educators could matter, and she is not going to take the devolution of that system lying down.

Nor are such fighters as Linda Wayman, principal of Strawberry Mansion High School in Philadelphia, who decries charter schools for selecting the easier students, leaving her with a school population 38 percent of which has special needs and can’t read. Like a number of Smith’s characters (all of whom are, I think, Native American, Hispanic or people of color), Wayman has an inspiring if quirky personal story to tell and an emotionality such that the salvaging of just one child can set her whooping and hollering.

Brilliant though she is, Smith hasn’t got an easy fix for this school-to-prison rent in our society. Not everyone she talked to agrees about its cause or its solution. Dr. Victor Carrion, psychiatrist and director of the Stanford Early Stress Research Program, argues “historical trauma” stretched across generations. Steven Campos, a Disney Hall dishwasher who is a veteran of the O.H. Close Youth Correctional Facility in Stockton, California, calls that “bulls---.”

But Smith’s subjects do shine a light — ably cupped in the performer’s hands — on an immensely distressing problem that stretches from kindergarten suspensions to Black Lives Matter. In even beginning to shape a solution, the operative word — whether it’s lodged in the fiery mouth of Rev. Bryant or in the more beseeching one of Principal Wayman — would seem to be compassion, the operative attitude fervor. And it’s catching.